Introduction

In December 2019 a new viral outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome, coronavirus-2 infection, occurred in Wuhan city, which later spread throughout China and other countries [1,2]. The current COVID-19 outbreak marks the third novel coronavirus emergence in the 21stcentury, after the 2003 SARS and the 2013 Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) [3]. On 11 March 2020, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19, a pandemic [4]. And since that the pandemic situation has been fluctuating, and the crisis has yet to be fully resolved. This virus has impacted not only lifestyles, the economy, and physical health but also the mental health of more people [5]. As with all communicable diseases, the COVID-19 outbreak has affected all individuals and communities in terms of their health [6]. This is more evident in Healthcare Workers (HCWs) who have engaged in the frontline in the fight against COVID-19. Everyone is a witness to the unprecedented situation caused by this pandemic which put the entire worldwide health system in difficulty. Because of the overwhelmed system, the HCWs engaged in the treatment of patients faced an extremely high risk of COVID-19 infection, thing which was also accompanied by psychological distress and symptoms of mental health problems when coping with the COVID-19 pandemic [7]. This is because mental health is easily vulnerable o temporary and long term psychological issues caused by unusual situations such as natural disasters or pandemics on the scale of COVID-19 for all of us. Cai, et al., in their study mention, that people who did not receive public health emergency treatment performed worse in social support, resilience, and mental health and were more likely to suffer from psychological distress and mental abnormalities such as interpersonal sensitivity and photic anxiety [8]. In the first months of this pandemic, the frontline healthcare workers were all the time under the fear and stress of being contaminated by the disease, being quarantined as a consequence of infection, the possibility that their family and friends maybe will be infected and caring for fellow workers as a patient. On the other hand, in the context of the pandemic crisis, the lack of protective measures, feelings of stigmatization, and rejection by others in their locality were also big problems that influence mental health problems among the healthcare workers on the front line Khan et al., in their study, had archived that high levels of depression, fear, anxiety, insomnia, and distress were the mostly psychological issues confronting the HCWs [9-12]. According to many studies, health care workers, mainly those on the front line, but not only are facing different mental health problems caused by the pandemic [13-16]. HCWs, who come close in contact with these patients when providing care are often left stricken with inadequate protections from contamination, high risks of infection, stress, fear, anxiety, depression, and poor sleep quality, which, in turn, are significantly associated with physical symptoms such as headache, lethargy, fatigue, etc. [17-19]. Bashirian, et al. study, showed that healthcare workers (physicians, radiologists, technicians, nurses, etc.) had remarkable cut off levels of depression, anxiety, and distress that varied due to demographic parameters, access to personal protective equipment, and the COVID-19 status, hence, their perceived threat to COVID-19 was relatively at the estimated level whereas, the perceived desired efficiency was not [20].

In addition, many studies have been performed in determining several risk factors associated with the mental health of healthcare workers, including symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic [21].

The results presented by Lai, et al., in one study conducted in China illustrated that 50.4% of healthcare workers suffered stress and 44.6% of those coping with anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic [22]. While according to Kang et al. other factors in terms of the demanding nature of their work, such as long working hours, risk of infection, and shortages of protective equipment, loneliness, physical fatigue, and separation from families were associated with the increase in adverse mental health outcomes among study subjects [23]. On the other hand, in our country, the only study that presented the level of anxiety and depression among healthcare workers was conducted by Kamberi, et al., In one study conducted in April-May, 2020 on 410 healthcare workers in Albania, mild levels of anxiety were expressed in 26.9% of participants while 7.2% of them expressed moderate levels, while 23.1% and 12.1% of participants expressed respectively mild and moderate depression levels [24].

This pandemic has rapidly changed society's functioning at many levels, suggesting that these data are not only needed swiftly but also with caution and scientific rigor [25]. For all those reasons we have undertaken this study to investigate the prevalence and associated risk factors of mental health situations among physicians and other medical employees in Albania.

Materials and Methods

Study design and study population and sampling

A cross sectional, descriptive study design was performed to investigate the mental health disorders among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, the relationships between stress, depression, anxiety, burnout, and COVID-19 related stress were also assessed.

