Introduction

The COVID-19 virus originated in Wuhan and

has become a global pandemic. According to the

World Health Organization (WHO) update as

of the current research (8th March 2023), there

have been a total of 759,408,703 confirmed cases

of COVID-19 worldwide, with a death toll of

6,866,434. In Vietnam, there have been 11,526,966

confirmed cases of COVID-19, with 43,186 deaths [1]. This pandemic has not only caused

numerous economic, health, and social issues

but also significantly affected the mental health

of the population. Disease containment measures

such as social distancing have been implemented

to curb the spread of the virus, leading to various

socioeconomic problems such as unemployment,

income reduction, and isolation. These factors

contribute to increased stress [2-5]. Furthermore,

the fear and uncertainty surrounding the virus have also taken a toll on individuals’ mental well-

being, leading to heightened levels of anxiety and

depression. The long-term effects of the pandemic

on mental health are yet to be fully understood, but

it is clear that support and resources are crucial in

addressing these challenges. Studies on students

have shown that they have experienced increased

stress and dissatisfaction in their academic

performance since the outbreak of COVID-19 [6].

A longitudinal study conducted in Brazil found

that individuals in isolation due to COVID-19

experienced continuous stress over time [7]. These

findings highlight the importance of implementing

mental health interventions and support systems

to mitigate the negative impact of the pandemic

on individuals’ well-being. It is essential for

policymakers and healthcare providers to prioritize

mental health resources to address the ongoing

challenges faced by individuals during this time.

A population-based study in India also revealed

that 74% of participants reported experiencing

high levels of stress during the lockdown period

caused by the pandemic [8]. In Vietnam, several

reports have indicated that the disease has caused

stress in various population groups [9,10].

Therefore, the findings from this study can provide

valuable insights for policymakers and healthcare

professionals to develop targeted interventions

and support systems for those experiencing stress

related to the pandemic. By understanding the

extent of the problem, resources can be allocated

effectively to address mental health needs in

Vietnam during this challenging time.

Burnout is a syndrome consisting of emotional

exhaustion, depersonalization, and a diminished

sense of personal accomplishment [11]. It

is often experienced by individuals in high-

stress professions, such as healthcare workers

or first responders. Burnout can have serious

consequences on both the individual’s well-being

and their ability to perform effectively in their

job. Although work-related stress is considered

a primary cause, stress from other sources is

also recognized as a contributor to burnout [12].

Recently, the outbreak of COVID-19 has induced

high levels of stress across various aspects of

life. This has led to an increase in burnout among

individuals in various professions, as they struggle

to cope with the added pressures and uncertainties

brought on by the pandemic. It is important for

organizations to prioritize mental health support

and resources to help prevent and address burnout

in their employees during these challenging times.

Therefore, recent perspectives have focused on burnout with the origin attributed to the

COVID-19 pandemic [13,14]. Numerous studies

have also demonstrated that stress arising from

the COVID-19 pandemic is a significant factor

contributing to overall burnout in the population

[15,16]. It is crucial for organizations to implement

strategies such as flexible work arrangements,

mental health days, and employee assistance

programs to support their staff’s well-being. By

addressing burnout proactively, organizations

can help maintain a healthy and productive

workforce during these unprecedented times.

Moreover, Yıldırım and Solmaz emphasize the

urgency of understanding factors related to stress

and burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic

by understanding the central role of personality

strengths (e.g., resilience) as well as various other

factors to explain the relationship between stress

and burnout due to the coronavirus. Furthermore,

COVID-19 transmission misinformation influences the connection between COVID-19 stress and adult

life satisfaction. Individuals are more likely to access misinformation about Covid-19 transmission,

resulting in improved life satisfaction [16,17].

