Introduction

Burnout is a term that seems to describe a

typical occurrence in people’s lives. It has

prompted academics to investigate it further in

order to learn more about what it is and why it

occurs. It has prompted practitioners to consider

new approaches to deal with it, prevent it from

happening, or combat it. As a result, burnout

has always had a favorable reputation. Scholars

and practitioners agree that there is a societal

problem that has to be addressed. Because of their

emotionally exhausting job demands and lengthy

patient interaction, nurses in particular have

reported significant levels of burnout [1]. That

led to investigate the burnout syndrome among nurses in Eradah Complex for Mental Health at

Tabuk-KSA, and to answer, “How is the degree of

burnout among nurses in Eradah complex?”

Literature Review

Burnout syndrome

Herbert Freudenberger, a psychiatrist, and Christina Maslach, a social psychology researcher, started researching burnout 35 years ago. They began publishing about an unknown and unidentified phenomenon that was subsequently described as burnout syndrome in the mid-1970s, independently and in various contexts. Maslach and Jackson created the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) in 1981 as a research tool to assess burnout [2]. Burnout was initially identified as a problem affecting mostly healthcare workers, such as nurses, physicians, and careers, but it quickly spreaded to other professions.

Burnout is a condition characterized by three characteristics: Emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a sense of personal accomplishment [3]. The first of these variables, emotional exhaustion, causes workers to lose their vitality, passion, and confidence. They are emotionally numb; they are disconnected, distant, powerless, and defeated. There is nothing else they can contribute; their mental and emotional reserves are exhausted [4]. Workers who are burned out experience physical issues in addition to mental exhaustion.

Workers who are subjected to the second of these causes, depersonalization, become increasingly pessimistic or cynical about their jobs. They may be impatient and furious; while they once valued cooperation and teamwork, they now attempt to isolate themselves from coworkers, bosses, and service users, “presumably as a means of coping with the work overload” [4].

At the same time, these once high-achievers experience burnout’s third component, diminished personal accomplishment, in the sense that they no longer feel productive or performing properly at work. When examined objectively, this selfassessment at the start of the illness is often not the case. Workers who are on the verge of burnout are frequently perceived by their coworkers to be performing as well as (if not better than) others, at least at first [5].

Prevalence of burnout

Burnout is prevalent in western nations among the general working population, ranging from 13% to 27%, and as high as 70% among physicians globally, with 30%–50% of nurses reaching clinical levels of burnout based on self-report assessments [6].

Burnout syndrome among nurses in KSA

According to a study of international nurses in Saudi Arabia, 45% had high EE (Emotional Exhaustion), 42% had high DP, and 71.5 % had low PA [7]. According to a recent research of primary healthcare nurses in Saudi Arabia, the total incidence of burnout is 89%, with 39%expressing high EE, 38% reporting high DP, and 89 % reporting low PA [8].

Habadi AI, et al. found in their study in terms of socio-demographic data, 90.7% of the nurses were female, 92.3% were non-Saudi, and 68.7% were unhappy with their pay [9]. Furthermore, and unexpectedly, the prevalence of burnout syndrome was 9.34% in this study. However, emotional fatigue alone accounted for 59.89% of the total.

Almubark RA, et al. found in their study the majority of responders 81%. They worked in a pediatric emergency department, and 40% had worked more than 80 hours in the previous two weeks [10]. 70% of the participants said they were afraid of infecting family members at home with COVID-19, and 68% said they were afraid of becoming infected. Overall, 30% of respondents classed as experiencing moderate burnout, according to the survey while only 11% had high levels of burnout.

Alqahtani R, et al. found in their study on burnout syndrome among nurses in a psychiatric hospital in Dammam, Saudi Arabia that the participants’ average age was 35 years [11]. The majority of the study participants were married (69.1%), Saudi (74.7%) men (68.4%), and had worked at the hospital for an average of 13 years. The majority of the individuals (82.3%) reported burnout, which ranged from mild to severe.