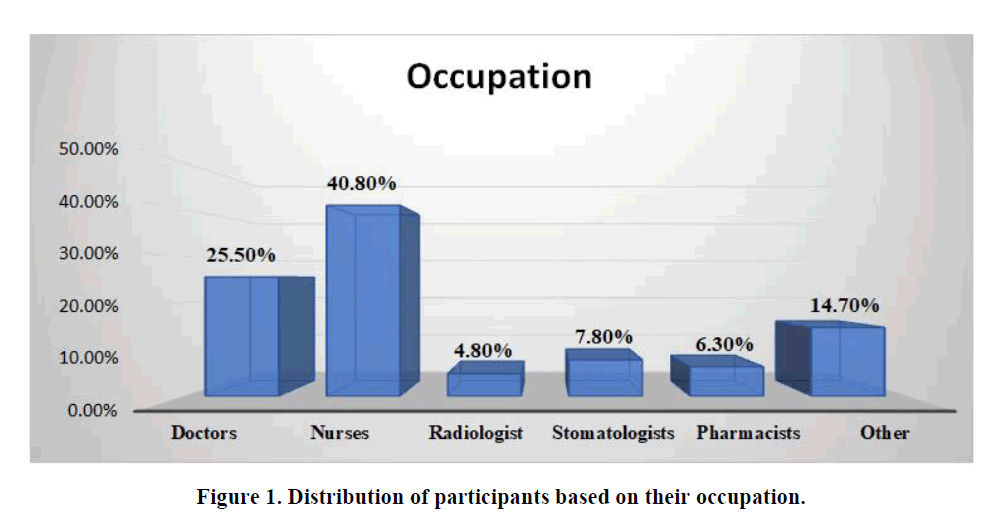

This survey recruited participants from different healthcare workers occupations. Out of 537 medical employees from public and private systems, nurses were the most predominant participants 40.8% in this study. Doctors were 25.5%, while radiologists, stomatologists, and pharmacists presented the lower number of participants with 4.8%. 7.8% and 6.3% respectively. For the other occupation, we have included support staff such as technicians, cleaners, security, and administrative that presented 14.7% of participants in this study (Figure 1).

The inclusion criterion included both males and females who were in the age range of ≥ 23– ≤ 60 years, were part of the healthcare workers on the front line of COVID-19 disease engaged in the treatment of patients and agreed to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria were all healthcare workers that were not engaged in the treatment of COVID-19 patients who did not agree to take part in the study.

Demographic data, working, and exposure to COVID-19 among HCWs

All healthcare staff was asked several questions about their personal information, including demographic characteristics, potential factors, and mental health problems. For the demographic characteristics data of participants in this study, we used a self-reported questionnaire which included data about gender, age, marital status, residence, living alone, working place, occupation, area of work, years of experience, the average working time during COVID-19, direct contact with COVID-19 patients, exposure to COVID-19, testing for COVID-19, quarantined, and any family member infected with COVID-19.

Measures

This survey was conducted from September 2020 to January 2021 time when the COVID-19 pandemic in Albania was at its peak. The study instruments consisted of a questionnaire comprising demographic characteristics, work details, and four tools including the Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), the fear of COVID-19 scale, the generalized anxiety disorder 7 item scale, and the patient health questionnaire 9.

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) was measured by 3 questions, which we adapted from DSM-5 criteria; the presence of work related trauma, presence of avoidance of relevant stimuli/hypervigilance, or re-experiencing symptoms, and impaired function. All criteria must be met for participants to be identified as having PTSD [26,27].

To assess the fear of Covid-19 we used the FCV-19’S questionnaire, in which we have a rating of questions with points from 0 to 4. Answers included “strongly disagree,” “disagree,” “neutral” “agree” and “strongly agree”. The minimum score possible for each question is 1, and the maximum is 5. A total score could be calculated by adding up each item’s score (ranging from 7 to 35) [28]. A higher score will be an indicator of a higher COVID-19 related fear

The General Anxiety Disorder 7 item scale (GAD-7) is one of the tools used to screen for anxiety or to measure its severity. The scores were interpreted as followed: normal (0-4); mild (5-9); moderate (10-14); and severe (15-21). The cut-point for having anxiety was five yielding sensitivity and specificity, 89% and 82% respectively to detect generalized anxiety disorder [29]. Depression was measured with Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). The scores were interpreted as follows: normal (0-6), mild (7-12), moderate (13-18), and severe (≥ 19) (30). As a PHQ-9 score ≥ 7 is 95% sensitive and 55% specific for a diagnosis of major depression, the cut point for having depression was seven. The total score is calculated by adding together the scores for the 9 questions. These scales have been used by several studies to screen mental health or to identify the mental well-being of a targeted population [30].

Table 1 presented Cronbach’s alpha value which we used to measure the internal consistency of a set of items to see how closely they are as a group. The Cronbach’s alpha in the PTSD scores section results in internal consistency of “acceptable” 0.712, FCV-19 scale in the internal consistency of “good” 0.832, GAD-7 scores in internal consistency of “good” 0.845 while the Cronbach’s alpha in the PHQ-9 score section results in the internal consistency of “good” 0.860 (Table 1).

