VITAMIN B12 DEFICIENCY AND DEPRESSION: WHAT IS THE MECHANISM?

Department of Pharmacy, Mentor Pharmaceutical Consulting Private Limited, Melbourne, Australia

*Corresponding Author:

Gregory Russell-Jones, Department of Pharmacy, Mentor Pharmaceutical Consulting Private Limited, Melbourne,

Australia,

Email: russelljonesg@gmail.com

Received: 14-Apr-2022, Manuscript No. AJOPY-22-60815;

Editor assigned: 18-Apr-2022, Pre QC No. AJOPY-22-60815 (PQ);

Reviewed: 28-Apr-2022, QC No. AJOPY-22-60815;

Revised: 02-May-2022, Manuscript No. AJOPY-22-60815 (R);

Published:

07-May-2022, DOI: 10.54615/ 2231-7805.S2.001

Introduction

Depression is a major cause of disability worldwide, affecting not only adults but children and adolescents, and can be associated with an increased rate of suicide in the later population [1-3]. Although the etiology of depression is unclear the most common treatments for depression are the use of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) or Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs) [4]. Vitamin B12 deficiency has been associated with depression in adults, children and the elderly [5-16]. Of note, rates of depression have been found to be higher in vegetarians than omnivores [17,18]. Measurement of vitamin B12 deficiency is controversial and several authors have elected to use elevations in MMA as a marker true functional vitamin B12 deficiency [19]. Hypothyroidism has also been associated with depression in a number of studies with the association being higher in females [20-25]. Whilst the cause of the depression in hypothyroidism has not been established, there is considerable literature linking hypothyroidism and vitamin B12 deficiency with rates of 10%-40% of vitamin B12 deficiency in hypothyroid patients, as measured by absolute levels in serum, however, studies looking at hypothyroidism and functional vitamin B12 deficiency are scarce [26-29]. A direct relationship has been found between levels of TSH and homocysteine, which was not, related to serum B12 levels, hence functional B12 deficiency rather than absolute B12 deficiency was related to TSH status [30-32]. Measurement of serum vitamin B12 does not give an accurate assessment of the functional activity or not of the vitamin B12 [33-35], and hence markers such as MMA and Homocysteine can be used to determine if there is a functional sufficiency or deficiency of vitamin B12. Given the apparent linkage between low absolute levels of vitamin B12 and elevated homocysteine, hypothyroidism, and the potential role of altered serotonin metabolism in depression, a study was conduction in which vitamin B12 status, as determined by MMA was compared to functional vitamin B2 deficiency as assessed using glutaric acid as well as the tryptophan metabolites Quinolinic Acid(QA) and Kynurenic Acid(KA) and the serotonin metabolite 5-Hydroxyindole-Acetic Acid (5HIAA).

