Introduction

Health care professionals the new coronavirus

epidemic caused a sudden crisis in the world’s

public health in late 2019, killing more than

838,000 people worldwide by August 30, 2020

[1]. The emergence of COVID-19 has changed

people’s living conditions by causing travel

restrictions, fear of transmission, fear of infection,

fear of losing loved ones, closure of jobs and schools, and the devastating psychological effects

of quarantine, such as depression, emotional

changes, and individual and social anxiety

[2]. In the meantime, nurses and health care

workers are at the forefront of the fight against

infectious diseases and COVID-19 and are more

susceptible to the disease. The high mortality

rate of hospitalized patients in COVID-19 wards,

communication problems, lack of support, and

lack of visiting time for COVID-19 patients have created a stressful condition for the nurses

in coronavirus care wards [3]. Therefore, health

professionals and in particular nurses often face a

variety of stressful conditions in life, including the

challenges of personal life, the nature of their job

that requires a lot of standing and concentration,

commitment to patient care, and working with

patients that need help [4].

They are constantly exposed to various stressors

that will have devastating effects on their job

performance in the long run [5]. Murphy has

defined job performance as a function of an

individual’s performance in doing specific

tasks, which includes a list of standard jobs [6].

The core of job performance depends on job

demands, organizational goals and missions,

and the organization’s beliefs about behaviors

that are evaluated more frequently [7]. As far

as nurses are concerned, job performance is

defined as an effective factor in the ability to

achieve occupational goals in accordance with job

standards. As a powerful arm of the health care

system and a solid pillar of patient care, nurses

play an important role in care departments and

affect every aspect of hospital performance. Job

performance results from the combination three

components: Expertise, effort, and the nature

of working conditions [8]. Expertise refers to

knowledge, ability, and scientific and professional

competence of an employee in a particular field;

effort includes a degree of internal and external

motivation that makes a person excel in doing

work; and the nature of working conditions

includes a degree of compliance with the

conditions in facilitating employee productivity

[9].

In the case of nurses, job performance is defined

as an effective factor in performing tasks and

responsibilities related to direct patient care, and

patient satisfaction and their mental and physical

health are greatly affected by the performance

of nurses [10]. The results of a study conducted

in Urmia indicated that an increase in the effect

of COVID-19 led to the decrease of the nurse’s

job performance by 20% [11]. In this condition,

health care providers caring for clients face daily

situations that might have adverse effects on the

quality of their care [4]. Given that psychological

stress affects job performance, social support can

act as a contributor to coping with stress, and this

is more appropriate for nurses trying to improve

their performance to a desired level [7]. Social

support is defined as the actual or perceived useful behaviors available from others [12]. It can be

considered as support that a person receives from

family, friends, and the organization, and has a

psychological dynamic that helps the person in

emotional, physical, and cognitive aspects. Social

support is studied as either perceived or received

[13].

Perceived social support focuses on the individual’s

cognitive assessment of his/her environment

and his/her level of confidence that help and

support will be available if required [14]. In the

nursing profession, social support is considered

as an occupational source. Social support from

colleagues not only reduces negative effects of

job stressors, but also guarantees that the work is

done the best and the occupational goals will be

achieved. In addition, social support from friends

meets the person’s basic needs, such as the need

to belong. Thus, social support is an incentive for

work interaction through a motivational process

[15]. Supportive work environments are the

most important factor in creating job satisfaction

for nurses, and enjoying social support affects

patient treatment, employees’ job satisfaction,

and recruitment and retention in the organization.

Therefore, a work environment with a high level

of social support will reduce job stress and retain

the nurses in the organization [16].

Perceived social support is a combination

of the three elements including emotion,

acknowledgment, and help. Emotion means

expressing love and affection; acknowledgment

refers to the awareness of appropriate behaviors

and feedbacks; and help means direct assistance

in getting things done. Thus, one of the

characteristics of the people relatively resistant

to stressful events is having social support. Social

support systems can mitigate negative effects

of stress on mental health; therefore, having to

support patients, nurses themselves need support

systems [17]. Sarafino believes that social support

from friends, family, and other people leads to

reduced psychological stress in individuals and

thus affects their mental health [18]. According to

the theory of social support barrier-making, people

enjoying high social support consider problems

less stressful and may have a person or people

who can provide solutions to their problems and

give them encouragement and hope. Accordingly,

social support can be used as a barrier to negative

effects of stress and have an inverse relationship

with the perception of stress and burnout [19].

Therefore, providing social support inside and outside the workplace can play an effective role

in the health and well-being of nurses, improve

employee productivity, and reduce stress in the

face of challenges and problems [20]. A study of

a group of nurses in the United States, the United

Kingdom, and Canada found that perceived

social support from co-workers increased job

performance and reduced job stress in nurses [16].