For better understanding of burnout syndrome among nurses in Eradah complex using numbers and statistics. This research follows quantitative method using bi-lingo paper-based questionnaire (English/Arabic) build as Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) containing 22 main question plus demographic questions. The questionnaire distributed randomly on employees of nursing sector at Eradah Complex for Mental Health at Tabuk – KSA during the period from October 1, 2021 to December 4, 2021.

Questionnaire

Burnout levels were determined using the maslach burnout inventory-human services survey for medical personnel. The MBI is a 22-item selfreported seven-point Likert scale. 1 represents never, while 7 represents every day. The following are the 22 questions: There are three different scales that can be grouped together: For Emotional Exhaustion (EE), there are nine questions to consider. For Depersonalization (DP), there are five questions, while for Personal Accomplishment (PA), there are eight questions. (Maslach Burnout Inventory Instruments and Scoring Guides) cutoff scores were employed [12].

Sample

The total number of healthcare employees in Eradah complex is 208. Based on random sampling, 135 is a sample size at 95% confidence. The distributed questionnaire is 138, returned 138, 42 is incomplete, and 96 is complete and ready for analysis.

Tool

SPSS version 20 used to do descriptive and inferential data analysis. In descriptive analysis, continuous variables given a mean and Standard Deviation (SD), whereas categorical variables given frequencies and %ages.

Discussion

Participants’ descriptive

Using SPSS to analyze the data: The sample was (n=96). The demographics of the sample as follow: Nationality of participants: The majority of the participants was Saudi citizens (Table 1).

Table 1: Nationality of participants.

| Nationality |

| |

Frequency |

Percent (%) |

| Other (Indian) |

2 |

2.1 |

| Saudi |

94 |

97.9 |

| Total |

96 |

100 |

Gender of participants: Approximately 71% of the participants was male (Table 2). Age of participants: the big age range was from 25 years old to 34 years old (80%) (Table 3).

Table 2: Gender of participants.

| Gender |

| |

Frequency |

Percent (%) |

| Female |

28 |

29.2 |

| Male |

68 |

70.8 |

| Total |

96 |

100 |

Table 3: Age of participants.

| Age |

| |

Frequency |

Percent (%) |

| From 18 years to 24 years |

6 |

6.3 |

| From 25 years to 34 years |

76 |

79.2 |

| From 35 years to 44 years |

14 |

14.6 |

| Total |

96 |

100 |

Marital status of participants: The majority of the participants was married (57%) followed by singles (34%) (Table 4).

Table 4: Marital status of participants.

| Marital status |

| |

Frequency |

Percent (%) |

| Single |

32 |

33.3 |

| Married |

54 |

56.3 |

| Married with Childs |

4 |

4.2 |

| Divorced |

6 |

6.3 |

| Total |

96 |

100 |

Job of participants: The majority of the participants working as nursing specialists (61%) followed by (38%) working as nursing technicians (Table 5).

Table 5:Job of participants.

| Job |

| |

Frequency |

Percent (%) |

| Senior nursing specialist |

2 |

2.1 |

| Nursing specialist |

58 |

60.4 |

| Nursing technician |

36 |

37.5 |

| Total |

96 |

100 |

Working years of participants: The big working range was from 3 years to 10 years (50%) (Table 6).

Table 6: Working years of participants.

| Working years in Eradah |

| |

Frequency |

Percent (%) |

| less than a year |

16 |

16.7 |

| Three to ten years |

48 |

50 |

| One to three years |

18 |

18.8 |

| Ten to twenty years |

14 |

14.6 |

| Total |

96 |

100 |

Working days of participants: All of them working 5 days per week (Table 7).

Table 1: Working days of participants.

| Working days |

| |

Frequency |

Percent (%) |

| 5 days |

96 |

100 |

Working hours of participants: The majority was working 8 hours per day (88%) (Table 8).