Theoretical approaches highlight the role of

coping mechanisms with stress, as it can lead

to various impacts on the mental health of

individuals. Research has shown that individuals

who utilize effective coping strategies are better

equipped to manage stress and maintain their

mental well-being. Understanding the different

coping mechanisms can help individuals develop

healthier ways of dealing with stressors in their

lives. According to Folkman, coping strategies

seem to depend on coping resources such as

psychological, mental, social, situational nature,

and, importantly, the individual’s ability to

control the situation [18]. Furthermore, many

studies suggest that coping strategies for stress

appear to be experiences distilled from previous

reactions and seem to become coping styles [19].

It is important for individuals to recognize their

own coping mechanisms and to cultivate positive

coping styles in order to effectively manage stress.

By understanding how coping strategies develop

and evolve, individuals can work towards building

resilience and maintaining their mental well-

being in the face of challenges. Therefore, coping

mechanisms may be somewhat independent of the

stressful situation. Coping styles are divided into

two types: positive coping and negative coping

[20]. Positive coping styles involve adaptive

strategies such as problem-solving, seeking social

support, and engaging in self-care activities.

On the other hand, negative coping styles may

include avoidance, denial, and substance abuse

as ways to deal with stress. In the context of

COVID-19, several studies indicate that positive

coping mechanisms, such as seeking social

support, problem-focused coping, and finding

meaning, are negatively correlated with burnout

and help overcome challenges better [21,22].

On the other hand, coping strategies that are

maladaptive to stress, such as avoidance, blaming,

and daydreaming, tend to be associated with an

increase in symptoms of depression, anxiety, and

burnout [22,23]. Therefore, we can assume that

coping styles may act as a moderating variable

in the relationship between stress and burnout

due to COVID-19. It is crucial for individuals to

recognize their coping styles and work towards

developing healthier mechanisms to navigate

through challenging situations effectively.

By addressing maladaptive coping strategies

and incorporating more positive approaches,

individuals can better manage stress and reduce

the risk of burnout during times of crisis like the

COVID-19 pandemic. This means that if positive

coping styles are applied, the impact of stress

on burnout will be low, and conversely, when

negative coping styles are used, the influence of

stress on burnout due to COVID-19 will increase.

Hypotheses

Hypothesis 1: Stress has a positive effect on

COVID-19-related burnout.

Hypothesis 2: Negative coping strategies play a

role in moderating the relationship between stress

and burnout related to COVID 19.

Hypothesis 3: Positive coping strategies play a

role in moderating the relationship between stress

and burnout related to COVID 19.

Materials and Methods

Participants

In this cross-sectional survey conducted during

the fourth wave of the COVID-19 pandemic

in Vietnam (June to September 2021), data

were collected through an online questionnaire

distributed to participants across various provinces.

The study garnered 3664 valid responses from

individual’s aged 18 to 75, comprising 17.6%

males and 82.4% females. Ethical considerations

were paramount, as all participants were explicitly

asked for voluntary and informed consent, and they retained the right to withdraw from the study

at any point without providing a reason. To ensure

participant confidentiality, their information was

strictly used for research purposes. Following their

participation, a token of appreciation was extended

to the respondents in the form of an E-book guide

designed to aid them in dealing with stress during

the ongoing pandemic. This comprehensive

approach aimed not only to capture a diverse and

representative sample but also to prioritize ethical

considerations, transparency, and participant wellbeing

throughout the survey process.

Measurement

Perceived stress related to COVID-19 was

measured using the Pandemic-Related Perceived

Stress Scale of COVID-19 [24]. This scale,

consisting of 10 items, assessed the stress levels

caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Items

included such statements as “I feel something

terrible related to the disease could happen at any

time,” “I am very anxious when things related to

the disease are beyond my control,” and “I can

cope with my difficulties even when infected.”

Participants provided feedback on a 5-point Likert

scale (0 corresponding to ‘never,’ 5 to ‘always’).

Positively framed items were reverse-coded for

score consistency. A higher total score on the

scale indicated higher stress levels. The study

demonstrated good reliability with a Cronbach’s

Alpha coefficient of 0.784.