Materials and Methods

Study sample

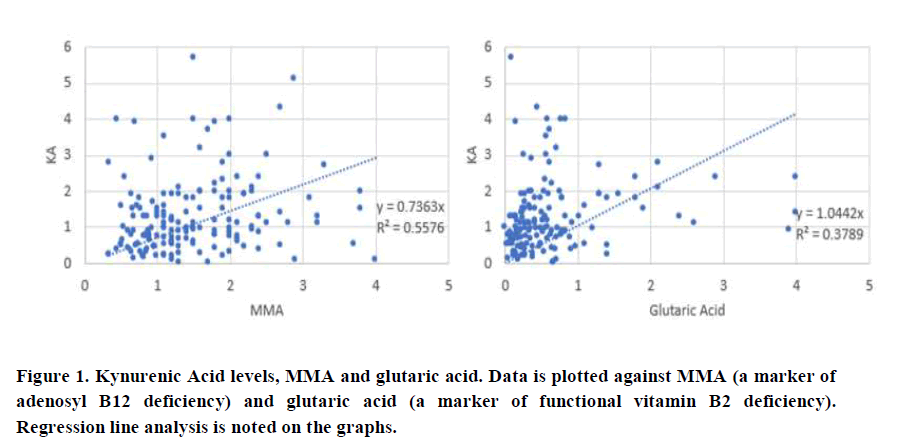

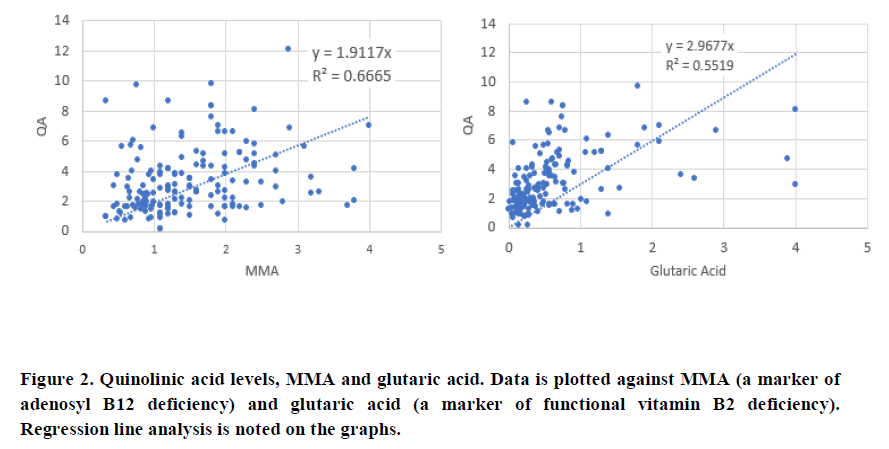

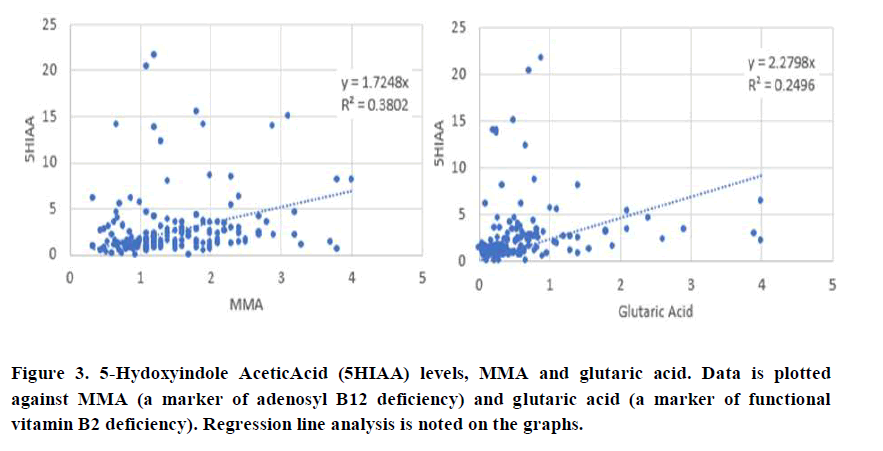

A retrospective analysis was performed upon data submitted to us for analysis from a cohort of 350 children and adults who had submitted their Organic Acids Test data (Great Plains Laboratories, Lenexa, KS, USA) for analysis and who had also supplied their serum vitamin B12 levels. Subjects were from a range of countries including USA, Canada, United Kingdom, Ireland, Germany, Spain, France, Italy, Bulgaria, India, Sweden, Bulgaria, Serbia, Dubai, Croatia and Australia. Age distribution of the 350 individuals was 1-5 (30); 6-10 (30); 11-15 (40); 16-20 (19); >21 (216). No selection was made in the acceptance of data, with no data being rejected. Individual data is plotted as Scattergrams (Figures 1-3). Data is represented as mmol/mol creatine for NT.

Results and Discussion

The neurotransmitter metabolites Kynurenic Acid (KA), Quinolinic Acid (QA) and 5-Hydroxyindole Acetic Acid (5HIAA) were compared to the known marker of vitamin B12 deficiency, Methylmalonic Acid (MMA). In addition, KA, QA, and 5HIAA were also compared to urinary glutaric acid levels, a known marker of functional B2 deficiency.

There was a good correlation between QA and MMA (0.665) and QA and glutaric acid (0.5519), which was slightly better than the correlation which was slightly better than the correlation between KA and MMA (0.557) and KA and glutaric acid (0.379). Of note, there was a significant deviation from the line of best fit, when glutaric acid levels dropped below 1.0, at which time; levels of KA were much higher than when glutaric acid was above 1.0. Comparison of 5HIAA with MMA (Figure 3), showed a lower correlation co-efficient (0.382), which was further reduced when 5HIAA was plotted against glutaric acid (R2=0.2496). There was also a significant deviation from the line of best fit when glutaric acid levels were less than 1.0.