Another effect of the spread of viral diseases,

including COVID-19 that has affected the world

at various levels, is stress and work pressure that

causes dissatisfaction with the job and may lead to

job burnout [11]. Job burnout is a psychological

syndrome and a long-term response to chronic

stress in the workplace. It was first described by

Maslach, and its three main and distinct dimensions

including exhaustion, depersonalization, and

personal inadequacy were then introduced for job

evaluation [21,22]. The results of a meta-analysis

by Chemali et al., showed that the prevalence of

job burnout among physicians, nurses, and other

medical staff in the Middle East hospitals was

about 40% to 60%. Job burnout is on the rise

due to the high workload during the coronavirus

pandemic [23,24].

Emotional exhaustion is considered as one of the

components of job burnout. Nurses are known as

one of the groups at risk of emotional exhaustion

due to the nature, severity, and variety of the

stressors associated with their professional tasks

[25]. Emotional exhaustions are defined as the

feeling of extremely lacking emotional and physical

resources [26]. It is associated with the concepts

of stress, anxiety, physical tiredness, insomnia

[27]. Research has shown that job relationships

that lack support and trust may increase the risk of

burnout. When job relationships are positive and

employees experience high levels of social support,

job interactions improve as well. Besides, when

individuals are supported by their workgroups,

job resources (human resources, job capacities)

are enriched, and job resources (capacities) can

effectively reduce the prevalence of burnout [28].

Therefore, like useful information and emotional

support, social support is an important source for

employees to cope with daily stressors and thus

improve their well-being [29].

Subjective well-being is another problem with

nurse’s health. It is described as a set of experiences

including emotional responses, satisfaction range, and overall judgment of life satisfaction,

and deals with individual’s evaluation of their

lives and mental measurement of satisfaction

or dissatisfaction [30]. Subjective well-being is

associated with positive and negative memories

as well as emotional reactions to life events.

It is in fact a term used to measure people’s

satisfaction, happiness, and experience of quality

of life. The experience includes cognitive and

emotional perception and evaluation of life [31].

The emotional dimension refers to having positive

emotions (pleasure, euphoria, happiness) and

negative emotions (feelings of guilt, fear, anger)

as well as emotions, and the cognitive dimension

refers to a cognitive assessment of life satisfaction

that measures a person’s positive emotions and

excitement from different aspects of life [13].

Employees who are satisfied with their job and

experience more positive emotions have a high

level of subjective well-being. On the other hand,

employees who do not have subjective well-being

often suffer from job burnout. The importance

of subjective well-being in an organization can

be found out from positive results such as job

performance, reduced absenteeism, and job

satisfaction [32].

Social environments, including interpersonal

relationships and social support from others,

play a key role in shaping people’s prosperity

and satisfaction with life. The results of a study

showed that social support improved well-being

by affecting emotions, cognitions, and behaviors

in a way that it promoted positive effects [33].

Regarding what was stated above, it seems really

important to address the factors affecting the

performance of nurses, and since nursing is one

of the highly important occupations in the society

and nurses spend some part of their lives in close

contact with patients, and due to the fact that

optimal job performance guarantees the health

and recovery of many patients in the community,

identifying the factors affecting their performance

and trying to promote such factors is of particular

importance. Therefore, considering the everincreasing

spread of the coronavirus and the

excessive exhaustion of medical staff, the present

study aimed to answer the question whether

perceived social support and job performance had

a relationship with the mediating role of emotional

exhaustion and subjective well-being of nurses.

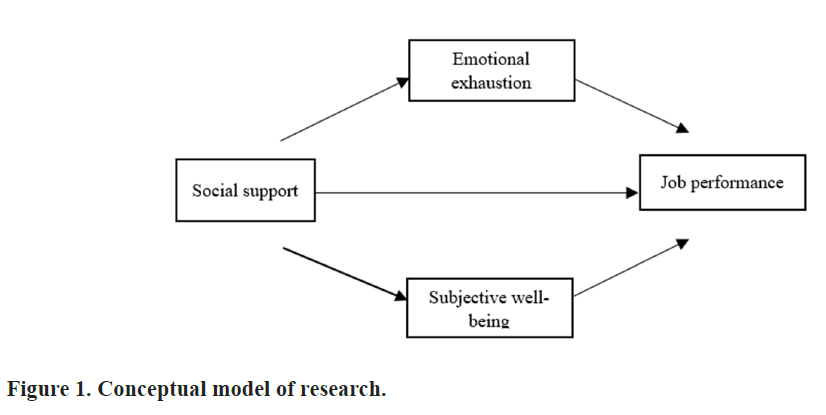

The conceptual model of research is shown in Figure 1.

Materials and Methods

The present study is an applied descriptivecorrelational

research. An electronic questionnaire

was used to collect the information in this study.