Table 1. Results of Cronbach's alpha analysis.

|

Cronbach's alpha |

Cronbach's alpha based on standardized items |

N of items |

| Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) |

0.712 |

0.767 |

3 |

| Fear of Covid-19 (FCV-19 scale) |

0.832 |

0.839 |

10 |

| General Anxiety disorder 7 items scale (GAD-7) |

0.845 |

0.853 |

7 |

| Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) |

0.86 |

0.869 |

9 |

Statistical analysis data

Quantitative data analysis was performed using SPSS version 20.0. Descriptive statistics were used to explore ’HCWs’ characteristics and their mental health outcomes. The associations between the outcomes of mental health and variables were assessed by the Chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test, and independent sample t-tests. Binary logistic regression, followed by multiple logistic regression was used to calculate the odds ratios. Variables were included in the multivariable model if they have a p-value <0.05 in univariable analysis.

Results

Table 2 shows the demographic characteristics of healthcare workers. The average age in this study was 35.05 ± 12.13 Std, with an age range from 24 years as the minimum age to 66 years as the maximum age. The 30-39 age group represents the highest number of participants in this study with 52.1%, and the age ≥ 60 years old presents the lowest number of participants in this study with 4.1%. There was found a significant association between the age of participants χ2=11.9, the p-value=0.004. In this study, mostof the HCWs were women in 74.7%, while men were about 25.3% There was found a significant association between them χ2=15.3, the p-value=0.02.

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of healthcare workers.

| Variables |

Number of participants |

Percentage |

| Gender |

| Men |

136 |

25.30% |

| Women |

401 |

74.70% |

| Age |

| 24-29 years old |

59 |

11% |

| 30-39 years old |

280 |

52.10% |

| 40-49 years old |

104 |

19.40% |

| 50-59 years old |

72 |

13.40% |

| ≥ 60 years old |

22 |

4.10% |

| The place of residence |

| Urban |

413 |

76.90% |

| Rural |

124 |

23.10% |

| Marital status |

| Single never married |

130 |

24.20% |

| Single, divorced or widowed |

31 |

5.80% |

| In a relationship/married but living apart |

46 |

8.50% |

| In a relationship/married and cohabiting |

310 |

57.70% |

| I prefer not to say |

20 |

3.70% |

| Do you live alone? |

| Yes |

98 |

18.20% |

| No |

439 |

81.80% |

Most of the participants lived in urban 76.9% and only 23.1% lived in rural areas. There was not found a significant association regarding the living are of participants for χ2=1.94 p-value=0.059.

Information related to their current marital status; the predominant part of the HCWs resulted in a relationship/married in 57.7%. In this case there was found a significant correlation for χ2=21.5, p-value= 0.0003.

Table 3 shows data about the working and exposure to COVID-19 among HCWs. Regarding the working place, most of the participants work in the public sector 75,5% (405/537) while 19% (102/537) are in the private sector. Only 5.5% (30/537) of the healthcare workers were part of public-private partnerships. A significant association was found for the workplace of health medical staff p-value of ˂0.05. Healthcare employees from Tirana and Durres, presented the higher number of participants 60.7%. Thus, HCWs from Tirana were 35.20% of participants, from Durres were 25.50% of participants, from Elbasan 18.10%, from Fier 9.7%, and others (including HWCs from other cities) were 11.5% of participants. There was found a significant association for cities where participants work for χ2=3.51 p-value of ˂0.05. Any one of the HWCs that agreed to be part of this survey was asked about their experience (years) in the medical field. Most of the HWCs 30.5% had 6-10 years of experience, in second place are HWCs with 11-15 years of experience, and in third place are HWCs with 16-20 years of experience. HWCs with 1-5 years of experience were 12.5% of participants while HWCs with more than 21 years of experience presented a small number of participants. As a consequence of the pandemic, more than three-four of the participants were forced to work long hours in their workplaces. In this survey, 76ths. 4% of HWCs had reported thatworked more than 8 hours per day, while 23.6% worked ≤ 8 hours per day. Related to exposure to COVID-19, 86.6% of participants referred that were exposed to COVID-19 and 13.2% referred that were not. Furthermore, 80.8% of HWCs had been referred were in direct contact with COVID-19 patients, and 19.2% were not. More than 95.3% were tested for COVID-19 and only 4.7% were not tested. About 67.4% of participants referred that were quarantined were resulted positive for COVID or/and had almost one member of a family infected with COVID-19, while 32.6% have not (Table 3).