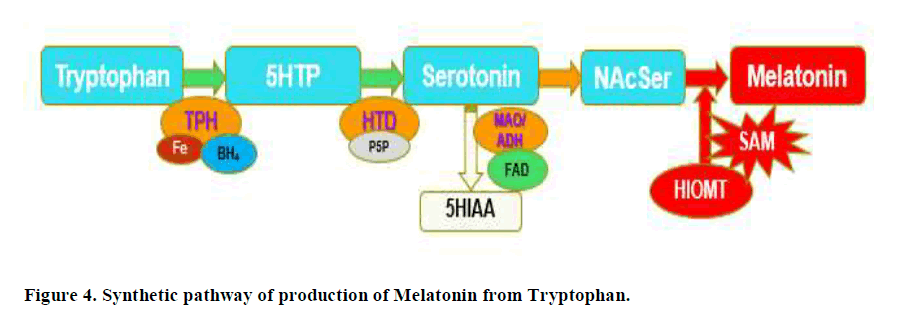

Production of serotonin Figure 4, is critically dependent upon the action of the enzyme Tryptophan-5-Hydroxylase (TPH), followed by the subsequent reaction of the PLP dependent enzyme, Hydroxy-Tryptophan Decarboxylase (HTD). Serotonin is subsequently acetylated to form N-Acetyl Serotonin (NAcSer), which is then methylated by the S-Adenosylmethionine (SAM), as the methyl donor, by the action of Hydroxyindole-O-Methyl Transferase (HIOMT). In vitamin B12 deficiency, the last step in production of Melatonin is blocked due to lack of production of SAM.

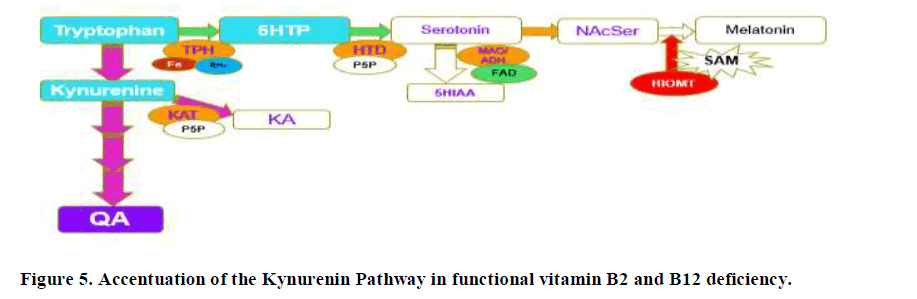

Production of FMN from riboflavin by the enzyme riboflavin kinase is compromised in dietary insufficiency of Iodine and Selenium. In addition, the activation of vitamin B6 to form PLP requires the FMN-dependent enzyme, pyridoxamine phosphate oxidase (Figure 5).

Hence, in deficiency of any of vitamin B2, vitamin B6, Iodine and Selenium, levels of serotonin will be reduced as too will melatonin production, and tryptophan metabolism will favour the Kynurenine pathway, potentially leading to depression due to lower levels of serotonin (Figure 5). In this case QA will be increased, but KA will not be affected as greatly as the enzyme Kynurenine Amino Transferase (KAT) is also PLP dependent. As levels of Iodine, Selenium, B2 and B6 increase, then the reaction will start to favour both production of serotonin and also the conversion of kynurenine to kynurenic acid, as well as the metabolism of fatty acids, with lowering of the levels of glutaric aid. This can be seen in the comparison of KA and Glutaric acid, where when glutaric acid levels drop below 1.0, there is a big increase in the levels of KA. If, however, despite the sufficiency of Iodine and Selenium, there was a deficiency in Molybdenum, the enzyme FAD-synthase, would have reduced ability to produce FAD, from FAD, and so excess Serotonin could not be removed by the FAD-dependent enzyme Monoamine-oxidase. Potentially this would lead to increased levels of serotonin, with subsequent down-regulation of serotonin receptors and this would then also result in depression. In the data, 5HIAA levels are low when glutaric acid is greater than 1.0, suggesting that this is the cut-off value for the activity of MAO. Levels, of 5HIAA had greatly increased up to that point suggesting higher and higher levels of production of serotonin.