A coping strategy checklist for stress was

developed based on a theoretical overview of

coping strategies, including 6 selected strategies

categorized as positive (seeking social support,

problem-focused, meaning-focused) and negative

(avoidance, blaming, wishful thinking). Results

were coded as 1 for not using and 2 for using each

coping strategy, and average scores for positive

and negative coping were calculated separately.

A lower score indicated a tendency not to use

coping strategies, while a higher score indicated a

tendency to use multiple coping strategies.

Burnout related to COVID-19 was measured

using the COVID-19 Burnout Scale [16]. This

scale, adapted from the Burnout Measure-Short

Version, comprised 10 items such as “I feel tired

when thinking about COVID-19,” “I feel bored/

downhearted when thinking about COVID-19,”

and “I feel helpless when thinking about

COVID-19” [25]. Participants provided feedback

on a 7-point Likert scale (1 corresponding to

‘never,’ 7 to ‘always’). A higher average score on the scale indicated higher COVID-19-related

burnout. The study demonstrated excellent

reliability with a Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of

0.94.

Analysis

The software SPSS version 22.0 was used to

process the data in this study. Firstly, we conducted

descriptive statistics analysis on the demographic

characteristics of the participants in the research. To

examine the moderating role of coping strategies

in the relationship between stress and burnout

related to COVID-19, we initially explored the

correlation between the study variables. According

to Baron and Kenny, the conditions for a variable

to act as a moderating variable are (1) this

variable should have no relationship between the

independent and dependent variables, and (2) the

product of the independent variable and the tested

moderating variable should impact the dependent

variable [26]. However, the current approach

only requires the satisfaction of condition 2 for a

variable to be considered a moderating variable,

and both methods are widely accepted. Therefore,

we used the three-step hierarchical regression

model to test. In Model 1, the independent

variable is COVID-19-related stress, and the

dependent variable is COVID-19-related burnout.

In Model 2, we examined the moderating role of

negative coping strategies with stress. In Model

3, we examined the moderating role of positive

coping strategies with stress. However, in Models

2 and 3, since there is a product term between

stress related to COVID-19 and coping strategies,

multicollinearity issues may arise. Following the

recommendation of McClelland et al., to avoid

this issue when analyzing moderation models,

we applied the centering method (center mean)

to the independent variables in the model before

conducting the regression analysis [2].

Ethical statement

The study was approved by the Ethical Council of

Vietnam Psychological Association.

Results

Table 1 shows some demographic characteristics

of the 3664 study participants. The data indicates

that 17.6% of the participants are male, and

82.4% are female. Regarding age, the number

of participants aged 18-25 is 1528 (41.70%), 26-

35 is 868 (23.69%), 36-45 is 855 (23.34%), 46-

55 is 370 (10.10%), 56-65 is 37 (1.01%), and 65 and above is 6 (0.16%). In terms of educational

attainment, the number of participants with

primary education is 43 (1.20%), lower secondary

education is 114 (3.10%), upper secondary

education is 198 (5.40%), vocational training is

366 (10.00%), college and university education is

2589 (70.70%), and postgraduate education is 354

(9.70%). Regarding marital status, the number of

single participants is 1662 (45.40%), married is

1890 (51.60%), divorced/separated is 96 (2.60%),

and widowed is 16 (0.40%). As for income, the

number of participants with comfortable spending

is 58 (1.60%), relatively comfortable spending

is 276 (7.50%), normal living expenses is 2204

(60.20%), slightly insufficient spending compared

to normal living is 881 (24.00%), and insufficient

spending for minimum living is 245 (6.70%) (Table 1).