Table 3. Data about the working and exposure to COVID-19

| Variables |

Number of participants |

Percentage |

| Working place |

| Public |

405 |

75.50% |

| Private |

102 |

19% |

| Both |

30 |

5.50% |

| Area of work |

| Tirana |

189 |

35.20% |

| Durres |

137 |

25.50% |

| Elbasan |

97 |

18.10% |

| Fier |

52 |

9.70% |

| Others |

62 |

11.50% |

| How many years of experience do you have working as an HWC? |

| 1-5 years |

67 |

12.50% |

| 6-10 years |

164 |

30.50% |

| 11-15 years |

123 |

22.90% |

| 16-20 years |

88 |

16.40% |

| 21-25 years |

45 |

8.40% |

| 26-30 years |

31 |

5.80% |

| >30 years |

19 |

3.50% |

| The average working time during COVID-19 |

| ≤ 8 hours per day |

127 |

23.60% |

| >8 hours per day |

410 |

76.40% |

| Exposure to COVID-19, |

|

|

| No |

71 |

13.20% |

| Yes |

466 |

86.80% |

| Direct contact with COVID-19 patients |

| No |

103 |

19.20% |

| Yes |

434 |

80.80% |

| Testing for COVID-19 |

| No |

25 |

4.70% |

| Yes |

512 |

95.30% |

| Quarantined, and any family member infected with COVID-19 |

| No |

175 |

32.60% |

| Yes |

362 |

67.40% |

Table 4 shows the burden of mental health disorders among healthcare workers. Stress and Fear were the most affected mental health among healthcare employees with 67.2% and 82.3% respectively. Anxiety was referred in 33.3% of participants while depression in 23.4%. Most of the medical employees appeared with symptoms of mild depression 74 (58.7%), whereas related to the severity of anxiety, 75 (41.9%) appeared with moderate to severe symptoms. Nurses and medical doctors were significantly more likely to report depressive symptoms compared to other medical employees χ2=85.2, 95% CI, a p-valueof 0.03 than radiologists, stomatologists, and pharmacists.

Table 4. The burden of mental health disorders among healthcare workers.

| Variables |

Doctors |

Nurses |

Radiologists |

Stomatologists |

Pharmacists |

Others |

| Stress PTSD |

Yes |

98 |

167 |

15 |

13 |

11 |

56 |

| Fear FCV-19 |

Yes |

102 |

201 |

19 |

30 |

23 |

67 |

| Anxiety GAD-7 (≥ 5) |

Yes |

42 |

84 |

10 |

9 |

6 |

28 |

| Depression PHQ-9 (≥ 7) |

Yes |

35 |

42 |

9 |

13 |

7 |

20 |

Female participants show a higher score for mental health disorders, particularly for fear, stress, and anxiety compared to males p<0.05, while medical employees who work in Tirana had a higher significant score than those living in other regions p<0.05. Furthermore, the younger age groups ≤ 40 years and >55 were more prone to report likely fair, stress, and depressive symptoms compared to other ages (p-value<0.05). Furthermore, healthcare workers with an average working time during COVID-19 ≥ 8 hours per day with exposure to COVID-19 or direct contact with COVID-19 patients were more likely to have big problems with mental health disorders. (p-value<0.05). Fear, stress, and anxiety were the most predominant health problems among HWCS. Table 5 shows the multivariate analyses of risk factor associated with PTSD, fear, anxiety, and depression among HCWs.

Table 5. Odds ratios from multivariable analysis of the associated factors of PTSD, fear, anxiety, and depression among HCWs.