Lack of FMN, will also result in functional B2 deficiency and reduced production of both FMN and FAD, the second active form of vitamin B2. Cycling of vitamin B12 requires both FMN and FAD for the enzyme methionine synthase reductase, and FAD for Methylene-tetrahydrofolate reductase, and so in functional B2 deficiency there will also be functional B12 deficiency, particularly for Methyl B12, which is central to the production of the methylation compound S-Adenosylmethionine (SAM). SAM is critical for the conversion of NAcSer to Melatonin, thus, in functional vitamin B12 deficiency, the production of Melatonin is reduced. This in turn would lead to an accumulation of the precursors, serotonin and NA cetyl-serotonin. Overproduction of serotonin would in turn cause depression due to receptor down-regulation of the Serotonin receptors. Clearly, the data would lie somewhere in between the two extremes.

The situation would be somewhat different in absolute vitamin B12 deficiency, as serotonin production and also inactivation of excess serotonin would not be compromised, and further the production of kynurenic acid would also not be compromised. In this situation, depression would result purely from over-production of serotonin with serotonin receptor down-regulation. The data presented is similar to the work of others, in which functional vitamin B12 deficiency, as measured by elevated homocysteine has been associated with depression in many studies [36,37]. Of note, serum levels of vitamin B12, in the subjects studied was 909 pmol/L +/- 578; as such nearly every person assayed would not have been diagnosed with B12 deficiency if serum B12 levels were used.

The corollary to the study is that to effectively treat depression, it would be important to establish the functional sufficiency of the minerals Iodine, Selenium and Molybdenum, as well as functional sufficiency of vitamin B2, vitamin B6 and vitamin B12. Given the interdependence of these minerals and vitamins in maintaining the functional sufficiency of vitamin B12, it would be essential that treatment for depression includes appropriate correction of these essential vitamins and minerals.

Conclusion

Comparison of the urinary organic acid metabolites of the Tryptophan/Serotonin/ Kynurenine pathway with the traditional marker of vitamin B12 deficiency, MMA, and the riboflavin deficiency marker, glutaric acid, has identified three potential mechanisms for the development of depression in functional vitamin B12 deficiency. In absolute vitamin B12 deficiency there is minimal production of melatonin, leading to over-production of serotonin and the serotonin break-down product 5HIAA. In contrast in deficiency of Iodine, Selenium, Molybdenum vitamin B2 and vitamin B6, production of serotonin would be almost non-existent leading to depression due the inability to produce serotonin. An intermediate condition would occur in which deficiency of Molybdenum, alone, would lead to over-production of serotonin, receptor down regulation and resultant depression. Treatment of depression would therefore only be effective if adequate supplementation with Iodine, Selenium, Molybdenum, vitamin B2 and vitamin B6, plus methyl vitamin B12 was achieved.

Declarations

Compliance with ethical standards:

We declare that there are no potential conflicts of interest

Research did not involve human participants and/or animals.

No Informed consent is required, all data is “blinded” and as such is anonymous

Data analysis was carried out under the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council guidelines (NHMRC). Under these guidelines, all data was deidentified and steps were taken to ensure the anonymity and confidentiality of the data. Deidentification has consisted of absolute anonymity and confidentiality of the data, such that no specifics such as gender, ethnicity, Country of Origin, etc is associated with any data point in the study.

As such per the NHMRC guidelines:

The research does not carry any risk to the participants

The benefits of the research are many and will be of considerable benefit to any past, current or future participants, and as such represent no harm.

The data is from over 600 participants collected over 6 years and as such it would be impracticable to obtain consent from the participants. Further the participants had been notified at the time of analysis that data presented for analysis might potentially be used in research -but would be totally de-identified (which it has been).

There is no known reason why any of the participants would not have consented if they had been asked

Given the total de-identification of the data, there is absolute protection of their privacy

Data is only housed in one location and has only been assessed by one person, and as such the confidentiality of the data can be assured. No financial benefits from the data is anticipated, the data will be used to help prevent and treat those to whom the data applies. The waiver is not prohibited by State, Federal or International Law.