Table 8: Working hours of participants.

| Working hours |

| |

Frequency |

Percent (%) |

| 10 hours |

2 |

2.1 |

| 8 hours |

84 |

87.5 |

| 9 hours |

10 |

10.4 |

| Total |

96 |

100 |

Burnout prevalence at Eradah

Using the data of the current sample, the internal reliability of (MBI) using Cronbach’s coefficient alpha, which yielded the estimates of the whole scale as 0.79 (Table 9). The internal consistency of all three subscales (EEd, DP, and PA) was acceptable as 0.82 for Emotional Exhaustion (EE), 0.74 for Depersonalization (DP), and 0.86 for Personal Accomplishment (PA).

Table 9: Reliability statistics.

| Reliability Statistics |

| Dimensions |

Cronbach's alpha |

No. of items |

| Overall |

0.791 |

22 |

| Emotional Exhaustion (EE) |

0.823 |

9 |

| Depersonalization (DP) |

0.741 |

5 |

| Personal Accomplishment (PA) |

0.86 |

8 |

Table 10: Burnout correlations.

| |

EE |

|

DP |

PA |

| EE |

Pearson Correlation |

1 |

.419** |

0.167 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) |

|

0 |

0.103 |

| N |

96 |

96 |

96 |

| DP |

Pearson Correlation |

419** |

1 |

-.305-** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) |

0 |

|

0.003 |

| N |

96 |

96 |

96 |

| PA |

Pearson Correlation |

0.167 |

-.305-** |

1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) |

0.103 |

0.003 |

|

| N |

96 |

96 |

96 |

Note **: Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

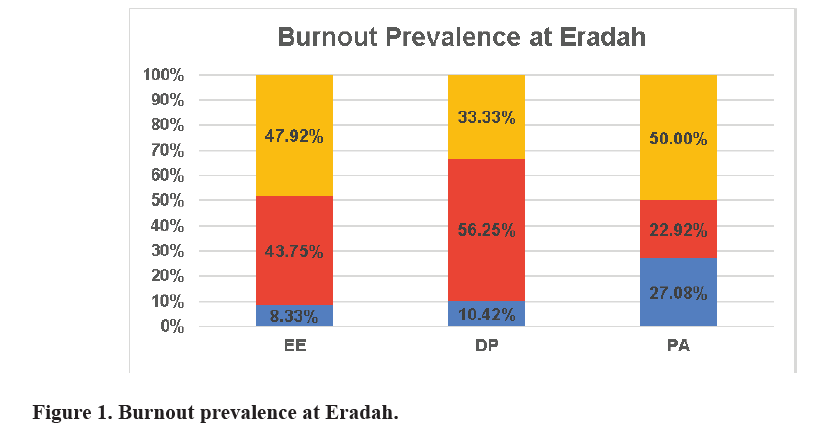

The analysis (Figure 1) shows a moderate high prevalence of burnout syndrome at Eradah Complex (26.19 ± 13.47). As shown in Figure 1, Most of the nurses had a high and moderate degree of Emotional Exhaustion (EE); 46 nurses with a %age of 47.92% and 42 with a %age of 43.75% respectively. Eight nurses who had a low degree of emotional exhaustion with a %age of 8.33%.

Most of the nurses had a moderate degree of depersonalization was 54 with a %age of 56.25% then 32 nurses with a %age of 33.33% had a high degree of Depersonalization (DP); While 10 nurses who had a low degree of Depersonalization with a %age of 10.42%.

