Introduction

South Suicide is a serious public health concern

worldwide, ranking as the fourth leading cause

of death among 15-29 year old and the third

among girls 15-19 years old [1]. WHO reported

that there would be an estimated 804,000 suicide

deaths worldwide in 2021. The World Health

Organization defined suicidal behavior as a

range of behaviors that include thinking about

suicide or ideation, planning for suicide,

attempting suicide, and suicide itself. Suicidal

behavior can be considered to consist of ideation, attempt, and suicide. Suicide is the act of

deliberately killing oneself [2]. In the

Philippines, around 3.2 deaths relating to suicide

were recorded per 10,000 inhabitants in 2011 [3].

The Philippine Statistical Authority (PSA)

recorded 3,529 death cases due to intentional

self-harm in 2020. Usually, those who commit

suicide tend to be older, male, use more lethal

methods, and die on the first attempt [4].

Moreover, official suicide rates are lower in the

Philippines as compared with many other

countries. Very likely that suicide cases were

underreported due to cultural differences such as religious beliefs, stigma to the families, and lack

of understanding on suicide.

The Philippines today according to the United

Nations Population Fund has the largest

generation of young people in our history. Thirty

(30) million young people between ages of 10 to

24 account for 28 percent of Philippine

population and about 19.8 million are adolescent.

Said organization clearly emphasized that

developing policies and investments for the

future of these young people could lead the

Philippines to reap the benefits of a demographic

dividend-the economic growth potential that can

result from shifts in a population’s age structure,

mainly when the share of the working-age

population is larger than the non-working-age

share of the population or the dependent

population. Yet, these young people are also

facing different challenges and even lifethreatening

risks such as suicidal behaviour. The

study conducted by Refaniel, et al. through data

review for suicide deaths between 1974 and 2005

obtained from Philippines Health Statistics

reported that suicide rates were highest in 15-24

year-old in females and surprising suicide rates

were increasing every year. Further, the

identified most commonly used method for

suicide was hanging, shooting, and

organophosphate ingestion [5].

Suicide has a devastating and long-lasting impact

on families, friends, and communities; however,

suicide has no known definite cause [6]. There is

no single factor that would explain why the

individuals take their own life or why they hurt

themselves. Suicidal behavior is a complex

phenomenon influenced by several interacting

factors such as personal, social, psychological,

cultural, biological, and environmental [2].

Previous studies have reported several risk

factors associated with suicidal behavior among

young people. Psychological risk factors related

to suicidal behavior were depressive moods,

substance use, and history of severe

psychopathology [7-12]. Moreover, with regards

to personal, social, and environmental factors,

suicide behavior was found to be associated with

unemployment, low educational attainment, not

studying, and low achievement family problems, bullying victimization, no or few friends, food

insecurity, female sex, LGBTQ+ gender

orientation, sleep problems, and obesity [13-16].

Existing literature showed suicidal behavior was

negatively associated with religious affiliation;

social support, parent-family connectedness, and

positive affect [11,17-21]. However, very little

research has focused on protective factors

because most studies highlighted the negative or

the risk factors [22-24].

This study aimed to investigate the prevalence of

suicidal behavior among college students in a

state university in Pampanga and examined the

risk and protective factors most associated with

suicidal behavior. This current study is essential

to provide a picture of the size of the problem

and facilitate better-informed decisions, and

formulate potential etiologies and preventive

actions in the state university [5,25,26].

Materials and Methods

Research design

A cross-sectional survey was utilized to

determine the prevalence of suicidal behaviors

and examined the association of risk and

protective factors among college students in state

university in Pampanga.

Study population and sample

Pampanga is located on the northwest of Manila.

It has an estimate of 2.5 M population and the

age group with the highest population in this

province is 15 to 19 years old. The survey was

conducted on college students in a state

university in Pampanga during the academic year

of 2021-2022. A minimum of 385 college

students is required to achieve a 95% level of

confidence, precision of 5% given an estimated

prevalence of suicidal behaviors of 50%. All

colleges were included in the sample range using

a cluster sampling. A total of 443 students were

voluntarily participated in the study.

Data collection procedure

An online survey was created using Jotform

(https://www.jotform.com). Information about the study was placed at the beginning of the

survey and was followed with an online

informed consent form. Only participants who

voluntarily agree to participate in the study were

included in the survey. The online survey

included questions on demographic

characteristics of the participants such as age,

gender, year level, academic status, and the

seven (7) self-report standardized questionnaires.