Table 1. Some characteristics of the research participants

| Characteristics |

Classification |

Number |

Proportion |

| Gender |

Nam |

644 |

17.6 |

| Nu |

3020 |

82.4 |

| Age |

18-25 |

1528 |

41.7 |

| 26-35 |

868 |

23.69 |

| 36-45 |

855 |

23.34 |

| 46-55 |

370 |

10.1 |

| 56-65 |

37 |

1.01 |

| 66-75 |

6 |

0.16 |

| Education |

Primary education |

43 |

1.2 |

| Middle school |

114 |

3.1 |

| High school |

198 |

5.4 |

| Intermediate level |

366 |

10 |

| Colleges and universities |

2589 |

70.7 |

| Post universities |

354 |

9.7 |

| Marital status |

Single |

1662 |

45.4 |

| Married |

1890 |

51.6 |

| Divorce/Separation |

96 |

2.6 |

| Widow |

16 |

0.4 |

| Income |

Spend freely according to your needs |

58 |

1.6 |

| Spending at a relatively decent level of life security |

276 |

7.5 |

| Spending at a level that ensures a normal life |

2204 |

60.2 |

| Spending is a little short of normal living standards |

881 |

24 |

| Not enough to spend on the minimum standard of living |

245 |

6.7 |

| Total |

3664 |

100 |

Note: N=3664. |

Table 2 presents descriptive and correlation

statistics between stress, coping, and burnout

related to COVID-19. The data shows that the

stress and burnout related to COVID-19 have

a statistically significant correlation (r=0.40,

p<0.001). The relationship between stress and

positive coping strategies with stress related to

COVID-19 is not statistically significant (r=0.03,

p>0.05). Negative coping is positively correlated

with stress and burnout (r=0.19, p<0.001 and

r=0.31, p<0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and correlations between research variables

| Variables |

Mean |

Std. Deviation |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| Stress |

19.64 |

5.6 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Burnout |

2.4 |

1.1 |

0.41* |

- |

- |

- |

| Negative coping |

1.33 |

0.31 |

0.19* |

0.31* |

- |

- |

| Positive coping |

1.65 |

0.29 |

0.03 |

0.03 |

0.19* |

- |

Note: N=3664; *Correlation is statistically significant at 0.01. |

Table 3 illustrates various models designed to

examine the moderating role of coping strategies in

the relationship between stress and burnout related

to the COVID-19 pandemic. The data in Model 1

indicates that stress has a statistically significant

positive impact on COVID-19-related burnout

(beta=0.41, t=26.79, p=0.000, VIF=1.00), and this

model explains 16.4% of the variance in fatigue.

In Model 2, stress continues to positively impact

burnout (beta=0.37, t=24.49, p=0.000, VIF=1.06).

Negative coping strategies also have a statistically

significant positive effect on burnout (beta=0.24,

t=15.94, p=0.000, VIF=1.04). The interaction

effect between stress and negative coping on

burnout is positive and statistically significant

(beta=0.06, t=4.07, p=0.000, VIF=1.02) (Table 3)

Table 3. Examining the moderating role of coping strategies

| Model |

Variable |

Beta |

t |

Sig. |

VIF |

|

| 1 |

(Constant) |

- |

144.55 |

0 |

- |

ΔR²=0.164* |

| Stress |

0.41 |

26.79 |

0 |

1 |

| 2 |

(Constant) |

- |

146.07 |

0 |

- |

ΔR²=0.060* R²=0.223* |

| Stress |

0.37 |

24.49 |

0 |

1.06 |

| Negative coping |

0.24 |

15.94 |

0 |

1.04 |

| Negative coping x Stress |

0.06 |

4.07 |

0 |

1.02 |

| 3 |

(Constant) |

|

146.31 |

0 |

|

ΔR²=0.003** R²=0.226* |

| Stress |

0.37 |

24.38 |

0 |

1.06 |

| Negative coping |

0.24 |

16.01 |

0 |

1.08 |

| Negative coping x Stress |

0.06 |

4.24 |

0 |

1.03 |

| Positive coping |

-0.03 |

-2.13 |

0.033 |

1.04 |

| Positive coping x Stress |

-0.04 |

-2.87 |

0.004 |

1.02 |

| Note: N=3664; Dependent variable=burnout; *Statistically significant at 0.001;**Statistically significant at 0.01. |