To this end, to this end, once the approval of the

hospital’s ethics committees was obtained and

coordination with the hospital authorities, the

questionnaire was designed online and its link

was provided to the people who were willing to

participate in the study. The statistical population

included all the nurses in Kerman hospitals in

2021. Five hospitals were randomly selected from

among the public hospitals of Kerman. The sample

size was considered 300 with regard to the number

of the study variables, but due to possible drops, 21

more individuals (a total of 321 nurses) answered

the research questions. The samples were selected

through convenience sampling, and the data were

analyzed using the path analysis method and the

Amos 22 software. The following tools were also

used to examine the variables. The data were

analyzed using the structural equation modeling

analysis and the AMOS statistical software. The

tools for collecting information were as follows:

(a) Subjective Well-being Scale, (b) Job Burnout

Questionnaire, (c) Job Performance Questionnaire,

(d) Perceived Social Support Questionnaire,

and (e) a set of demographic questions included

information about the nurses’ gender, education

level, years in nursing profession, typical shift

length, age, and so on.

Subjective well-being scale

Developed by Keyes and Magyar-Moe, this test

was used to measure emotional, psychological,

and social well-being [34]. It had 45 items and

included 13 subscales. The first 12 questions

dealt with emotional well-being, the next 18 ones were on psychological well-being, and the

last 15 questions were about social well-being.

The scale was scored on a Likert scale, with 12

items ranging from always (1) to never (5), and 33

items on a seven-point Likert scale from strongly

disagree (1) to strongly agree (7). The scores

ranged from 45 to 291. The internal validity of

the emotional well-being subscale was 0.91 in

the positive emotion section and 0.78 in the

negative. The psychological and social well-being

subscales had an average internal validity of 0.4

to 0.7, and the total validity of both subscales was

≥ 0.8 [34]. To evaluate the validity of this scale,

factor validity had been used, and the results of

confirmatory factor analysis confirmed the factor

structure of this scale. In his study, Golestanibakht

reported the reliability coefficient and reliability

of the retest to be 0.86 [34]. The reliability of the

subjective well-being scale and the emotional

well-being, psychological well-being, and social

well-being subscales was 0.75, 0.76, 0.64, and

0.76, respectively. The Cronbach’s alpha for the

above-mentioned scale and subscales was 0.80

and 0.64, respectively, indicating the desired

internal consistency of the scale [35].

Job burnout questionnaire

This scale was designed by Maslach and Jackson

and contained 25 questions [36]. The scoring

method was based on a 7-point Likert scale. The

questionnaire had three dimensions, including

emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and

feeling of inefficiency. Questions 1, 2, 3, 6,

8, 13, 14, 16, and 20 dealt with emotional

exhaustion, questions 5, 10, 11, 15, and 22 were

on depersonalization, and questions 4, 7, 12, 17,

18, 19, and 21 were on the feeling of inefficiency.

The frequency and emotional exhaustion severity

scores of >30 and >40, respectively, showed high emotional exhaustion; the frequency and

emotional exhaustion severity scores of 18-29 and

26-39 indicated moderate emotional exhaustion;

and frequency and emotional exhaustion severity

scores of <17 and <25 showed mild emotional

exhaustion. In this study, only the emotional

exhaustion dimension was addressed. In addition,

the test designers calculated the reliability and

validity of the test using the Cronbach’s alpha of

the internal consistency for the frequency of 0.83

and the intensity of 0.84. They also calculated the

total reliability coefficient of the questionnaire for

the frequency of 0.83 and the intensity of 0.53 [37].

The validity and reliability of this questionnaire

in Iran have been determined in many studies by

Iranian researchers and have been confirmed with

scientific validity of >90%. To evaluate the face

and content validity of this tool, Ghaniyoun got the

approval of 10 managements, psychology, nursing,

and emergency medicine lecturers and, using

the Cronbach’s alpha, he obtained the reliability

coefficient of 0.80 for emotional exhaustion, 0.81

for depersonalization, 0.84 for personal adequacy,

and 0.83 for the whole questionnaire [38]. The

results indicated the reliability of the whole

questionnaire and its dimensions.

Job performance questionnaire

This test was designed and standardized by

Patterson to be used to measure employee

performance [39]. The test included 15 articles and

4 dimensions as follows: Observance of discipline,

sense of responsibility at work, cooperation

and teamwork spirit at work, and ability to

continuously improve and correct things. The tool

consisted of 15 questions on a four-point Likert

scale (rarely, sometimes, often, and always) with a

score range of 0 to 3, respectively. The range of the

instrument scores was 0 to 45. The scores 0-11.25

indicated poor performance, 11.25-22.5 showed

moderate performance, 22.5-33.75 indicated good

performance, and 33.75-45 indicated excellent job

performance. The reliability coefficients of this

test had been reported by Arshadi and Piryaaee

using the Cronbach’s alpha and halving methods

as 0.82 and 0.85, respectively [40].