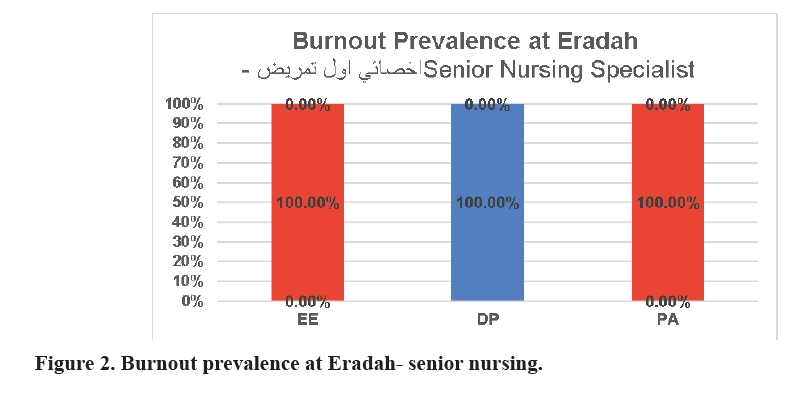

Half of the nurses had a high degree of Personal Accomplishment (PA); 48 nurses with a %age of 50 %. While the number of nurses who had a moderate degree of Personal Accomplishment was 26 with a %age of 27.08% and 8 nurses who had a low degree of personal accomplishment with a %age of 8.33%. When look at burnout prevalence based on respondent’s jobs. For senior nursing specialist (Figure 2), all of them have moderate level of EE and PA with low level of DP.

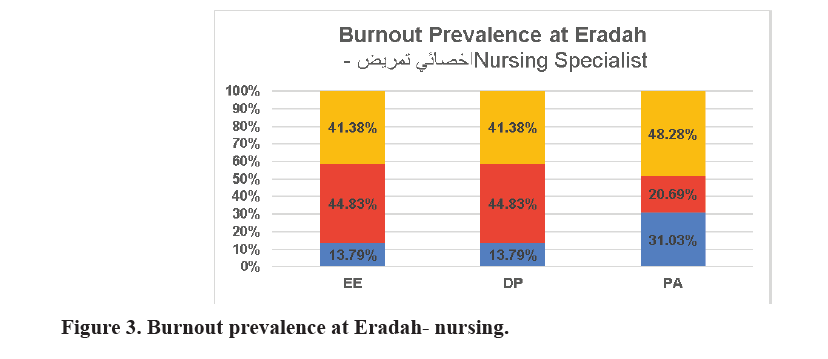

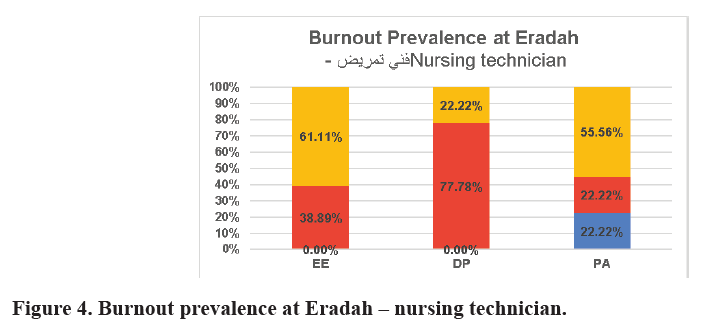

For nursing specialist (Figure 3), most of them have high and moderate level of EE and DP, 41.38% and 44.83% respectively. Almost half of them (48.28%) have high level of PA, third of them (31.03 %) have low level of PA and 20.69% of them have moderate level of PA. For nursing technician (Figure 4), 61.11% of them have high level of EE, 38.89% of them have moderate level of EE. 22.22% of them have high level of DP, 77.78% of them have moderate level of DP. Almost half of them (55.56%) have high level of PA, almost a quarter of them (22.22%) have moderate level of PA and last quarter (22.22%) have low level of PA. As shown in table 10, there is a weak positive correlation between Emotional Exhaustion (EE) and Depersonalization (DP) (0.419) at significance level of 0.01. While there is a weak negative correlation between Personal Accomplishment (PA) and Depersonalization (DP) (-0.305) at significance level of 0.01.