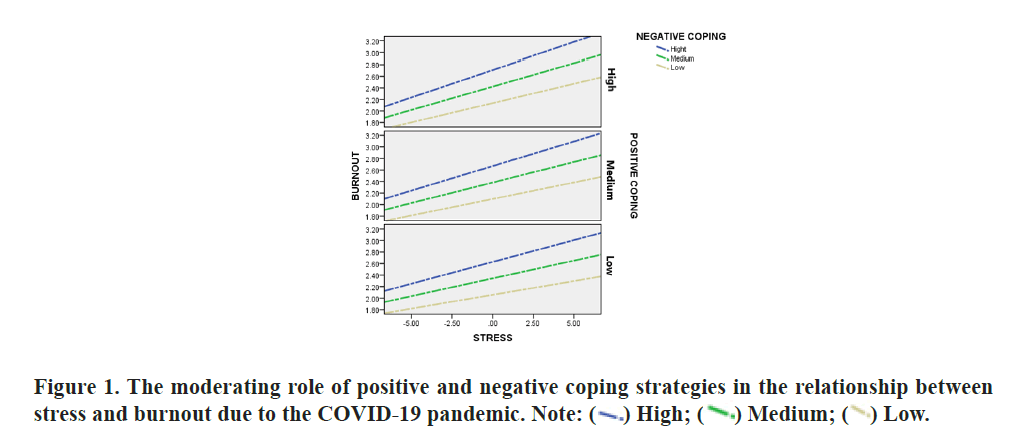

Therefore, negative coping is identified as a

significant moderating variable in the relationship

between stress and COVID-19-related fatigue.

In Model 3, stress continues to have a positive

impact on burnout (beta=0.37, t=24.38, p=0.000,

VIF=1.06), and negative coping still plays a

moderating role in this relationship (beta=0.06,

t=4.24, p=0.000, VIF=1.03). Additionally, the influence of the interaction between positive

coping and stress on COVID-19-related burnout

is negative and statistically significant (beta=-

0.04, t=-2.87, p=0.004, VIF=1.02). Therefore, it can be concluded that positive coping strategies

also moderate the relationship between stress and

COVID-19-related burnout as shown in Figure 1.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on the burnout of the overall population. Numerous studies have also indicated that stress can increase the risk of pandemic-related burnout [16]. Many researchers have sought to explore the mechanisms and factors influencing this relationship. Factors such as resilience, social support, and a sense of belonging have been identified as crucial elements [27,28]. However, the moderating role of coping strategies in stress has been less explored. Therefore, this study aims to examine the moderating role of positive and negative coping strategies in the relationship between stress and pandemic-related exhaustion.

Firstly, our research data revealed that stress positively influences pandemic-related exhaustion. This confirms the accuracy of hypothesis 1, suggesting that individuals experiencing more stress due to COVID-19 are more likely to experience burnout. This finding highlights the importance of addressing stress management in interventions aimed at reducing pandemic-related exhaustion. Future studies could explore specific coping mechanisms that may mitigate the impact of stress on burnout during times of crisis. This result aligns with previous studies examining this relationship in various groups, including healthcare professionals and community samples [15,16]. Understanding the role of stress in burnout during a crisis like COVID-19 can inform targeted interventions to support individuals in managing their well-being. By identifying effective coping strategies, researchers and practitioners can better equip individuals to navigate high-stress situations and prevent burnout.