Perceived social support questionnaire

Providing a subjective assessment of social support

adequacy, this scale was designed by Zimet et

al., the questionnaire measured perceptions of

social support adequacy in three sources: Family,

friends, and important people in life [41]. The

questionnaire consisted of 12 questions, each was graded on a seven-point scale from strongly

disagree (1) to strongly agree (7). Based on the

social support sources, each four questions were

attributed to one of the factor groups including

family (items 3, 4, 8, and 11), friends (items 6, 7,

9, and 12), and important people in life (items 1,

2, 5, and 10). It should be noted that in this scale,

an increase in the individual’s scores led to the

increase in their scores of perceived social support

factor. Zimet et al., reported the Cronbach’s alpha

coefficient of 0.81 to 0.98 in nonclinical samples

and confirmed good validity of the scale [42]. In

a preliminary study of psychometric properties

of this scale in samples of Iranian students and

general population (311 students, 431 others),

Besharat et al., obtained the Cronbach’s alpha

coefficients for the whole scale and the items of three

subscales including family, important people, and

friends to be 0.91, 0.87, 0.83, and 0.89, respectively

[43]. In addition, the results of the exploratory and

confirmatory factor analysis confirmed the validity

of the multidimensional scale of perceived social

support by determining three factors (social support,

important people, and friends).

Results

Demographic information

A total of 321 nurses (119 males and 202 females)

participated in this study. The mean age of the

nurses was 31.31 and the standard deviation was

7.96. In terms of education levels, 9% had a lowerthan

bachelor’s degree, 72.9% had a bachelor’s

degree, 16.8% had a master’s degree, and 1.2% had

a PhD. Regarding marital status, 142 nurses were

single, 173 were married, and 6 were divorced. In

addition, 25.2% of the nurses were conscription

law’s conscript, 33% were permanent, 13.7%

were corporate, 14.3% were temporary-topermanent,

4.7% were private contractual, and 8%

were government contractual employees. In terms

of income, 10.3% had incomes below 2 million

tomans, 23.4% had incomes of 2 to 4 million

tomans, 38.9% earned 4 to 6 million tomans, and

27.4% earned over 6 million tomans. Furthermore,

82.6% were working as medical staff but 17.4%

were not medical staff. Finally, 85.7% had rotating

shifts and 14.3% were on duty.

Descriptive indices among research variables

Table 1 shows the mean, standard deviation,

maximum, and minimum scores of the participants

based on the research variables. The results showed that the highest mean score was that of

subjective well-being and the lowest was that of

emotional exhaustion.

Table 1. Descriptive indices among research variables.

| Variable |

Mean (M) |

Standard Deviation (SD) |

Maximum |

Minimum |

| Job performance |

37.07 |

9.81 |

45 |

0 |

| Subjective well-being |

147.77 |

18.98 |

210 |

89 |

| Social support |

45.11 |

8.45 |

60 |

15 |

| Emotional exhaustion |

28.69 |

11.47 |

63 |

9 |

As shown in Table 2, there was a significant positive

relationship between social support and subjective

well-being variables and job performance. On the

other hand, emotional exhaustion had a significant

negative relationship with job performance.

Emotional exhaustion had also a significant

negative relationship with subjective well-being

and social support (P<0.05).

Table 2. Correlation coefficients among research variables.

| Row |

Variable |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| 1 |

Job performance |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| 2 |

subjective well-being |

0.33** |

- |

- |

- |

| 3 |

Social support |

0.25** |

0.47** |

- |

- |

| 4 |

emotional exhaustion |

-0.20** |

-0.43** |

-0.41** |

- |

Note: **P<0.05. |

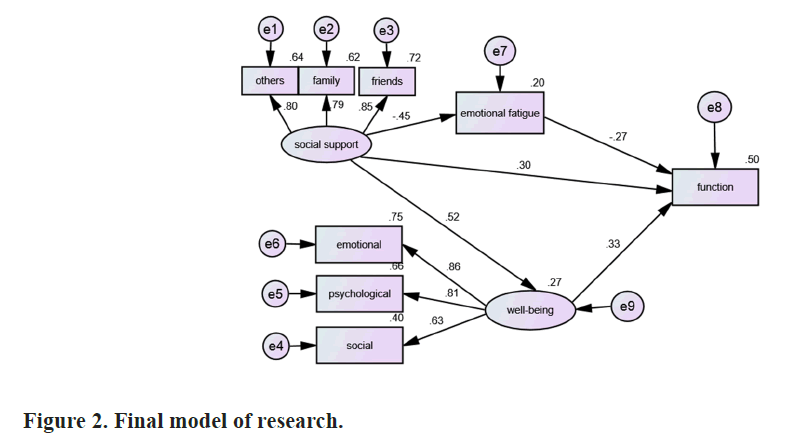

Figure 2 shows the fitted research model. In order

to evaluate the proposed model, the structural

equations method was used in which all the

indicators were in an acceptable range.

