Introduction

COVID pandemic required many integrated strategies to prevent contagion, so that mortality could be reduced and the impact on people’s lives could be minimized [1,2]. The greatest concern was to contain viral contamination, and the actions taken to prevent the spread of the virus provided an increase in cases of anxiety, depression, and stress associated with fear and uncertainties [3]. Also, in relation to the pandemic, the effects on the mental health of the population are greater than the number of deaths [4,5]. Systematic review studies, with population samples from several countries, showed impacts on mental health with a high prevalence of anxiety (31.9%), depression (33.7%), and stress (29.6%), in addition to other changes on the psychological well-being of specific populations and the general population [6-8].

The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) reported that more than four in 10 Brazilians had anxiety problems as a result of the pandemic [9]. According to Brazilian research on mental health during the pandemic, 40.4% of the population often felt sad or depressed, 52.6% often felt anxious or nervous; 43.5% reported the onset of sleep disorders and 48.0% reported having worsened pre-existing sleep disorders. These symptoms were more present among young adults, women, and people with a history of depression [10]. Women who suffer from anxiety and depression who are mothers or caretakers are more likely to contribute to an insecure attachment in their child [11].

Moreover, in addition to having impacted people's lives, the pandemic affected their work, generating unemployment in several segments, which made inequality evident, as the black and brown people, and low-income households were the most affected groups [12]. Another result of this pandemic included the increase in solid waste disposal, which is associated with the greater search for single-use materials [13]. The waste workers were directly affected. The biggest issue is the incorrect disposal of these objects, as materials such as masks are constantly discarded in inappropriate places and few people care about those who work in urban cleaning and are dealing directly with the potentially contaminated waste [14]. A study conducted to identify the impact of improper disposal of disposable face masks concluded that they are a pollutant. In addition to affecting the environment, they are also harmful to human health [15].

It is estimated that, worldwide, some fifteen million individuals work informally as waste pickers, by picking and recovering recyclable material, of whom 4 million in Latin America [16]. These people are the first to suffer the consequences of the inadequate management of solid wastes. The waste pickers are workers who sort recyclable materials to sell. In Brasilia there are approximately 1300 waste pickers [17]. Most of them worked in Estrutural waste open dump considered the largest open dump in the Latina America and second largest in the world. It was closed in 2018 and the waste pickers were relocated to Waste Recovery Facilities where they are still working [18].

Regarding the work of waste pickers, several groups mentioned having mental health problems. According to Tereza, from Cooper Viva Bem in São Paulo, “the pandemic affected us both financially and psychologically, because we stayed at home, everyone was afraid, and everyone was not being paid” [19]. When it comes to waste pickers, this reality is alarming, if we consider that women are 40% more likely than men to suffer from a mental health disorder [20]. Another group of waste workers are the street sweepers. In 2022 there were a total of 2404 who worked in Brasilia, Brazil [17]. They are responsible for cleaning the city. Many of them work in trucks collecting waste from houses, commerces, public and private departments, malls, and others work sweeping the streets. The working conditions from these two groups of waste workers are very different since the waste pickers work in indoor facilities, do not have a salary, neither health insurance, and other working rights, such as, getting retired [21]. But, waste workers in general are exposed to many occupational risks ergonomic, biological, chemical, physical, social and others [22].

The work-illness relationship is considered multifactorial, so that some individuals more vulnerable to these manifestations may have the occupation as one factor that contributes to emotional exhaustion and can be aggravated by the context of the pandemic. Therefore, the concept of mental health is related both to the criteria in the psychiatry charts and to social contexts, since an environment that respects and protects basic civil, political, socioeconomic, and cultural rights is fundamental for the promotion of mental health [23]. In view of the above, this study aims to analyse the factors associated with the adverse mental health of waste pickers and street sweepers in Brasília, Brazil, during the COVID-19 pandemic. Since these groups of professionals should be considered essential work, they were totally exposed to be contaminated by the SARCOV-2 virus and should continue work during the pandemic.

In Brasilia, Brazil most of the waste pickers are women, so they are double vulnerable, by job and by their social condition. The expectations of this study is to highlight the mental conditions of these workers to show police makers do protect them since they are almost invisible to society.

Materials and Methods

This was an observational, cross-sectional cohort study, with a quantitative approach, which used data from the thematic project entitled “The impacts of COVID-19 on the life and work of waste pickers in Brasilia”, carried out in 2020 and 2021.