Burnout syndrome has been linked to demographic factors such as gender and age, as well as workrelated stresses (job characteristics and risk exposures) among healthcare employees [13- 17]. As shown at Table 11, there are high level of EE between male more than female that have moderate level. Both male and female have moderate level of DP and PA. All participants with different marital status have high level of EE and moderate level of DP. While single and divorced participants have high level of PA, the married and the married with children have moderate level. Participants with ages ranging from 25 to 44 years old have high level of EE while others from 18 to 24 years old have moderate level. All participants’ ages have moderate level of DP. Participants with ages from 18 to 34 years old have moderate level of PA while participants with ages from 35 to 44 years old have high level of it. Participants with experience from 3 to 20 years work at Eradah complex have high level of EE and same for new workers with less than 1 year. Moderate level of EE was at participants with 1 to 3 working years. While all participants with different working years have a moderate level of DP. Participants with experience from 3 to 20 years work at Eradah complex have high level of PA and Moderate level of PA was at participants with 0 to 3 working years. Participants, working 10 hours per day have high level of EE and DP rather than others working less and low PA.

Table 11:Burnout and socio-demographic characteristics.

| |

|

EE |

|

DP |

|

PA |

|

| |

% of Participants |

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

| Gender |

| Male |

70.83% |

31.79 |

12.31 |

12.44 |

5.34 |

38.32 |

11.02 |

| Female |

29.17% |

23.07 |

6.97 |

9.07 |

3.07 |

36.79 |

8.6 |

| Marital Status |

| Single |

33.33% |

28.38 |

11.94 |

11.75 |

4.26 |

39.31 |

9.23 |

| Married |

56.25% |

28.56 |

11.35 |

11.04 |

5.32 |

37.04 |

10.94 |

| Married with childs |

4.17% |

27.5 |

0.58 |

9.5 |

0.58 |

35.5 |

6.35 |

| Divorced |

6.25% |

41.33 |

12.53 |

15 |

6.75 |

39.33 |

13.69 |

| Age |

| 18-24 |

6.25% |

19.33 |

3.39 |

11.33 |

2.25 |

37 |

1.55 |

| 25-34 |

79.17% |

29.45 |

11.13 |

11.5 |

5.56 |

36.53 |

10.91 |

| 35-44 |

14.58% |

32.43 |

14.92 |

11.29 |

1.98 |

45.57 |

4.5 |

| Years worked at Eradah |

| less than a year |

16.67% |

29.88 |

12.64 |

12.38 |

5.32 |

33.13 |

5.94 |

| One to three years |

18.75% |

25.67 |

13.55 |

12.44 |

7.91 |

36.44 |

12.03 |

| Three to ten years |

50.00% |

30.67 |

10.72 |

11.21 |

4.07 |

39.42 |

11.13 |

| Ten to twenty years |

14.58% |

28.29 |

11.45 |

10 |

2.15 |

39.86 |

7.81 |

| Work hours / day |

| 8 hours |

87.50% |

29.57 |

11.69 |

11.4 |

5.22 |

38.02 |

10.38 |

| 9 hours |

10.42% |

22.2 |

4.18 |

11.2 |

3.29 |

38.2 |

11.1 |

| 10 hours |

2.08% |

51 |

0 |

15 |

0 |

30 |

0 |

Conclusion

Nurses play an important part in today’s healthcare system. This research will assist to investigate more about the causes of the burnout in future researches because of the moderate high degree of overall burnout prevalence at Eradah Complex (26.19 ± 13.47). Burnout prevailed more between nursing technicians (27.40%) than nursing specialists (25.67%) and senior nursing specialists (19.33%). The high level of Emotional Exhaustion (EE) between nurses-especially nursing specialists and technicians who are experienced more than 3 years and working more than 8 hours per day - needs from the management of Eradah complex for mental health at Tabuk – KSA to keep support this kind of researches to investigate more and develop policies to enhance nurses working environment and improve quality of health care system.