The online survey’s duration was approximately

20-25 minutes. The link to the study was

distributed through the student leader per class.

The link remained active for one month during

the month of June 2022. The study complied

with the ethical guidelines of the state university.

Instruments

Suicidal behaviour: The Suicide Behaviors

Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R) developed

Osman et al. was used to assess the suicidal

behaviors of the participants. The scale consists

of 4-itmes, each item tapping a different

dimension of suicidality such as suicide ideation,

plan, and attempt. SBQ-R is a useful measure of

suicidal behavior based on empirical studies.

Symptoms of depression: Patient Health

Questionnaire (PHQ-9) is a nine-item scale

assessing the presence of depressive symptoms

over the past two weeks.

Childhood trauma history: The Adverse

Childhood Experiences (ACEs) Questionnaire is

a 10-item measure used to measure childhood

trauma. The questionnaire assesses 10 types of

childhood trauma measured in the ACE Study.

Personal: Physical abuse, verbal abuse, sexual

abuse, physical neglect, and emotional neglect.

This scale has good internal validity (Cronbach’s

Alpha=0.854) and predictive validity (R2=0.12,

p0.001 of the SHI total score). The items are

rated on a 4-point Likert scale, except for seven

items. Higher scores indicate greater exposure to

childhood maltreatment.

Gender identity: Gender identity was

determined by single question, “What is your

current gender identity?”

Family and social connectedness: The

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social

Support is a 12-item measure of perceived

adequacy of social support from three sources:

Family, friends, and significant other; using a 5-

point Likert scale (0=strongly disagree,

5=strongly agree). MSPSS has been widely used

in both clinical and non-clinical samples and

easily administered using a five-point Likert-type

scale. The internal consistency of the scale was

good, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.91 with

students.

Positive affect: The Positive and Negative

Affect Scale (PNAS) is one of the most widely

used scales to measure mood or emotion. This

brief scale is comprised of 20 items, with 10

items measuring positive affect (e.g., excited,

inspired) and 10 items measuring negative affect

(e.g., upset, afraid).

Spirituality: The Spiritual Well Being Scale

(SWBS) is a 20 item scale that measures an

individual's well-being and overall life

satisfaction on two dimensions: (1) religious

well-being, and (2) existential well-being. Items

related to religious well-being contain the word

"God" and measure the degree to which one

perceives and reports the well-being of his or her

spiritual life in relation to God. Items related to

existential well-being contain general statements

that ask about life direction and satisfaction and

measure the degree to which one perceives and

reports how well he or she is adjusted to self,

community, and surroundings.

Data analysis

The data were analysed using the Statistical

Package for Social Science (SPSS v.26, IBM

Corp, 2019). Frequency and percentage were

used to describe the characteristics of the

respondents. Multiple logistic regressions were

performed to assess how well the risk and

protective factors predict or explain the college

students’ suicidal behavior. It also allows to test

models to predict categorical outcomes withs

two or more categories (non-suicide, suicide

ideation, plan, and attempt). And the predictor

variables can be either categorical (gender, with

history and no history of adverse childhood experience) or continuous (depressive symptoms,

support from significant others, support from

family, support from friends, positive affect,

negative affect, spiritual well-being, and age).

Results

Table 1 shows the study’s descriptive results. A

total of 443 college students voluntarily

participated in the study. Majority of the

participants were female (65%) and third year

college students (41.5%).

| Variables |

Non-suicidal (n=233) |

Suicide Risk Ideation (n=108) |

Suicide Plan (n=62) |

Suicide Attempt (n=40) |

| Gender |

Male |

91 (39.1%) |

22 (20.4%) |

14 (22.6%) |

11 (27.5%) |

| Female |

135 (57.9%) |

82 (75%) |

44 (71%) |

27 (67.5%) |

| LGBTQ+ |

7 (3%) |

4 (3.7%) |

4 (6.5%) |

2 (5%) |

| Year Level |

First |

36 (15.5%) |

30 (27.8%) |

10 (16.1%) |

10 (25%) |

| Second |

15 (11.6%) |

15 (13.9%) |

12 (19.4%) |

8 (20%) |

| Third |

101 (43.3%) |

42 (38.9%) |

25 (40.3%) |

16 (40%) |

| Fourth |

68 (29.2%) |

21 (19.4%) |

15 (24.2%) |

6 (15%) |

| Fifth |

1 (0.4%) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Table 1: Demographic profile of the participants.