Another significant finding of this study is that the relationship between stress and pandemicrelated burnout is moderated by positive coping strategies. The observed coefficient is positive, indicating that individuals who tend to use more positive coping mechanisms will increase the impact of stress factors on pandemic-related burnout. These findings suggest that interventions aimed at promoting positive coping strategies could potentially help mitigate the negative effects of stress on burnout during a pandemic. It is important for individuals to be aware of their coping mechanisms and work towards incorporating more positive strategies into their daily routines. Conversely, individuals using fewer negative coping strategies may mitigate the impact of this relationship. This result supports hypothesis 2 and is consistent with prior research suggesting that maladaptive coping strategies against stress are often associated with increased burnout [22,23]. Overall, understanding the relationship between coping strategies and burnout can provide valuable insights for individuals seeking to improve their mental health and well-being. By identifying and implementing effective coping mechanisms, individuals may be better equipped to navigate challenging situations and prevent burnout from occurring. Additionally, hypothesis 3 is confirmed as the data shows that positive coping strategies also play a moderating role in this relationship. However, unlike negative coping strategies, we observed a negative moderation coefficient. This implies that individuals who frequently use positive coping mechanisms may reduce the impact of stress on burnout. This result is consistent with previous research indicating that adaptive positive coping strategies can lower the risk of exhaustion and improve problemsolving abilities [21,22]. The findings suggest that promoting positive coping strategies can be an effective way to prevent burnout and enhance overall well-being in individuals facing high levels of stress. Future research could further explore the specific types of positive coping mechanisms that are most beneficial in mitigating burnout. Therefore, focusing on positive coping strategies may help alleviate the impact of stress on pandemic-related burnout. Interventions aimed at enhancing positive coping skills could be implemented in various settings to support individuals in managing stress effectively. By incorporating these strategies into daily routines, individuals may experience improved mental health outcomes and a greater sense of resilience in the face of adversity.

Another notable result is that while positive coping strategies seem to operate independently of stress, they can still participate in regulating the relationship between stress and burnout. This suggests that individuals who utilize positive coping strategies may be better equipped to manage the effects of stress and prevent burnout. By actively engaging in healthy coping mechanisms, individuals may be able to buffer the negative impact of stress on their well-being. In contrast, negative coping strategies show a positive correlation with stress. This seemingly contradictory result is explained by Folkman, who suggests that coping strategies depend on individual assessments of situations, resources, abilities, and habits [14]. Individuals who tend to use avoidance or maladaptive coping mechanisms may find themselves more susceptible to burnout due to the compounding effects of stress. Therefore, it is crucial for individuals to develop self-awareness and cultivate positive coping strategies in order to effectively manage stress and prevent burnout in the long term. Therefore, if an individual evaluates a situation positively, it may lead to negative emotions and subsequently to maladaptive coping strategies like avoidance and escape [29]. This is likely associated with negative outcomes, including burnout [22]. In contrast, according to Stress Appraisal Theory, stress allows individuals to expand their knowledge and experience while developing additional skills to face future challenges or stressors [30]. However, only positive coping mechanisms in response to new situations can have such an impact. Therefore, individuals may have specific coping styles and skills influenced by their previous experiences and learning [19]. In essence, the way individuals cope with stress can greatly impact their overall wellbeing and resilience. It is crucial for individuals to develop healthy coping mechanisms in order to effectively navigate through challenging situations and prevent burnout. Together with the other findings, these results provide a basis for constructing effective positive coping strategies and minimizing negative coping behaviors to avoid negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, these findings may serve as a foundation for implementing educational methods and experiences to foster positive coping styles in individuals facing life stressors. By focusing on promoting positive coping strategies, individuals can better manage stress and maintain their mental health during difficult times. Educators and mental health professionals can use these findings to tailor interventions that support individuals in developing effective coping mechanisms for longterm well-being.

The implications derived from this study carry significant ramifications for interventions and strategies to address the profound impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on burnout and overall wellbeing. Primarily, there is a pressing need for targeted stress management interventions that recognize and address the unique stressors associated with the pandemic. By tailoring support mechanisms to specific challenges, interventions can better equip individuals to navigate these stressors and prevent burnout. Moreover, the study emphasizes the pivotal role of coping strategies in shaping the stress-burnout relationship. Positive coping mechanisms, identified as problem-solving and adaptive strategies, should be actively promoted through educational programs and integrated into daily routines. Simultaneously, interventions should discourage maladaptive coping strategies to avoid exacerbating the negative effects of stress. The findings underscore the importance of individual awareness and self-reflection regarding coping styles, enabling individuals to make informed choices in managing stress. Encouraging the integration of positive coping strategies into daily routines emerges as a practical approach to fostering resilience and maintaining mental health. Educational institutions and workplaces can utilize these insights to tailor programs that specifically address the development of effective coping mechanisms, ensuring a holistic approach to well-being. Policymakers are urged to consider the implications when crafting public health strategies, emphasizing investments in mental health resources, the integration of stress management programs, and policies that champion positive coping strategies. Ultimately, the study provides a comprehensive framework for constructing effective coping strategies and minimizing negative behaviors, offering a roadmap to mitigate the adverse effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and enhance long-term individual well-being.