Limitations

There are some limitations for this research due

to constant response for most of the participants

about working days and hours so it was impossible

to make a correlation test on those variables and

burnout syndrome to understand more about

the causes of it. This opened the door for the

future research to expand this research among

many mental hospitals in KSA to investigate

more variables that could affect burnout and to

investigate more about more causes of burnout at

Eradah complex and to introduce solutions for it.

Ethical Considerations

Participants ensured that the data collected would

be kept confidential. Participants have the option

to leave the research at any time. Prior to data collection, the researcher obtained institutional

approval from research accreditation committee

in Tabuk in September 2021.

References

- Demerouti E, Bakker A B, Nachreiner F, Schaufeli WB. A model of burnout and life satisfaction amongst nurses. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32(2):454-464.

[Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Maslach C, Leiter MP, Jackson SE. Making a significant difference with burnout interventions: Researcher and practitioner collaboration. J Organ Behav.2012;33(2):296-300.

[Crossref][Google Scholar]

- Maslach C. Understanding burnout: Definitional issues in analyzing a complex phenomenon. Job, stress and burnout. 1982;29-40.

- Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52(1):397-422.

[Crossref][Google Scholar]

- Ericson-lidman E, Strandberg G. Burnout: Co-workers’ perceptions of signs preceding workmate’s burnout. J Adv Nurs. 2007;60(2):199–208.

[Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Wilkinson H, Whittington R, Perry L, Eames C. Examining the relationship between burnout and empathy in healthcare professionals: A systematic review. Burnout Research. 2017;6:18–29.

[Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Al-Turki HA, Al-Turki R, Al-Dardas H, Al-Gazal M, Al-Maghrabi G, et al. Burnout syndrome among multinational nurses working in Saudi Arabia. Ann Afr Med. 2010;9(4):226-229.

[Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Shahin M, Al-Dubai S, Abdoh D, Alahmadi A, Ali A, et al. Burnout among nurses working in the primary health care centers in Saudi Arabia, a multicenter study. AIMS Public Health. 2020;7(4): 844-853.

[Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Habadi AI, Alfaer SS, Shilli RH, Habadi MI, Suliman SM, et al. The prevalence of burnout syndrome among nursing staff working at king Abdulaziz University hospital, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, 2017. Divers Equality Health Care, 2018;15(3):122.

[Google Scholar]

- Almubark RA, Almaleh Y, BinDhim NF, Almedaini M, Almutairi AF, et al. Monitoring burnout in the intensive care unit and emergency department during the COVID-19 pandemic: The Saudi Arabian experience. Middle East J Sci Res. 2009;14(2):12-21.

[Crossref][Google Scholar]

- Alqahtani R, Al-Otaibi S, Zafar M. Burnout syndrome among nurses in a psychiatric hospital in Dammam, Saudi Arabia. Nurs Midwifery Stud. 2020;9(2):110-115.

[Crossref][Google Scholar]

- Mind Garden, Inc (2021). MBI-Human Services Survey.

- Seidler A, Thinschmidt M, Deckert S, Then F, Hegewald J, et al. The role of psychosocial working conditions on burnout and its core component emotional exhaustion: A systematic review. JOMT. 2014;9(10):1-13.

[Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Adriaenssens D, De Gucht D, Maes S. Determinants and prevalence of burnout in emergency nurses: A systematic review of 25 years of research. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52(2):649–661.

[Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Gonnelli C, Raffagnino R. Work–family conflict in nursing: An integrative review of its antecedents and outcomes. JPBS. 2017;3(1):61–84.

[Crossref][Google Scholar]

- Raffenaud A, Unruh L, Fottler M, Liu AX, Andrews D. A comparative analysis of work–family conflict among staff, managerial, and executive nurses. Nurs Outlook. 2020;68(2):231-241.

[Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Alsayed R, Al-Dubai S, Ibrahim H. Burnout and associated factors among nurses working in a mental health hospital, Madinah, Saudi Arabia. EJCM. 2021;39(3):10-20.

[Google Scholar]