According to Table 3, the normalized Chi-Square

(CMIN/DF), Comparative Fit Index (CFI) is 0.945,

Parsimony Normed Fit Index (PCFI) is 0.594,

the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation

(RMSEA) and the HOLTER were obtained

2.25. 0.945, 0.594, 0.067, and 205, respectively,

showing that the model was highly fit.

Table 3. Model fit indicators.

| >Indicator |

>x²/DF |

>RMSEA |

>CFI |

>PCFI |

>HOLTER |

>DF |

| >Job performance |

>2.25 |

>0.067 |

>0.945 |

>0.594 |

>205 |

>17 |

Relationship between social support, job performance

considering Emotional Exhaustion and

subjective well-being in nursing

According to Table 4, social support in a multivariate environment was able to predict

0.304 of the job performance variance. Thus, the

direct effect of social support on job performance

was significant. Furthermore, social support was

able to predict 0.523 of the subjective well-being

variance, and the direct effect of social support on

subjective well-being was significant (P<0.05).

In addition, the standard effect of social support

on emotional exhaustion was -0.447, the direct

effect of which was significant. In other words,

emotional exhaustion decreased with an increase

in social support, (P<0.05). The direct effect of

subjective well-being on job performance with

the standard effect of 0.329 was statistically

significant as well. Moreover, the direct effect

of emotional exhaustion with the standard effect

of -0.227 on job performance was statistically

significant. The Sobel test was used to determine

the significance of the mediating paths of

subjective well-being and emotional exhaustion

and the indirect effect of the independent

variable on the dependent one. The results of

the Sobel test confirmed the mediating roles

of emotional exhaustion (P=0.000, Z=4.358)

and subjective well-being (P=0.000, Z=4.112)

in social support and job performance of the

nurses. Therefore, the indirect effect of social

support on job performance due to emotional

exhaustion and subjective well-being was

statistically significant.

Table 4. Impact analysis: Direct, indirect effects, total score, and standard of the model.

| Emotional exhaustion |

Subjective well-being |

Job performance |

Standard effects |

Path |

| Social support |

Direct |

0.304** |

0.523** |

-0.447** |

| Indirect |

0.294** |

- |

- |

| Total |

0.598** |

0.523** |

-0.447** |

| Subjective well-being |

Direct |

0.329** |

- |

- |

| Indirect |

- |

- |

- |

| Total |

0.329** |

- |

- |

| Emotional exhaustion |

Direct |

-0.273** |

- |

- |

| Indirect |

- |

- |

- |

| Total |

-0.273** |

- |

- |

| Note: **P<0.05. |

Discussion

In this study According to the research findings,

the direct impact of perceived social support was

effective on job performance. The results of the

statistical analysis showed that the overall and

partial fit indices were all at appropriate levels,

and the effect of the perceived social support on job performance was confirmed. In other

words, the more the nurses perceived support

from friends, family, and others, and believed

that their presence and participation was valued

and their well-being and success was taken into

consideration, the greater their job performance

would be. The results of this hypothesis are in line

with the investigations of the relationship between perceived social support and job performance by

Nasurdin et al., AbuAlRub, Kim et al., Wang et al.,

Amarneh et al., [7,16,29,44,45].

To explaining the results, it can be said that people

with high levels of perceived social support are

confident that others will be help them in times of

need, and as a result, they may perceive potentially

stressful events as less stressful. In fact, receiving

multiple types of social support can help a person

directly eliminate or at least reduce negative effects

of potentially stressful situations and make nurses

more competent in their job responsibilities. This

will help improve their performance as well [44].

Thus, perceived social support leads to some kind

of self-confidence and the assurance of an effective

and beneficial response to COVID-19. Hence, job

performance will improve in nurses with high

perceived social support. In general, it should be

stated that as one of the emotion-oriented coping

methods, social support can protect people from

stressful situations by preventing them from

occurring, or help to assess stressful events in

such a way that they get less threatening. It can

also be provided in the form of psychological and

emotional support or information support, tangible

to ultimately increase the employee’s performance

in the organization.

The results showed that perceived social support

had a significant relationship with emotional

exhaustion. In other words, an increase in social

support would lead to decreased emotional

exhaustion. This is consistent with the research of

the studies by Ariapooran, Albar et al., Li et al.,

Ruisoto et al., [12,25-27].

To explain this finding, it can be said that social

support has a protective role against stress, and

since the continuation of stress may cause job

burnout, social support will first reduce stress

with its protective role and ultimately prevents

the occurrence of job burnout. On the other

hand, people with high social support feel more

personal achievements, experience less stress

and anxiety while working, underestimate the

stress of different situations, assess their job more

positively and productively, and evaluate their

abilities to face work challenges more positive

and efficient. These factors first increase their

positive view of the job and job environment and

finally reduce job burnout. In addition, social

support allows individuals to develop positive

social relationships with others and helps balance

emotions and reduce burnout [26]. Thus, nurses

with less supportive resources become vulnerable to emotional exhaustion. Therefore, social support

is a useful and effective factor in improving

nurses’ resilience and stress, especially to deal

with emotional exhaustion.