This study, while offering valuable insights, is subject to several limitations that warrant consideration. The cross-sectional design employed hinders the establishment of causal relationships, preventing definitive conclusions about the temporal sequence of stress, coping strategies, and burnout. A longitudinal approach would better capture the dynamic nature of these variables over time. The reliance on selfreported data introduces the possibility of common method bias and social desirability bias, potentially influencing the accuracy of reported stress levels, coping mechanisms, and burnout experiences. Future research should incorporate diverse methodological approaches to enhance the validity of the findings. Additionally, the study’s generalizability is constrained by the potential sample bias, as participants may not fully represent the broader population. To address this, researchers should strive to include more diverse and representative samples in future studies. The study’s exclusive focus on the COVID-19 pandemic, while contextually relevant, may limit the generalizability of findings to other stressinducing scenarios. Exploring the transferability of these insights across various contexts will contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of stress-coping dynamics. Despite these limitations, this study provides a foundational understanding of the interplay between stress, coping strategies, and burnout during the pandemic. Acknowledging and addressing these limitations in future research endeavors will contribute to refining our understanding of individual responses to stress and inform more effective interventions in diverse settings.

Conclusion

This study adds to the literature on pandemicrelated

burnout by examining its predictors. Stress

can be a motivation and a hinderance to one’s

mental health and daily functioning, and this

study leans more towards the negative impacts

of stress, as it can contribute to exhaustion. Our

findings found that stress had a direct relationship

with pandemic-related exhaustion. More

importantly, this relationship was moderated

by coping style. Positive coping strategies help

reduce the impacts of stress on burnout; while

negative coping strategies were not only related

to stress but also enhanced the impacts of stress

on burnout. This study therefore highlighted the

role of both stress and coping mechanisms in

predicting burnout. This study showed that to

prevent burnout, in particular pandemic-related

burnout, it is important to educate the public about

stress management and positive coping. If left

unaddressed, stress can increase burnout, as well

as promoting negative coping mechanisms, which

in return further increases burnout. Therefore,

public health programs can educate people about

the impacts of stress and stress management

strategies, especially positive coping strategies

like seeking social support, reframing problems

in positive meaning and directly dealing with the

problems.

References

- WHO. WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) dashboard. 2023.

- McClelland GH, Irwin JR, Disatnik D, Sivan L. Multicollinearity is a red herring in the search for moderator variables: A guide to interpreting moderated multiple regression models and a critique of Iacobucci, Schneider, Popovich, and Bakamitsos (2016). Behav Res Methods. 2017;49:394-402.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pancani L, Marinucci M, Aureli N, Riva P. Forced social isolation and mental health: A study on 1,006 Italians under COVID-19 lockdown. Front Psychol. 2021;12:663799.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tran BX, Nguyen HT, Le HT, Latkin CA, Pham HQ, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on economic well-being and quality of life of the Vietnamese during the national social distancing. Front Psychol. 2020;11:565153.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Upadyaya K, Toyama H, Salmela-Aro K. School principal’s stress profiles during COVID-19, demands, and resources. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021;12:731929.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ihm L, Zhang H, van Vijfeijken A, Waugh MG. Impacts of the Covid‐19 pandemic on the health of university students. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2021;36(3):618-627.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Blacutt M, Filgueiras A, Stults-Kolehmainen M. Changes in stress, depression, and anxiety symptoms in a Brazilian sample during quarantine across the early phases of the COVID-19 Crisis. Psychol Rep. 2023:00332941231152393.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pal K, Danda S. Stress, anxiety triggers and mental health care needs among general public under lockdown during COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study in India. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2023;21(1):321-332.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Luong TN. Status of mental health of medical staff at Hanoi Obstetric Hospital and related factors. Vietnam Medical Journal. 2022;519(2).