| p-value |

PTSD |

FCV-19 |

GAD-7

|

PHQ-9 |

| Odds ratio |

95%CI |

p-value |

Odds ratio |

95%CI |

p-value |

Odds ratio |

95%CI |

p-value |

Odds ratio |

95%CI |

p-value |

| Gender |

| Men |

1 |

Reference |

|

1 |

Reference |

|

1 |

Reference |

|

1 |

Reference |

|

| Women |

1.52 |

0.79-2.34 |

0.04 |

1.05 |

0.50-2.12 |

0.02 |

1.81 |

0.97-3.19 |

0.035 |

0.98 |

0.59-1.70 |

0.06 |

| Age, year, mean (SD) |

2.37 |

1.42-4.58 |

0.01 |

1.91 |

1.47-4.08 |

0.04 |

1.23 |

0.71-2.43 |

0.02 |

2.28 |

0.84-3.39 |

0.049 |

| The place of residence |

| Urban |

1 |

Reference |

|

1 |

Reference |

|

1 |

Reference |

|

1 |

Reference |

|

| Rural |

0.89 |

0.43-1.27 |

0.07 |

43 |

0.01-0.85 |

0.7 |

0.67 |

0.04-0.91 |

0.4 |

0.8 |

0.52-1.30 |

0.1 |

| Marital status |

| Single |

1 |

Reference |

|

1 |

Reference |

|

1 |

Reference |

|

1 |

Reference |

|

| In a relationship/married |

3.45 |

2.01-7.89 |

<0.0001 |

1.17 |

0.76-2.38 |

0.01 |

1.7 |

0.64-2.91 |

0.003 |

0.9 |

0.32-1.30 |

0.37 |

| Do you live alone? |

| Yes |

1 |

Reference |

|

1 |

Reference |

|

1 |

Reference |

|

1 |

Reference |

|

| No |

3.27 |

1.83-9.57 |

<0.0001 |

2.73 |

1.12-5.70 |

0.003 |

0.45 |

0.09-1.20 |

0.8 |

1.11 |

0.49-1.97 |

0.04 |

| Working place |

| Public |

2.52 |

1.18-4.37 |

0.006 |

1.81 |

1.00-3.22 |

0.02 |

1.73 |

0.80-2.69 |

0.004 |

2.49 |

1.59-3.72 |

0.0001 |

| Private |

1.84 |

1.09-2.64 |

0.02 |

2.57 |

0.83-4.61 |

0.0002 |

0.97 |

0.42-1.64 |

0.07 |

1.36 |

0.73-2.54 |

0.002 |

| Both |

1 |

Reference |

|

1 |

Reference |

|

1 |

Reference |

|

1 |

Reference |

|

| Area of work |

| Tirana |

1.53 |

0.95-2.08 |

0.02 |

2.18 |

1.13-5.72 |

0.001 |

1.46 |

0.97-2.81 |

0.03 |

0.89 |

0.52-1.61 |

0.091 |

| Others |

1 |

Reference |

|

1 |

Reference |

|

1 |

Reference |

|

1 |

Reference |

|

| Years of experience as an HWC? |

| 1-5 years |

1.75 |

1.01-2.34 |

0.004 |

1.28 |

0.42-2.61 |

0.001 |

0.37 |

0.00-1.12 |

0.71 |

0.48 |

0.04-0.90 |

0.7 |

| 6-10 years |

1.37 |

0.79-2.64 |

0.043 |

1.52 |

0.49-3-42 |

0.03 |

1.82 |

0.74-2.67 |

0.008 |

1.38 |

0.92-1.86 |

0.03 |

| 11-15 years |

0.2 |

0.00-0.54 |

0.31 |

0.4 |

0.00-0.91 |

0.8 |

1.08 |

0.75-1.68 |

0.04 |

0.5 |

0.01-1.06 |

0.97 |

| 16-20 years |

0.64 |

0.18-0.85 |

0.7 |

0.67 |

0.03-1.69 |

0.75 |

0.37 |

0.02-1.42 |

0.6 |

1.06 |

0.23-2.04 |

0.043 |

| >20 years |

1 |

Reference |

|

1 |

Reference |

|

1 |

Reference |

|

1 |

Reference |

|

| The average working time during COVID-19 |

| ≤ 8 hours per day |

1 |

Reference |

|

1 |

Reference |

|

1 |

Reference |

|

1 |

Reference |

|

| >8 hours per day |

1.08 |

0.37-1.86 |

0.08 |

1.73 |

0.82-2.68 |

0.01 |

1.2 |

0.61-1.85 |

0.02 |

1.38 |

0.73-2.08 |

0.04 |

| Exposure to COVID-19 |

| No |

1 |

Reference |

|

1 |

Reference |

|

1 |

Reference |

|

1 |

Reference |

|

| Yes |

2.42 |

0.94-8.65 |

0.0009 |

1.67 |

0.75-3.84 |

0.007 |

1.51 |

1.08-3.05 |

0.005 |

1.28 |

0.84-2.37 |

0.02 |

| Direct contact with COVID-19 patients |

| No |

1 |

Reference |

|

1 |

Reference |

|

1 |

Reference |

|

1 |

Reference |

|

| Yes |

3.54 |

2.18-11.4 |

<0.0001 |

2.67 |

1.42-5.75 |

0.001 |

2.22 |

1.00-3.84 |

0.005 |

1.74 |

112-2.51 |

0.03 |

| Quarantined, and any family member infected with COVID-19 |

| No |

1 |

Reference |

|

1 |

Reference |

|

1 |

Reference |

|

1 |

Reference |

|

| Yes |

0.7 |

0.34-1.68 |

0.1 |

1.5 |

0.81-2.34 |

0.7 |

1.68 |

0.79-2.81 |

0.04 |

1.24 |

1.04-4.90 |

0.002 |

Discussion

Before 2020, mental disorders were the leading causes of the global health related burden, whereas depressive and anxiety disorders were the leading contributors to this burden. The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic has created an environment where many determinants of poor mental health are exacerbated [31]. World Health Organization in one scientific brief in 2022, reported that the COVID-19 pandemic has led to a 27.6% increase (95% Uncertainty Interval (UI): 25.1–30.3) in cases of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) and a 25.6% increase (95% UI: 23.2–28.0) in cases of Anxiety Disorders (AD) worldwide in 2020. Furthermore, the greatest increases in MDD and AD were found in places highly affected by COVID-19, as indicated by decreased human mobility and daily COVID-19 infection rates [32]. More studies conducted in different states of Europe (Italy, Turkey, and Spain) or in China and Iran reported a higher pooled prevalence of mental health disorders among healthcare workers than the general population [33-37].