In this study, the eligible workers were: a) “waste pickers” who work in the Integrated Recycling Complex (CIR), Waste Screening Centre (CTRs) and in the Waste Recovery Facilities (IRRs); b) street sweepers, workers involved with sweeping, collecting, inspecting, monitoring, mobilizing, drivers of waste collection trucks and Occupational Safety technicians who work in the urban cleaning in Brasília and are directly linked to waste management. According to the Urban Cleaning Service (SLU), approximately 1,200 pickers of recyclable materials were registered in cooperatives hired by the government of Brasília, and 2,404 were responsible for urban cleaning hired from private companies.

Initially, the heads and managers of the cooperatives of the collaborating cleaning companies in Brasília answered an online questionnaire developed by the researchers and prepared on Google Forms. Data related to COVID-19 cases were collected to know if the workers who had COVID showed more mental illness, in addition to the workers’ phone numbers and information on the hygiene and safety measures adopted.

Based on the definition of the target population for the study and access to the workers contact, all individuals were considered eligible and invited to participate in the study. Despite the eligibility of all workers, considering the pandemic context, we chose a consecutive non-probability sampling that would guarantee a minimum number of participants in the study. Thus, we considered a prevalence of occurrence of the outcome of 50%, a sampling error of 5%, and a confidence level of 95%. The minimum sample size was 292 waste pickers and 332 street sweepers. The calculation was performed at: https://www.openepi.com/Sam pleSize/SSPropor.html.

For data collection, a semi-structured questionnaire containing 80 questions and organized in Google Forms, developed by the researchers, was used. The form was entitled “Monitoring COVID-19 cases among street sweepers and waste pickers of recyclable materials in Brasília”. The instrument was divided into 3 blocks that included Sociodemographic Data; Suspected and Confirmed Cases of COVID-19 and the Self Report Questionnaire (SRQ 20, validated in Brazil [24]. The SRQ-20 is a self-administered instrument, which means that individuals can answer the questions by making self-assessment. When convenient, it can be applied by an interviewer. The SRQ-20 test contains 20 questions with yes/no answers about depressive-anxious mood, somatic symptoms, decreased vital energy, and depressive thoughts. This method is used to evaluate the health and adverse mental health of individuals. It has been used for research with different groups of workers, and when the result is ≥ 7, adverse mental health should be considered [25].

Waste pickers and street sweepers received a call to answer the questionnaire. Their contact was sent to us by the Urban Cleaner Service. Before the beginning of the interview, the participants were provided with all the guidelines on the purpose of the research, and all doubts were cleared. The participants could answer the questions by phone or through the link provided by the research team.

The dependent variable of the study was adverse mental health defined by the SRQ-20 result greater than or equal to 7. The independent variables were: sex (female, male); age group (18–39 years old, 40 years and older); marital status (married/common-law relationship, single/divorced);race/skin color (white, black, brown); labour activity (street sweeper, waste Picker); COVID-19 (laboratory diagnosis) (no, yes); health problems (grouped from a list of health problems (Cardiovascular, respiratory, mental health, gastrointestinal, renal or reproductive, metabolic, muscle injury, other problems); number of health problems (classified based on the sum of reported problems) (none, 1, 2, 3 or more). A descriptive analysis was performed using absolute and relative frequency, and the Chi-square association test was calculated, considering the outcome of interest. The magnitudes of the associations were estimated using the Prevalence Ratios (PRs) in the Poisson regression model. A category of each variable was used as a reference. Initially, a bivariate analysis was performed. Then, the variables that were associated with significance level p ≤ 0.20 were selected for the multiple model. The level of significance in the analysis was 5%. Data analyses were performed using the Stata software version 16.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, United States.

Results

Considering the total study sample of 886 workers, 71 workers (8.0%) presented adverse mental health according to the SRQ-20 instrument. Of these, the majority were female 56 (12.9%). Regarding age, the most prevalent age group was 18-39 years old, with 46 (10.1%) workers. Black and brown people presented a higher incidence of adverse mental health, as well as those who were married or had common-law partners. As for labor activity, waste pickers had a higher prevalence of adverse mental health in relation to street sweepers (Table 1).