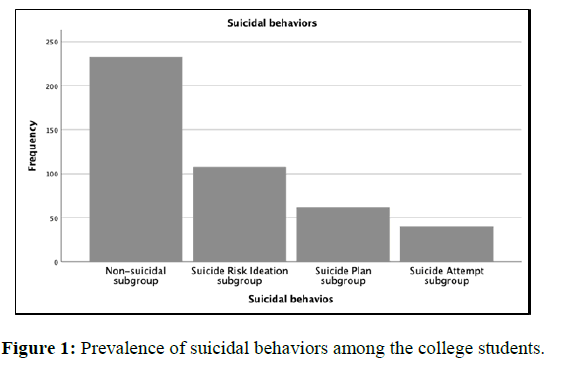

According to Figure 1, most of the participants

do not engage in suicidal behavior, 52.60% 28.5)

of the participants reported suicidal ideation and

14% (95%, CI 11.07, 17.54) indicated they had

suicidal plans (Figure 1). Moreover, 9% (95%,

CI 6.7, 12.06) of the college students confessed

that they would attempt to commit suicide.

Majority of these students who reported with

suicidal behaviors were female and third year

college students. Multinomial Regression

Analysis was performed to assess the impact of a

number of protective and risk factors on the

likelihood that respondents would report that

they had any suicidal behavior. Preliminary

analyses were conducted to ensure no violation

of the assumptions of normality, linearity,

multicollinearity and homoscedasticity. The

model contained ten independent variables

(depressive symptoms, adverse childhood

experience, support from significant others,

support from family, support from friends,

positive affect, negative affect, spiritual wellbeing,

age, and gender). The whole model

containing all predictors was statistically

significant, x2 (33, N=443) = 279.115, p<0.001,

indicating that the model could distinguish

between respondents who have suicidal behaviors and those who are not suicidal. The

model explained 46.8% (Cox and Snell R

square) and 51.8% (Nagelkerke R square) of the

variance in types of suicidal behaviors

committed by college students.

As shown in Table 2, only four independent

variables made a unique statistically significant

contribution to the model (depressive symptoms,

adverse childhood, support from family, spiritual

well-being). The strongest predictor of not

committing suicide was having family support,

recording an odds ratio of 2.55. The results

indicated that respondents who had good social

support from their families were over 2.55 times

more likely to prevent themselves from

attempting to commit suicide. The odds ratio of

1.040 for spiritual well-being is also shown in

the table, indicating that students with good

spiritual well-being would likely not attempt

suicide. On the contrary, the odds ratio of .83 for

depressive symptoms and the odds ratio of .42

for adverse childhood experiences were less than

1, indicating that for every one-point increase in

the scores of symptoms of depression and adverse childhood experiences were .83 and .42

times more likely to have a suicide attempt.

| Reference: Suicide attempt |

Non-suicidal OR (Std. Err) |

Suicide risk ideation OR (Std. Err) |

Suicide plan OR (Std. Err) |

| Depressive symptoms |

0.83 (0.0)*** |

0.91 (0.05) |

0.96 (0.05) |

| Adverse childhood experiences |

0.42 (0.17)*** |

0.79 (0.13) |

0.93 (0.14) |

| Support from significant other |

0.70 (0.23) |

0.75 (0.21) |

0.80 (0.22) |

| Support from family |

2.55 (0.29)*** |

1.84 (0.26)* |

0.88 (0.27) |

| Support from friends |

0.93 (0.27) |

0.90 (0.24) |

0.70 (0.25) |

| Positive affect |

1.04 (0.04) |

1.02 (0.03) |

0.95 (0.04) |

| Negative affect |

0.95 (0.04) |

1.00 (0.04) |

0.91 (0.04) |

| Spiritual well-being |

1.04 (0.02)* |

1.02 (0.02) |

0.98 (0.02) |

| Age |

1.37 (0.17) |

1.22 (0.16) |

0.87 (1.28) |

| Male |

0.93 (1.10) |

0.751 (1.04) |

0.07 (1.03) |

| Female |

2.03 (1.05) |

2.31 (0.97) |

0.20 (0.95) |

| LGBTQ+ |

-- |

-- |

-- |

| Note: P-value. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 |

Table 2: Demographic profiles, protective and risk factors as predicting factors of suicidal behaviors with suicidal attempt as reference group

Further, the results show an odds ratio of 1.84 for

social support from the family, indicating that

those students who received support from the

family will be more likely to have suicide risk

ideation than a suicide attempt. Times more

likely to have a suicide attempt.