To our knowledge, this is the second study to investigate health disorders among HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic in Albania. We have investigated different occupations of healthcare workers that were engaged in the treatment of patients during the second wave of the pandemic, at the peak time of the covid-19 disease, the time when the number of daily infections and loss of life was relatively high. Despite the mild to moderate levels of anxiety (26.9% and 7.2%) and depression (23.1% and 12.1%) expressed in healthcare workers in Albania during the early phase of the pandemic found in a previous study, the findings of this study reported the higher mental health disorders rates such as fear (82.3%), stress (67.2%|), depression (23.4%), and anxiety (33.3%), among health workers.

Due to the close contact and/or engagement with patients in the treatment of COVID-19, mental health disorders were encountered mostly in doctors and nurses, compared to other categories included in this study. Furthermore, being female and being a nurse were significantly associated with severe symptoms of fear, stress, depression, and anxiety.

Our finding is similar to other studies conducted in 2020 by Lai, et al., and Tan, et al., in which nurses experienced more psychological symptoms associated with caring for patients with COVID-19 [38,39].

Zhang, et al., in their study mention that living in rural areas, being female, and being at risk of contact with COVID-19 patients were the most common risk factors for more of mental health disorders like anxiety and depression (p<0.01 or 0.05) [40]. But the findings in our study related to the living area were in contrast with the previous study. Thus, HWCs that live in rural or urban areas do not appear a significant association with any of the mental health disorders that we analyzed. While as we highlighted before, being a female and being in close contact or engaged with COVID-19 positive patients, appeared a highly significant association with almost all mental health disorders analyzed. Females resulted in high significance for fear, stress, and anxiety with the p-value <0.05 while HWCs being in closecontact with patients resulted in highsignificance for fear, stress, anxiety, anddepression with the p-value <0.05. In addition,many studies have reported the impact of some risk factors (such as age, marital status, living alone, working place (private vs. public) experience in a medical workplace or years of experience with treatment of patients, and longer working hours in a clinical environment during COVID-19) that may contribute to psychological distress among healthcare workers [41-46]. Our study showed that younger age, married status, living with others, fewer years of experience in a clinical environment, and longer working hours were persistent risk factors for mental health disorders, regardless of the time of the second wave of the pandemic in our country. Those specific findings need further research with the inclusion of a higher number of health workers to understand if there is a cultural aspect related to this and whether the level of knowledge and education plays a role in the anxiety level of different HCWs.

Conclusion

This study reports a high level of fair and stress and mild to moderate burdens of depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic among physicians and other medical employees in Albania. Females, the younger age groups ≤ 40 years and >55, and the nursing profession were the most affected by mental health problems. Based logistic regression revealed that gender and of participants were significantly associated with moderate and severe anxiety levels, p-value <0.05. A significant relationship was found between some of the variables of risk factors and mental health problems. Thus, a significant relationship was observed for age, marital status, specialty, and workplace of medical staff. In all cases, the p-value was <0.05. Furthermore, studies with a large sample size to include all health medical staff nationwide need to identify and evaluate mental health among medical staff in Albania.

Recommendation

Considering the findings, further studies are recommended at the country level to explore the mental health condition of health workers staff that is in the first line of treatment of patients during the pandemic in order to develop evidence based strategies and to reduce the degree of risk for developing mental problems in this category.

We also recommend applying for prevention programs in four main categories such as; "social/structural support", "better work environment", more efficient provision of "communication/information", as well as "mental health support “, which will come to the aid of health workers staff, improving the mental load on these individuals during the pandemic.

All four of these categories should be applied in interaction with each other as medical staff is the category that poses a high risk for mental health problems during the pandemic being exposed on the front line.

Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the university Alexander Xhuvani ethical committee. Due to technical difficulties caused by the pandemic situation Ethical clearance was obtained from the rector of the university Alexander Xhuvani, Elbasan, Albania (issues date 01/09/2020). All Healthcare workers participants in this survey were informed through online communication with one of the platforms WhatsApp and Messenger. All ethical guidelines based on Albanian Low no.9887, issue date 10/03/2008, amended for Low No.48/2012, amended in Low No. 120/2014 “On the protection of personal data” were strictly respected. Furthermore, during this study, we followed the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975, as revised in 2008. Before enrollment, the researcher explained the purpose of the study. All HCWs were informed that participation in the study was voluntary, participants could withdraw at any moment and all the data collected will be used only for the current study. No personal data were recorded, and all questionnaires were completed anonymously. We warrant that all ethical guidelines for medical research were strictly respected.