The results also suggested that social support

could predict the variance of subjective wellbeing,

and the direct effect of perceived social

support on subjective well-being was significant.

This finding is consistent with the results of the

research by Gulacti, Wang et al., Gallagher et al.,

[13,28,33].

It should be stated that high social support

increases positive self-image, self-acceptance,

and feelings of love and worth, while low social

support reduces positive self-image and causes

dissatisfaction in life. Social support also reduces

negative effects of environmental stress and,

consequently, increases the quality of life and life

satisfaction. People with high social support feel

that others care about them, love them, and support

them at the time of difficulties. Such people

have higher self-confidence, self-efficacy, and

optimism, which increase their subjective wellbeing.

Accordingly, Gulacti found in his research

that family support could affect people’s cognitive

patterns of subjective well-being [13]. In other

words, positive relationships and family support

led to positive emotional, social, and cognitive

changes in children, and this was effective in

portraying a more positive and satisfying life.

According to the results, emotional exhaustion

mediated perceived social support and job

performance in nurses. The is in line with the

results of the studies by Taghilou et al., Ariapooran,

Bayrami et al., Ruisoto et al., Halbesleben et al.,

[11,12,17,27,46].

To explain the results, it might be said that job

stressors that lead to emotional exhaustion of

nurses include high workload, long working

hours, lack of support, and inability to leave

work to rest. Job burnout in nurses who spend

long hours at work is manifested in the form of

feeling a lack of personal success in work life.

Therefore, creating strong support systems inside

and outside the workplace and trying to make a

favorable work environment by providing full

support to staff, reducing their workload, and

increasing their freedom of action in decisionmaking

can lead to reduced job burnout [17]. On

the other hand, support from other people makes

individuals more motivated, feel empowered, and

as a result dedicate themselves more to work.

In fact, perceived support of nurses in family,

friends, and colleagues plays an effective role as a

barrier to prevent burnout and stress. Furthermore,

given that low job performance is the result of

emotional exhaustion, this feeling is known as a

mediator of the relationship between perceived

social support and job performance, because a

person who finds more motivation to do his/her

work through the support of those around him/

her becomes so obsessed with his/her work that

she/he will not experience the inefficient feeling

of emotional exhaustion. The nature and severity

of stressors at hospitals have made nurses at high

risk of emotional exhaustion. There is no doubt

that job burnout reduces their efficiency and job

performance, and this will be the starting point

for their lack of motivation in paying attention

to clients and performing their important task

optimally and appropriately. Reduced stress and

workload will lead to reduced job burnout as

well [11]. A study by Ruisoto et al., indicated that

emotional exhaustion, as the main dimension of

job burnout, was the best predictor of general

health in nurses, and social support could improve

negative effects of emotional exhaustion in

medical staff [27].

The findings also confirmed the subjective wellbeing

mediated perceived social support and job

performance in nurses. This is consistent with the

results of the research by Kavoosi et al., Gulacti,

Jia et al., Darvishmotevali et al., Mbatha, who

identified the effects of subjective well-being on

social support [10,13,21,31,32].

It can be acknowledged that social support helps

nurse and healthcare providers withstand workload

stress. Social support has a direct impact on

negative consequences of such stimuli in different

areas of life and reduces the levels of stress

experienced. In fact, exposure to COVID-19 and

systematically introduced quarantine procedures

is more severe in places such as hospitals, health

centers, and diagnostic units, and psychologically,

such a condition has a profound effect on

subjective well-being of the healthcare staff and

thus changes their job performance. Therefore,

nurses’ well-being and life satisfaction improve

through perceiving social support from their

families and managers, and this increases their

performance and empowerment at workplace.

Conclusion

The results of the present study showed a significant positive relationship between

perceived social support and emotional exhaustion

of the nurses during COVID-19. There were

also significant positive relationships between

perceived social support and subjective wellbeing,

between emotional exhaustion and job

performance, and between subjective well-being

and job performance of the nurses. Furthermore,

perceived social support in nurses and attention

to their needs were associated with high scores

of their job performance. On the other hand,

emotional exhaustion was associated with low

scores of perceived social support, and subjective

well-being was associated with high scores of

perceived social supports.

Given that the present study was cross-sectional

and examined the participants over a specific

period of time, conclusion was a bit difficult, and

the cause-and-effect relationships that perceived

social support and the mediating variables of

emotional burnout and subjective well-being had

with job performance could not be found out. In

addition, using a correlational research design

made it more difficult to extract causal results.