Discussion

College students in Pampanga were investigated

for suicidal behavior such as suicide ideation and

attempts and for the risk and protective factors

most commonly associated with these behaviors.

There were 443 college students who

volunteered to participate in the study, most of

whom were female and in their third year.

Approximately 24% of participants reported

suicidal ideation and 14% reported suicide plans.

9% of them had attempted suicide. An analysis

of the model revealed statistically significant

contributions from four independent variables.

Family support was found to be a strong protective factor against suicide attempts. In

addition, spiritual well-being prevents suicide

attempts. Depression and adverse childhood

experiences, however, were both found to be risk

factors for suicide attempts among college

students. Age and gender preferences were not

found associated with suicidal behaviors.

In a recent meta-analysis by the prevalence in

suicidal intention was 9.7% to 58.3% and in

suicide attempts was 0.7% to 14.7% among

university students. Suprisingly, suicidal ideation

was relatively stable before and during the

pandemic, as a previous study reported that the

national rate of Sta. Maria and her colleagues in

2015 accounted for 24% of Filipino college

student before the pandemic, and as shown in

this study. However, suicidal attempts in the

present study was relatively higher than with the

National Survey of Philippine Youth in 2021,

amid the COVID-19 pandemic, it was reported

that 7.5% young people have attempted ending

their life [27]. In the midst of the pandemic,

prolonged stay at home, attendance of online

classes and difficulty obtaining mental health

services may increase the suicidal attempts

among college students. Thus, a careful

consideration of this should be given by

universities when planning for future disasters

that might allow students to seek assistance.

Moreover, family support may play important

role in preventing suicide attempts and ideation,

which led to a very high likelihood of not

committing suicide. Individuals who perceived

that their families supported and provided care to

them during the pandemic were less likely to

contemplate or attempt suicide. As previously

shown in the literature, parental care was

considered as protective factor for suicide among

adolescents and young adults [28,29]. In fact,

family problems including parental separation

and conflict among the members can contribute

to suicidal behavior in young people [30].

Research shows that college students are better

able to cope in times of crisis if their families are

providing them with appropriate assistance,

especially if they remain at home for a longer

period of time. However, young adults may fear

being discriminated against and rejected by their families if they reveal their suicidal intentions

and intentions. While the decision to attempt

suicide is highly personal, receiving care from

their family is important to them, since they are

aware of the consequences of their actions.

In addition to the aforementioned family support

associated with suicidal behaviors as protective

factor, spiritual well-being has found as another

significant protective factor against suicidal

behavior. Students who have a subjective sense

of spiritual satisfaction have a lower risk of

suicidal behavior. Research conducted by

Ibrahim et al., has found that spiritual wellbeing

negatively correlated with suicidal ideation [31].

In alignment with this study, a meta-analysis

revealed that a spiritual activity was negatively

associated with suicide behaviors [32].

University students may benefit from spiritual

wellbeing in managing negative emotions during

difficult times [33]. There are many aspects of

spirituality, including belief in a higher power,

transcendence, prayer, hope, unity with nature,

and connection to others. During the pandemic,

Walsh suggests that transcendent values may

provide meaning, purpose, harmony, and

connection for individuals to cope with loss [34].

Particularly, existential spirituality appears to be

the aspect of spirituality most strongly associated

with suicidality [35].

Furthermore, in terms of risk factors, suicide

attempts were significantly associated with

depressive symptoms and adverse childhood

experiences. The results showed that students

who suffered from depressive symptoms were

more likely to commit suicide. Depression was a

common concern among college students even

before the pandemic. In the midst of the

pandemic, depression becomes more severe and

affects the lives of many college students around

the world, causing them to consider suicide [36].

The results of this study indicated that students

with symptoms of depression were more likely to

commit suicide. The results are consistent with

the meta-analysis conducted in China in 2019,

reported that a depressive symptom was

significantly associated with suicidal behavior

among Chinese college students [37].

Lastly, the present study extends existing

knowledge by demonstrating the association of

adverse childhood experiences increased the risk

of suicidal behavior among college students.

Adverse childhood experiences such as abuse

increased the risk for suicidal behavior. A

previous study conducted among Chinese college

students has shown that adverse childhood

experiences were associated with suicidal

ideation.