Competing Interests

Not applicable

Authors' Contributions

L.Ramasaco and E. Abazaj both were involvedin the conception and design of the study, L.Ramasaco, E. Abazaj, B. Brati, and L. Shundi:we’re part of the data collection, and analyzedthe data. E. Abazaj analyzed the data (statisticalanalyses) and made critical revisions. Allresearchers drafted the manuscript and approvedthe final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Firstly, I would like to acknowledge all our colleagues who were on the front line of the COVID-19 pandemic and find the time to be participants in this survey who were part of this study. Secondly, I would like to acknowledge my co-authors for their support, assistance, and contribution during the preparation of this paper. And finally, the acknowledgments go to the head of the university “Alexander Xhuvani” Elbasan city, for his permission and assistance in finalizing this paper. Without all contributors’ help, this work would be difficult to accomplish.

Conflict of Interest

The researchers declared that there is no financial or non-financial conflict of interest. All the data presented in this paper have been collected on our part and the participant’s anonymity is preserved.

References

- Raba AA, Abubakar A, Elgenaidi IS, Daoud A. Novel coronavirus infection (COVID-19) in children younger than one year: A systematic review of symptoms, management, and outcomes. Acta Paediatr. 2020; 109 (10): 1948-1955.

[Crossref][Googlesholar][Pubmed]

- Paules CI, Marston HD, Fauci AS. Coronavirus Infections More than Just the Common Cold. JAMA. 2020; 323(8):707-708.

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- Xu C, Wang J, Wang L, Cao C. Spatial pattern of severe acute respiratory syndrome in-out flow in 2003 in mainland China. BMC Infect Dis. 2014; 14:721.

[Crossed][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Update. World Health Organization. 2021.

- Chinvararak C, Kerdcharoen N, Pruttithavorn W, Polruamngern N, Asawaroekwisoot T, et al. Mental health among healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic in Thailand. PLoS ONE. 2022; 17(5):0268704.

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- Cincidda C, Pizzoli S, Oliveri S, Pravettoni G. Regulation strategies during Covid-19 quarantine: the mediating effect of worry on the links between coping strategies and anxiety. Eur Rev Appl Psychol. 2021; 100671.

[Crossref][Googlescholar]

- Chew NWS, Lee GKH, Tan BYQ, Jing M, Goh Y, et al. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during the COVID-19 outbreak. Brain Behav Immun. 2020; 88: 559–565.

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- Cai W, Lian B, Song X, Hou T, Deng G, et al. A cross sectional study on mental health among health care workers during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019. Asian J Psychiatr 2020; 51: 102111.

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- Mohsin SF, Agwan MA, Shaikh S, Alsuwaydani ZA, Al Suwaydani SA. COVID-19: Fear and Anxiety among Healthcare Workers in Saudi Arabia. A Cross-Sectional Study Inquiry. 2021; 58.

[Crossref [Pubmed]

- Temsah M, Al-Sohime F, Alamro N. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health care workers in a MERS-CoV endemic country. J Infect Public Health. 2020; 13(6):877-882.

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- Sakib N, Akter T, Zohra F, Bhuiyan AKMI, Mamun MA, et al. Fear of COVID-19 and depression: a comparative study among the general population and healthcare professionals during COVID-19 pandemic crisis in Bangladesh. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2021;1-17.

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- Khan YH, Mallhi TH, Alotaibi NH, Alzarea AI. Work related stress factors among healthcare professionals during COVID-19 pandemic; a call for immediate action. Hosp Pract. 2020; 48(5):244-245.

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- Nguyen TK, Tran NK, Bui TT, Tran LT. Mental Health Problems Among Front-Line Healthcare Workers Caring for COVID-19 Patients in Vietnam: A Mixed Methods Study. Front Psychol. 2022; 13:858677.

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- Shah J, Monroe-Wise A, Talib Z. Mental health disorders among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional survey from three major hospitals in Kenya. BMJ Open. 2021; 11: 050316.

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- Khanal P, Devkota N, Dahal M, Paudel K, Joshi D. Mental health impacts among health workers during COVID-19 in a low resource setting: a cross-sectional survey from Nepal. Global Health. 2020; 16:89.

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- de Kock JH, Latham HA, Leslie SJ, Grindle M, Munoz SA, et al. A rapid review of the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of healthcare workers: implications for supporting psychological well-being. BMC Public Health. 2021; 21:104.

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- Vindegaard N, Benros ME. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: Systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav Immun. 2020; 89: 531-542.