Besides, the only data collection tool used in this

study was a questionnaire with a self-report nature

that depended on the nurses’ feelings at the time

of answering the questions. It is suggested that

researchers interested in this field examine other

psychological variables such as shift work, social

capital dimensions, and psychological attributions

in order to better identify the factors affecting

job performance. In this study, a small sample

was extracted from the research population and

most of the subjects were female. However, the

ratio of male and female nurses to their actual

ratio in society was observed in the present

research. Due to the urgency of the conditions,

the researchers collected the data through online

methods that could influence the results. In

addition, the respondents’ psychological stress

could affect their responses. In general, this is

the first study conducted in the Iranian society

to address the concepts of emotional exhaustion

and subjective well-being as the factors affecting

job performance. Future studies are better to try

to replicate these results in larger samples and

use longitudinal and experimental designs to

prove or disprove research hypotheses. They are

also suggested to include the role of depression,

anxiety, and stress in the medical staff dealing with

COVID-19 over a longer period of time in order to

provide appropriate psychological services to help

those under severe stress due to the pandemic.

Other studies such as qualitative ones in this field

are also recommended to reveal more aspects of

this phenomenon.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

IEthical approval was not required for this research

article and any discussion is fully anonymised. All

the participants were informed about the objectives

of the Study and the voluntary nature of their

participation. The questionnaires did not include

names or other ways of personal identification of

the participants to keep the protection of privacy

and maintenance of confidentiality. Informed

consent was obtained from each participant.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during the current study are

available from the corresponding author on

reasonable request.

Competing interests

Not applicable

Funding

Not applicable

Authors’ contributions

SHM, AS, SK, PA conceived and designed the

study, conducted research, provided research

materials, and collected and organized data.

SHM, AS, SK, PA analyzed and interpreted data.

SHM, AS wrote initial and final draft of article,

and provided logistic support. All authors have

critically reviewed and approved the final draft

and are responsible for the content and similarity

index of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the individuals who

participated in the study.

References

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) situation reports. 2020.

- Shahyad S, Mohammadi MT. Psychological impacts of COVID-19 outbreak on mental health status of society individuals: A narrative review. Mil Med. 2020;22(2):184-192.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg N, Weston D, Hall C, Caulfield T, Williamson V, et al. Mental health of staff working in intensive care during COVID-19. Occup Med. 2021;71(2):62-67.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mottaghi S, Poursheikhali H, Shameli L. Empathy, compassion fatigue, guilt and secondary traumatic stress in nurses. Nurs Ethic. 2020;27(2):494-504.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hosseini MA, Sedghi GN, Alamadarloo A, Farzadmehr M, Mousavi A. The relationship between job burnout and job performance of clinical nurses in shiraz shahid rajaei hospital (thruma) in 2016. J Clin Nurs. 2017;6(2):59-68.

[Google Scholar]

- Murphy KR. Is the relationship between cognitive ability and job performance stable over time?. Hum Perform. 1989;2(3):183-200.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Nasurdin AM, Ling TC, Khan SN. Linking social support, work engagement and job performance in nursing. Int J Bus Soc. 2018;19(2).

[Google Scholar]

- Hamdan KB, Al-Ghalabi RR, Al-Zu’bi HA, Barakat S, Alzoubi AA, et al. Antecedents of job performance during covid-19: A pilot study of jordanian public hospitals nurses. J Arch Egyptol. 2020;17(4):339-351.

[Google Scholar]

- Kazmi R, Amjad S, Khan D. Occupational stress and its effect on job performance. A case study of medical house officers of district Abbottabad. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2008;20(3):135-139.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kavoosi Z, Ghaderi AR, Moeenizadeh M. Psychological well-being and job performance of nurses at different wards. Research in clinical Psychology and Counseling. 2014;4(1):175-194.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Taghilou H, Jafarzadeh Gharajag Z. Investigating the relationship between burnout and job performance in the corona epidemic from the perspective of nurses. J Nurs Manag. 2020;9(4):27-33.

- Ariapooran S. Compassion fatigue and burnout in Iranian nurses: The role of perceived social support. Iran J Nurs Res. 2014;19(3):279-284.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gülaçtı F. The effect of perceived social support on subjective well-being. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2010;2(2):3844-3889.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Babaieamiri N. The relationship between job burnout, perceived social support and psychological hardiness with mental health among nurses. AJNMC. 2016;24(2):120-128.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh MD, Stimpfel AW. Nurse reported quality of care: A measure of hospital quality. Res Nurs Health. 2012;35(6):566-575.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- AbuAlRub RF. Job stress, job performance, and social support among hospital nurses. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2004;36(1):73-78.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bayrami M, Movahedi M, Movahedi Y, Azizi A, Mohammadzadigan R. The role of perceived social support in the prediction of burnout among nurses. J Nurs Manag. 2014;3(1):27-34.

[Google Scholar]

- Sarafino EP, Smith TW. Health psychology: Biopsychosocial interactions. John Wiley & Sons. 2014.