Despite the significant findings of this present

study, several limitations should be considered

for clinical interventions in suicidal behaviors

among college students in Pampanga,

Philippines. First, cross-sectional data were

collected at a single point in time, thus restricting

the ability to monitor changes in the relationship

between variables over time. The relationship

between these variables must be confirmed

through a longitudinal study. Also, mixed

methods research is recommended to explore the

in-depth the factors influencing suicidal behavior

among college students. Secondly, self-reported

questionnaires can lead to recall bias when data

is collected. Thirdly, the study was limited to

young adults in school settings and at one state

university, so its findings do not represent all

young adults. Using findings from this study to

apply to the entire Pampanga young adult

population should be done with caution.

Conclusion

An investigation was conducted to determine

whether college students in Pampanga engaged

in suicidal behavior, such as suicide ideation and

attempted suicide. In addition, an investigation

was conducted to determine the factors that

benefit or hinder these behaviors. A total of 443

college students, primarily females and in their

third year of studies, volunteered to participate in

the study. Approximately 24% of participants

reported suicidal thoughts, and 14% reported

plans for suicide. Among them, 9% attempted

suicide. Four independent variables, family

support, spiritual well-being, depressive

symptoms, and adverse childhood experiences,

were statistically significant. The strength of

family support was found to be a significant protective factor against suicide attempts.

Moreover, spiritual well-being helps prevent

suicide attempts. However, depression and

adverse childhood experiences were both found

to be risk factors for suicide attempts among

college students. And neither gender preference

nor age was significantly correlated with suicidal

behavior.

Based on the findings of the present study, some

recommendations are suggested: support from

family and spiritual well-being can help save the

lives of young people at risk of suicide,

according to the findings. An intervention that

integrates family support and spirituality may be

more effective for young adults at risk of suicidal

attempts. Additionally, treating depressive

symptoms and adverse childhood experiences

should also be integral to targeted mental health

interventions to reduce suicidal behavior.

Intervention strategies may be considered to

prevent adverse childhood experiences in the

Filipino family system.

Data Availability

The data that supports the findings of this study

are available from the corresponding author upon

reasonable request.

References

- Houser J, Oman KS. Evidence-based practice: An implementation guide for healthcare organizations. Jones & Bartlett Publishers; 2010.

[Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Preventing suicide Preventing suicide. WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data, 89. 2014.

[Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, Philippines. 2017: 2449.

- Paris J. Can we predict or prevent suicide?: An update. Preventive Medicine. 2021;152:106353.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

- Redaniel MT, Lebanan-Dalida MA, Gunnell D. Suicide in the Philippines: Time trend analysis (1974-2005) and literature review. BMC public health. 2011;11:536.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

- Kim AM, Jeon SW, Cho SJ, Shin YC, Park JH. Comparison of the factors for suicidal ideation and suicide attempt: A comprehensive examination of stress, view of life, mental health, and alcohol use. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2021;65:102844.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

- Jiang T, Nagy D, Rosellini AJ, Horváth-Puhó E, Keyes KM, et al. Suicide prediction among men and women with depression: A population-based study. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2021;142:275-282.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

- Page RM, West JH, Hall PC. Psychosocial distress and suicide ideation in Chinese and Philippine adolescents. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health. 2011;23(5):774-791.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

- Park S, Jang H. Correlations between suicide rates and the prevalence of suicide risk factors among Korean adolescents. Psychiatry Research. 2018;261:143-147.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

- Smith L, Shin JI, Carmichael C, Oh H, Jacob L, et al. Prevalence and correlates of multiple suicide attempts among adolescents aged 12â??15 years from 61 countries in Africa, Asia, and the Americas. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2021;144:45-53.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

- Kim AM. Factors associated with the suicide rates in Korea. Psychiatry Research. 2020;284:112745.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

- Ballester PL, Cardoso TD, Moreira FP, da Silva RA, Mondin TC, et al. 5-year incidence of suicide-risk in youth: A gradient tree boosting and SHAP study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2021;295:1049-1056.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

- Siu AM. Self-Harm and suicide among children and adolescents in Hong Kong: A review of prevalence, risk factors, and prevention strategies. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2019;64(6):S59-S64.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

- Choi KH, Wang SM, Yeon B, Suh SY, Oh Y, et al. Risk and protective factors predicting multiple suicide attempts. Psychiatry Research. 2013;210(3):957-961.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