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- Chew NW, Lee GK, Tan BY, Jing M, Goh Y, et al. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain Behav Immun 2020; 88: 559-65.

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- Jaber MJ, AlBashaireh AM, AlShatarat MH, Alqudah OA. Stress, Depression, Anxiety, and Burnout among Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-sectional Study in a Tertiary Centre. Open Nur J. 2022; 16.

[Crossref][Googlescholar]

- Bashirian S, Jenabi E, Khazaei S, Barati M, Karimi-Shahanjarini A, et al. Factors associated with preventive behaviors of COVID-19 among hospital staff in Iran in 2020: An application of the Protection Motivation Theory. J Hosp Infect. 2020; 105(3): 430-433.

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, Giannakoulis VG, Papoutsi E, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2020; 88: 901–907.

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020; 3: 203976.

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- Kang L, Li Y, Hu S, Chen M, Yang C, et al. The mental health of medical workers in Wuhan, China dealing with the 2019 novel coronavirus. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020; 7: 14.

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- Kamberi F, Sinaj E, Jaho J, Subashi B, Sinanaj G, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health, risk perception, and coping strategies among health care workers in Albania evidence that needs attention. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2021; 12:10082.

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- Holmes EA, O'Connor RC, Perry VH, Tracey I. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020; 7(6):547–560.

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, Witte TK, Domino JL. The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. J Trauma Stress. 2015; 28:489–498.

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092–1097.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001; 16:606–613.

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- Santomauro DF, Mantilla Herrera AM, Shadid J, Zheng P, Ashbaugh C, et al. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021; 398(10312):1700–1712.

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- World Health Organization. Mental Health and COVID-19: Early evidence of the pandemic’s impact: Scientific brief, 2 March 2022. WHO.

- Wang C, Pan R, Wan X. A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87: 132-133.

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- Yang Y, Lu L, Chen T, Ye S, Kelifa MO, et al. Mental Health and Their Associated Predictors During the Epidemic Peak of COVID-19. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2021:14 221–231.

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- Moccia L, Janiri D, Pepe M, Dattoli L, Molinaro M, et al. Affective temperament, attachment style, and the psychological impact of the COVID-19 outbreak: an early report on the Italian general population. Brain Behav Immun. 2020; 87:75–79.

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- Luo M, Guo L, Yu M, Jiang W, Wang H. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020; 291:113190.

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- Lu YC, Shu BC, Chang YY, Lung FW. The mental health of hospital workers dealing with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Psychother Psychosom. 2006; 75(6):370–375.

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open 2020; 3: 203976

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- Tan BYQ, Chew NWS, Lee GKH. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health care workers in Singapore. Ann Intern Med. 2020; 173:317–320

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- Zhang WR, Wang K, Yin L, Zhao WF, Xue Q, et al. Mental Health and Psychosocial Problems of Medical Health Workers during the COVID-19 Epidemic in China. Psychother Psychosom. 2020;89(4):242-250.

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- Hwang TJ, Rabheru K, Peisah C, Reichman W, Ikeda M. Loneliness and social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int Psychogeriatr. 2020; 32(10):1217-1220.

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- Yassin, A, Al-Mistarehi AH, Soudah O, Karasneh R, Al-Azzam S, et al. Trends of Prevalence Estimates and Risk Factors of Depressive Symptoms among Healthcare Workers Over One Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Clin Pract Epidemiology Ment Health. 2022; 18 (3):1745-0179/22.

[Crossref][Googlescholar]

- Andersen AJ, Mary-Krause M, Bustamante JJH, Héron M, El Aarbaoui T, et al. Symptoms of anxiety/depression during the COVID-19 pandemic and associated lockdown in the community: longitudinal data from the TEMPO cohort in France. BMC Psychiatry. 2021; 21(1): 381.

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- Rondung E, Leiler A, Meurling J, Bjarta A. Symptoms of depression and anxiety during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in Sweden. Front Public Heal. 2021; 9:562437.

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- Ettman CK, Abdalla SM, Cohen GH, Sampson L, Vivier PM, et al. Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw Open 2020; 3(9): 2019686.

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- Han X, Chen S, Bi K, Yang Z, Sun P. Depression following COVID-19 lockdown in severely, moderately, and mildly impacted areas in China. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12: 596872.

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- Ayuso-Mateos JL, Morillo D, Haro JM, Olaya B, Lara E, et al. Changes in depression and suicidal ideation under severe lockdown restrictions during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain: A longitudinal study in the general population. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2021; 30: 49.

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]

- Andersen LH, Fallesen P, Bruckner TA. Risk of stress/depression and functional impairment in Denmark immediately following a COVID-19 shutdown. BMC Public Health. 2021; 21(1): 984.

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Pubmed]