References

- Dell'Osso L, Carmassi C, Mucci F, Marazzitiet D. Depression, Serotonin and Tryptophan. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2016; 22(8): 949-954.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- DeFilippis M, Wagner KD. Management of treatment-resistant depression in children and adolescents. Paediatric Drugs. 2014; 16(5): 353-361.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Masi G, Liboni F, Brovedani P. Pharmacotherapy of major depressive disorder in adolescents. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 2010; 11(3): 375-86.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Weller EB, Weller RA. Treatment options in the management of adolescent depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2000; 61(1): 23-28.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sangle P, Sandhu O, Aftab Z, Anthony AT, Khan S. Vitamin B12 Supplementation: Preventing Onset and Improving Prognosis of Depression. Cureus. 2020; 12(10): e11169.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Coppen A, Bolander-Gouaille C. Treatment of depression: time to consider folic acid and vitamin B12. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2005; 19(1): 59-65.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khosravi M, Sotoudeh G, Amini M, Raisi F, Mansoori A, Hosseinzadeh M. The relationship between dietary patterns and depression mediated by serum levels of Folate and vitamin B12. BMC Psychiatry. 2020; 20(1): 63.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saraswathy KN, Ansari SN, Kaur G, Joshi PC, Chandel S. Association of vitamin B12 mediated hyperhomocysteinemia with depression and anxiety disorder: A cross-sectional study among Bhil indigenous population of India. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN. 2019; 30: 199-203.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Petridou ET, Kousoulis AA, Michelakos T, Papathoma P, Dessypris N, Papadopoulos FC, et al. Folate and B12 serum levels in association with depression in the aged: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging&Mental Health. 2016; 20(9): 965-973.