| 2020 and 2021 |

Yes |

No |

Total |

P-value |

| n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

|

| Sex |

| Male |

15 |

3.3 |

437 |

96.7 |

452 |

51 |

<0.00 |

| Female |

56 |

13 |

378 |

87.1 |

434 |

49 |

- |

| Age group |

| 18–39 years old |

46 |

10 |

407 |

89.9 |

453 |

52 |

0.024 |

| 40 years and over |

25 |

6 |

394 |

94 |

419 |

48 |

- |

| Marital status |

| Married/common-law |

49 |

9 |

492 |

91 |

541 |

61 |

0.152 |

| relationship |

| Single/divorced |

22 |

6.4 |

323 |

93.6 |

345 |

39 |

- |

| Race/Skin color |

| White |

8 |

6.4 |

116 |

93.6 |

124 |

14.1 |

0.009 |

| Black |

24 |

14 |

150 |

86.2 |

174 |

19.9 |

- |

| Brown |

39 |

6.8 |

539 |

93.2 |

578 |

66 |

- |

| Labor activity |

| Street sweeper |

33 |

5.5 |

568 |

94.5 |

601 |

67.9 |

0 |

| Waste picker |

38 |

13 |

247 |

86.7 |

285 |

32.1 |

- |

| COVID-19 |

| No |

52 |

7.2 |

670 |

92.8 |

722 |

81.5 |

0.062 |

| Yes |

19 |

12 |

145 |

88.4 |

164 |

18.5 |

- |

| No. of health problems |

| 0 |

27 |

4.7 |

545 |

95.3 |

572 |

64.6 |

<0.00 |

| 1 |

16 |

9 |

162 |

91 |

178 |

20 |

- |

| 2 |

15 |

18 |

70 |

82.3 |

85 |

9.6 |

- |

| 3 or more |

13 |

25 |

38 |

74.6 |

51 |

5.8 |

- |

Table 1: Prevalence of Adverse Mental Health (SRQ-20), According to the Workers' Characteristics, Brasilia, 2020 and 2021.

Regarding the associated factors, it was observed that women (PR: 3.36; 95% CI:1.86;6.08), workers between 18–39 years old (PR: 2.19; 95% CI: 1.32;3.65), waste pickers (PR: 1.65; 95% CI:1.01;2.70), workers who reported two (PR: 3.24; 95% CI:1.72; 6.12) or three or more (PR:4.73; 95% CI:2.40;9.32) health problems had the highest prevalence of adverse mental health (Table 2).

| 2020 and 2021 |

PR (95% CI) |

P-value |

RPa (95% CI) |

P-value |

| Sex |

| Female |

3.89 (2.20;6.87) |

<0.001 |

3.36 (1.86;6.08) |

<0.001 |

| Male |

Reference |

- |

Reference |

- |

| Age group |

| 18–39 years old |

1.70 (1.05;2.77) |

0.032 |

2.19 (1.32;3.65) |

0.003 |

| 40 years and over |

Reference |

- |

Reference |

- |

| Marital status |

| Married/Common law |

Reference |

- |

- |

- |

| relationship |

| Single/divorced |

0.70 (0.43;1.16) |

0.172 |

- |

- |

| Race/Skin color |

| White |

Reference |

- |

- |

- |

| Black |

2.14 (0.96;4.76) |

0.063 |

- |

- |

| Brown |

1.95 (0.49;2.24) |

0.908 |

- |

- |

| Labor activity |

| Street sweeper |

Reference |

- |

Reference |

- |

| Waste picker |

2.43 (1.52;3.87) |

<0.001 |

1.65 (1.01;2.70) |

0.048 |

| COVID-19 |

| No |

Reference |

- |

Reference |

- |

| Yes |

1.61 (0.95;2.72) |

0.076 |

1.87 (1.09;3.19) |

0.022 |

| No. of health problems |

| 0 |

Reference |

- |

Reference |

- |

| 1 |

1.90 (1.03;3.53) |

0.041 |

1.83 (0.98;3.43) |

0.058 |

| 2 |

3.74 (1.99;7.03) |

<0.001 |

3.24 (1.72; 6.12) |

<0.001 |

| 3 or more |

5.40 (2.79;10.47) |

<0.001 |

4.73 (2.40;9.32) |

<0.001 |

Table 2: Prevalence ratio and adjusted prevalence ratio with the respective values of the 95% confidence interval of adverse mental health (SRQ-20), according to the characteristics of the workers, Brasilia, 2020 and 2021.

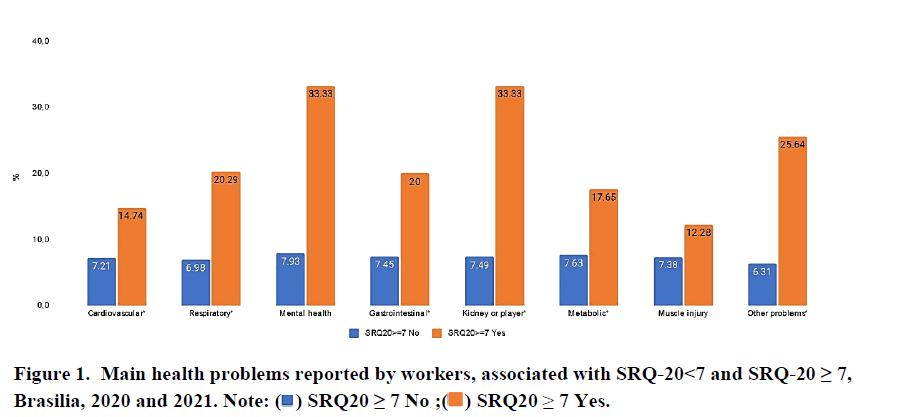

Workers who presented SRQ-20 ≥ 7 showed a higher number of health problems. It is noteworthy that workers who reported mental or renal or reproductive health problems presented almost four times more adverse mental health (Figure 1).