[Google Scholar]

- Boren JP. Co-rumination partially mediates the relationship between social support and emotional exhaustion among graduate students. Commun Q. 2013;61(3):253-267.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- del Carmen Pérez-Fuentes M, del Mar Molero-Jurado M, Gázquez-Linares JJ, del Mar Simón-Márquez M. Analysis of burnout predictors in nursing: Risk and protective psychological factors. European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context. 2018;11(1):33-40.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Z, Wen X, Lin X, Lin Y, Li X, et al. Working hours, job burnout, and subjective well-being of hospital administrators: An empirical study based on China’s tertiary public hospitals. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(9):4539.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP, Schaufeli WB, Schwab RL. Maslach Burnout Inventory manual (MBI). 2016.

- Chemali Z, Ezzeddine FL, Gelaye B, Dossett ML, Salameh J, et al. Burnout among healthcare providers in the complex environment of the Middle East: A systematic review. BMC public health. 2019;19:1-21.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khosravi M, Ghiasi Z, Ganjali A. Burnout in hospital medical staff during the COVID-19 pandemic: Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Journal of Natural Remedies. 2021;21(12 (1)):36-44.

[Google Scholar]

- Albar Marín M, García-Ramírez M. Social support and emotional exhaustion among hospital nursing staff. Eur J Psychiatry. 2005;19(2):96-106.

[Google Scholar]

- Li J, Han X, Wang W, Sun G, Cheng Z. How social support influences university students' academic achievement and emotional exhaustion: The mediating role of self-esteem. Learn Individ Differ. 2018;61:120-126.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Ruisoto P, Ramírez MR, García PA, Paladines-Costa B, Vaca SL, Clemente-Suárez VJ. Social support mediates the effect of burnout on health in health care professionals. Front psychol. 2021;11:623587.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang L, Wang H, Shao S, Jia G, Xiang J. Job burnout on subjective well-being among Chinese female doctors: The moderating role of perceived social support. Front psychol. 2020;11:435.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim D, Moon CW, Shin J. Linkages between empowering leadership and subjective well-being and work performance via perceived organizational and co-worker support. Leadersh Organ Dev J. 2018;39(7):844-858.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Napa Scollon C, Lucas RE. The evolving concept of subjective well-being: The multifaceted nature of happiness. Assessing well-being: The collected works of Ed Diener. 2009:67-100.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Darvishmotevali M, Ali F. Job insecurity, subjective well-being and job performance: The moderating role of psychological capital. Int J Hosp Manag. 2020;87:102462.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Mbatha FN. Exploring the relationship between psychological capital, subjective well-being and performance of professional nurses within Uthungulu District Municipality in KwaZulu-Natal. Doctoral dissertation, South Africa. 2016. [ Google Scholar]

- Gallagher EN, Vella-Brodrick DA. Social support and emotional intelligence as predictors of subjective well-being. Pers Individ Differ. 2008;44(7):1551-1561.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes CL, Magyar-Moe JL. The measurement and utility of adult subjective well-being. APA. 2003;pp.411-425. Google Scholar]

- Golestanibakht T, Hashemiyan K, Pourshahriyari M, Banijamali S. Proposed model of subjective well-being and happiness in the population of Tehran. M.A Thesis in Counseling, Alzahra of Tehran

- Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organ Behav. 1981;2(2):99-113. Crossref]

[Google Scholar]

- Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52(1):397-422 Crossref]

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ghaniyoun A, Soloukdar A. Burnout, dimensions and its related factors in the operational staff of Tehran Medical Emergency Center. J Health Promot Manag. 2016;5(3):37-44. [Crossref]

[Google Scholar]

- Paterson TT, Husband TM. Decision-making responsibility: Yardstick for job evaluation. Compens Rev. 1970;2(2):21-31.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Arshadi N, Piryaaee S. The relationship of Islamic work ethics with job satisfaction and intention of personel to leave work. Sceintefic Research Islamic Management. 2014;22(1):213-234.Google Scholar]

- Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52(1):30-41.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Zimet GD, Powell SS, Farley GK, Werkman S, Berkoff KA. Psychometric characteristics of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1990;55(3-4):610-617.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Besharat MA, Keshavarz S, Gholamalilavasani M, Arabi E. Mediating role of perceived social support between early maladaptive schemas and quality of life. J Psychology, 2018; 22(3):256-270. [Crossref]

[Google Scholar]

- Wang ML, Tsai LJ. Work–family conflict and job performance in nurses: The moderating effects of social support. J Nurs Res. 2014;22(3):200-207.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Amarneh BH, Abu Al-Rub RF, Abu Al-Rub NF. Co-workers’ support and job performance among nurses in Jordanian hospitals. J Res Nurs. 2010;15(5):391-401. Crossref]

[Google Scholar]

- Halbesleben JR, Bowler WM. Emotional exhaustion and job performance: The mediating role of motivation. J Appl Psychol. 2007;92(1):93-106.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: Mediating Role of Emotional Exhaustion and Subjective Well-Being in the Relationship between Perceived Social Support

and Job Performance of Nurses during the Corona Pandemic ASEAN Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 25 (5) May, 2024; 1-12.