[Crossref][Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stanger O, Fowler B, Piertzik K, Huemer M, Haschke-Becher E, Semmler A, et al. Homocysteine, folate and vitamin B12 in neuropsychiatric diseases: review and treatment recommendations. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 2009; 9(9): 1393-1412.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Esnafoglu E, Ozturan DD. The relationship of severity of depression with homocysteine, folate, vitamin B12, and vitamin D levels in children and adolescents. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2020; 25(4): 249-255.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim JM, Stewart R, Kim SW, Yang SJ, Shin IS, Yoon JS. Predictive value of folate, vitamin B12 and homocysteine levels in late-life depression. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2008; 192(4): 268-274.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dimopoulos N, Piperi C, Salonicioti A, Psarra V, Gazi F, Papadimitriou A, et al. Correlation of folate, vitamin B12 and homocysteine plasma levels with depression in an elderly Greek population. Clinical Biochemistry. 2007; 40(9-10): 604-608.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tiemeier H, Van Tuijl HR, Hofman A, Meijer J, Kiliaan AJ, Breteler MMB. Vitamin B12, folate, and homocysteine in depression: the Rotterdam Study. The Americal Journal of Psychiatry. 2002; 159(12): 2099-2101.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vogiatzoglou A, Smith AD, Nurk E, Christian A, Per M, Stein E, et al. Cognitive function in an elderly population: interaction between vitamin B12 status, depression, and apolipoprotein E ε4: the Hordaland Homocysteine Study. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2013; 75(1): 20-29.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wolters M, Ströhle A, Hahn A. Cobalamin: a critical vitamin in the elderly. Preventive Medicine. 2004; 39(6): 1256-1266.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kapoor A, Baig M, Tunio SA, Memon AS, Karmani H. Neuropsychiatric and neurological problems among Vitamin B12 deficient young vegetarians. Neurosciences (Riyadh). Neurosciences Journal. 2017; 22(3): 228-232.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Berkins S, Schiöth HB, Rukh G. Depression and Vegetarians: Association between Dietary Vitamin B6, B12 and Folate Intake and Global and Subcortical Brain Volumes. Nutrients. 2021; 13(6): 1790.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gültepe M, Ozcan O, Avşar K, Çetin M, Ozdemir AS, Goka M, et al. Urine methylmalonic acid measurements for the assessment of cobalamin deficiency related to neuropsychiatric disorders. Clinical Biochemistry. 2003; 36(4): 275-282.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guimarães JM, de Souza Lopes C, Baima J, Sichieri R. Depression symptoms and hypothyroidism in a population-based study of middle-aged Brazilian women. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009; 117(1-2): 120-123.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Constant EL, Adam S, Seron X, Bruyer R, Sehhers A, Daumerie C. Hypothyroidism and major depression: a common executive dysfunction? Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2006; 28(5): 790-807.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhao S, Chen Z, Wang X, Yao Z, Lu Q. Increased prevalence of subclinical hypothyroidism in female hospitalized patients with depression. Endocrine. 2021; 72(2): 479-485.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Loh HH, Lim LL, Yee A, Loh HS. Association between subclinical hypothyroidism and depression: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2019; 19(1): 12.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zavareh AT, Jomhouri R, Bejestani HS, Arshad M, Daneshmand M, Ziaei H, et al. Depression and Hypothyroidism in a Population-Based Study of Iranian Women. Romanian Journal of Internal Medicine. 2016; 54(4): 217-221.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bode H, Ivens B, Bschor T. Association of Hypothyroidism and Clinical Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021; 78(12): 1375-1383.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tudhope GR, Wilson GM. Deficiency of vitamin B12 in hypothyroidism. The Lancet. 1962; 1(7232): 703-706.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jabbar A, Yawar A, Waseem S, Islam N, Haque NU, Zuberi L, et al. Vitamin B12 deficiency common in primary hypothyroidism. Journal of Pakistan Medical Association. 2008; 58(5): 258-61. Erratum in: Journal of Pakistan Medical Association. 2009; 59(2): 126.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Collins AB, Pawlak R. Prevalence of vitamin B-12 deficiency among patients with thyroid dysfunction. Asian Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2016; 25(2): 221-226.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aon M, Taha S, Mahfouz K, Ibrahim MM, Aounet AH. Vitamin B12 (Cobalamin) Deficiency in Overt and Subclinical Primary Hypothyroidism. Clinical Medicine Insights: Endocrinology and Diabetes. 2022; 15: 11795514221086634.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Catargi B, Parrot-Roulaud F, Cochet C, Ducassou D, Roger P, Tabarin A. Homocysteine, hypothyroidism, and effect of thyroid hormone replacement. Thyroid. 1999; 9(12): 1163-1166.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ozmen B, Ozmen D, Parildar Z, Mutaf I, Turgan N, Bayindir O, et al. Impact of renal function or folate status on altered plasma homocysteine levels in hypothyroidism. Endocrine Journal. 2006; 53(1): 119-124.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lindeman RD, Romero LJ, Schade DS, Wayne S, Baumgartner RN, Garry PJ.. Impact of subclinical hypothyroidism on serum total homocysteine concentrations, the prevalence of coronary heart disease (CHD), and CHD risk factors in the New Mexico Elder Health Survey. Thyroid. 2003; 13(6): 595-600.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Andrès E, Serraj K, Zhu J, Vermorken AJM. The pathophysiology of elevated vitamin B12 in clinical practice. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine. 2013; 106(6): 505-15.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Podzolkov VI, Dragomiretskaya NA, Dambaeva OT, Auvinen ST, Medvedev ID. Hypervitaminosis B12 - a new marker and predictor of prognostically unfavorable diseases. Therapeutic Archive. 2019; 91(8): 160-167.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rochat MC, Vollenweider P, Waeber G. Hypervitaminémie B12: implications cliniques et prise en charge [Therapeutic and clinical implications of elevated levels of vitamin B12]. Rev Med Suisse. 2012; 8(360): 2072-2074, 2076-2077.

[PubMed]

- Esnafoglu E, Ozturan DD. The relationship of severity of depression with homocysteine, folate, vitamin B12, and vitamin D levels in children and adolescents. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2020; 25(4): 249-255.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ebesunun MO, Eruvulobi HU, Olagunju T, Owoeye OA. Elevated plasma homocysteine in association with decreased vitamin B(12), folate, serotonin, lipids and lipoproteins in depressed patients. African Journal of Psychiatry. 2012; 15(1): 25-29.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]