- Rahman ME, Al Zubayer A, Bhuiyan MR, Jobe MC, Khan MK. Suicidal behaviors and suicide risk among Bangladeshi people during the COVID-19 pandemic: An online cross-sectional survey. Heliyon. 2021;7(2):e05937.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

- Wang Y, Feng Y, Han M, Duan Z, Wilson A, et al. Methods of attempted suicide and risk factors in LGBTQ+ youth. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2021;122:105352.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

- Fitzpatrick KM, Spialek ML. Suicide ideation and a post-disaster assessment of risk and protective factors among Hurricane Harvey survivors. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2020;277:681-687.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

- Kim YJ, Moon SS, Kim YK, Boyas J. Protective factors of suicide: Religiosity and parental monitoring. Children and Youth Services Review. 2020;114:105073.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Stack S. Contributing factors to suicide: Political, social, cultural and economic. Preventive Medicine. 2021;152:106498.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

- Kia H, MacKinnon KR, Abramovich A, Bonato S. Peer support as a protective factor against suicide in trans populations: A scoping review. Social Science & Medicine. 2021;279:114026.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

- Kleiman EM, Liu RT. Social support as a protective factor in suicide: Findings from two nationally representative samples. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2013;150(2):540-445.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

- Whitaker K, Shapiro VB, Shields JP. School-based protective factors related to suicide for lesbian, gay, and bisexual adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2016;58(1):63-68.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

- Å edivy NZ, Podlogar T, Kerr DC, De Leo D. Community social support as a protective factor against suicide: A gender-specific ecological study of 75 regions of 23 European countries. Health & Place. 2017;48:40-46.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

- Horwitz AG, Grupp-Phelan J, Brent D, Barney BJ, Casper TC, et al. Risk and protective factors for suicide among sexual minority youth seeking emergency medical services. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2021;279:274-281.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

- Chen YY, Yang CT, Pinkney E, Yip PS. The Age-Period-Cohort trends of suicide in Hong Kong and Taiwan, 1979-2018. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2021;295:587-593.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

- Chen Y, Zhu LJ, Fang ZM, Wu N, Du MX, et al. The association of suicidal ideation with family characteristics and social support of the first batch of students returning to a college during the COVID-19 epidemic period: A cross sectional study in China. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2021;12:653245.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

- Midea M, Kabamalan M. Percent of youth who, in the past week, â??oftenâ? felt the depressive symptoms from the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D) Scale: 2013 and 2021. 2022.

- Alvarez-Subiela X, Castellano-Tejedor C, Villar-Cabeza F, Vila-Grifoll M, Palao-Vidal D. Family factors related to suicidal behavior in adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022;19(16):9892.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

- Boyd DT, Quinn CR, Jones KV, Beer OW. Suicidal ideations and attempts within the family context: The role of parent support, bonding, and peer experiences with suicidal behaviors. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 2022;9(5):1740-1749.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

- Mathew A, Saradamma R, Krishnapillai V, Muthubeevi SB. Exploring the family factors associated with suicide attempts among adolescents and young adults: A qualitative study. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine. 2021;43(2):113-118.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

- Ibrahim N, Che Din N, Ahmad M, Amit N, Ghazali SE, et al.. The role of social support and spiritual wellbeing in predicting suicidal ideation among marginalized adolescents in Malaysia. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(Suppl 4):553.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

- Poorolajal J, Goudarzi M, Gohari-Ensaf F, Darvishi N. Relationship of religion with suicidal ideation, suicide plan, suicide attempt, and suicide death: A meta-analysis. Journal of Research in Health Sciences. 2022;22(1):e00537.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

- Leung CH, Pong HK. Cross-sectional study of the relationship between the spiritual wellbeing and psychological health among university students. PLoS One. 2021;16(4):e0249702.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

- Walsh F. Loss and resilience in the time of COVID-19: Meaning making, hope, and transcendence. Family Process. 2020;59(3):898-911.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

- Taliaferro LA, Rienzo BA, Pigg RM, Miller MD, Dodd VJ. Spiritual well-being and suicidal ideation among college students. Journal of American College Health. 2009;58(1):83-90.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

- Zhou SJ, Wang LL, Qi M, Yang XJ, Gao L, et al. Depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation in Chinese university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021;12:669833.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

- Wang YH, Shi ZT, Luo QY. Association of depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation among university students in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2017; 96(13):e6476.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pub Med]

Citation: Protective and Risk Factors of Suicidal Behavior among College Students in Pampanga, Philippines, Vol. 24(4) April,2023; 1-9.