- Thai TT, Le PT, Huynh QH, Pham PT, Bui HT. Perceived stress and coping strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic among public health and preventive medicine students in Vietnam. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2021;14:795-804.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach burnout inventory. Scarecrow Education. 1997.

[Google Scholar]

- Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52(1):397-422.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Ye B, Chen X, Zhang Y, Yang Q. Psychological flexibility and COVID-19 burnout in Chinese college students: A moderated mediation model. J Contextual Behav Sci. 2022;24:126-133.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yıldırım M, Cicek İ, Sanlı ME. Coronavirus stress and COVID-19 burnout among healthcare staffs: The mediating role of optimism and social connectedness. Curr Psychol. 2021;40(11):5763-1571.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Moroń M, Yildirim M, Jach Ł, Nowakowska J, Atlas K. Exhausted due to the pandemic: Validation of Coronavirus Stress Measure and COVID-19 Burnout Scale in a Polish sample. Curr Psychol. 2021:1-10.

[Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yıldırım M, Solmaz F. COVID-19 burnout, COVID-19 stress and resilience: Initial psychometric properties of COVID-19 Burnout Scale. Death Stud. 2022;46(3):524-532.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nguyen PT, Van Huynh S, Nguyen NN, Le TB, Le PC, et al. The relationship between transmission misinformation, COVID-19 stress and satisfaction with life among adults. Front Psychol. 2023;13:1003629.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Folkman, S. Stress: Appraisal and Coping. Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine. 2013: pp. 1913-1915.

- Villada C, Hidalgo V, Almela M, Salvador A. Individual differences in the psychobiological response to psychosocial stress (Trier Social Stress Test): The relevance of trait anxiety and coping styles. Stress Health. 2016;32(2):90-99.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Folkman S, Moskowitz JT. Positive affect and the other side of coping. Am Psychol. 2000;55(6):647-654.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- AlJhani S, AlHarbi H, AlJameli S, Hameed L, AlAql K, et al. Burnout and coping among healthcare providers working in Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 pandemic. MECP. 2021;28(1):29.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Lou NM, Montreuil T, Feldman LS, Fried GM, Lavoie-Tremblay M, et al. Nurses' and physicians' distress, burnout, and coping strategies during COVID-19: Stress and impact on perceived performance and intentions to quit. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2022;42(1):e44-e52.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mong M, Noguchi K. Emergency room physicians’ levels of anxiety, depression, burnout, and coping methods during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Loss Trauma. 2022;27(3):212-228.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Campo-Arias A, Pedrozo-Cortes MJ, Pedrozo-Pupo JC. Pandemic-Related Perceived Stress Scale of COVID-19: An exploration of online psychometric performance. Rev Colomb Psiquiatr (Engl Ed). 2020;49(4):229-230.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Malach-Pines A. The burnout measure, short version. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2005;12(1):78-88.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173-1182.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu Y, Zou L, Yan S, Zhang P, Zhang J, et al. Burnout and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms among medical staff two years after the COVID-19 pandemic in Wuhan, China: Social support and resilience as mediators. J Affect Disord. 2023;321:126-133.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Veronese G, Mahamid FA, Bdier D. Subjective well-being, sense of coherence, and posttraumatic growth mediate the association between COVID-19 stress, trauma, and burnout among Palestinian health-care providers. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2022;92(3):291-301.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lazarus RS. Emotion and adaptation. Oxford University Press. 1991.

[Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer publishing company. 1984.

[Google Scholar]

Citation: Stress in relationship with burnout due to COVID-19: the moderating role of coping strategies ASEAN Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 25 (3) March, 2024; 1-10.

) High; (

) High; ( ) Medium; (

) Medium; ( ) Low

) Low