As for the SRQ-20 responses, the workers showed depressive-anxious mood, in total, 167 (18.8%) felt nervous, tense or worried, 99 (11.2%) were easily frightened, 141 (16.0%) felt sad lately and 77 (8.7%) had been crying more than usual. Regarding somatic symptoms, 111 (12.5%) workers reported having had frequent headaches. In the responses related to the decrease in vital energy, 60 (6.8%) got tired easily and 69 (7.8%) felt tired all the time (Table 3).

| 2020 and 2021 |

Waste picker |

Street sweeper |

P-Value |

| Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

| n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

| Depressive-anxious mood |

| Do you feel nervous, tense, or worried? |

70 |

24.6 |

215 |

75.4 |

97 |

16.1 |

504 |

83.9 |

0.003 |

| Do you feel scared easily? |

43 |

15.1 |

242 |

84.9 |

56 |

9.3 |

545 |

90.7 |

0.011 |

| Have you felt sad lately? |

58 |

20.3 |

227 |

79,7 |

83 |

13.8 |

518 |

86.2 |

0.013 |

| Have you been crying more than usual? |

33 |

11.6 |

252 |

88.4 |

44 |

7.3 |

557 |

92.7 |

0.036 |

| Somatic symptoms |

| Do you frequently have headaches? |

62 |

21.8 |

223 |

78.2 |

49 |

8.2 |

552 |

91.8 |

<0.00 |

| Do you sleep badly? |

45 |

15.8 |

240 |

84.2 |

83 |

13.8 |

518 |

86.2 |

0.434 |

| Do you have unpleasant sensations in your stomach? |

20 |

7 |

265 |

93 |

54 |

9 |

547 |

91 |

0.323 |

| Do you have poor digestion? |

19 |

6.7 |

266 |

93.3 |

33 |

5.5 |

568 |

94.5 |

0.487 |

| Do you have lack of appetite? |

18 |

6.3 |

267 |

93.7 |

23 |

3.8 |

578 |

96.2 |

0.1 |

| Do you have shaky hands? |

13 |

4.6 |

272 |

95.4 |

26 |

4.3 |

575 |

95.7 |

0.873 |

| Decrease in vital energy |

| Do you get tired easily? |

30 |

10.5 |

255 |

89.5 |

30 |

5 |

571 |

95 |

0.002 |

| Do you have difficulty in making decisions? |

39 |

13.7 |

246 |

86.3 |

58 |

9.7 |

543 |

90.3 |

0.072 |

| Do you find it difficult to perform the daily activities with satisfaction? |

24 |

8.4 |

261 |

91.6 |

32 |

5.3 |

569 |

94.7 |

0.077 |

| Do you have difficulties at work? |

10 |

3.5 |

275 |

96.5 |

11 |

1.8 |

590 |

98.2 |

0.125 |

| Do you feel tired all the time? |

33 |

11.6 |

252 |

88.4 |

36 |

6 |

565 |

94 |

0.004 |

| Do you have difficulty in thinking clearly? |

31 |

10.9 |

254 |

89.1 |

55 |

9.2 |

546 |

90.8 |

0.418 |

| Depressive thoughts |

| Do you feel unable to play a useful role in your life? |

21 |

7.4 |

264 |

92.6 |

32 |

5.3 |

569 |

94.7 |

0.231 |

| Have you lost interest in things? |

24 |

8.4 |

261 |

91.6 |

35 |

5.8 |

566 |

94.2 |

0.147 |

| Do you feel less active and alert? |

39 |

13.7 |

246 |

86.3 |

35 |

5.8 |

566 |

94.2 |

<0.00 |

| Do you feel less optimistic about the future? |

55 |

19.3 |

230 |

80.7 |

62 |

10.3 |

539 |

89.7 |

<0.00 |

Table 3. SRQ-20 Response Profile = 7, according to labor activity, Brasilia, 2020 and 2021.

Discussion

This study analysed the mental health impacts of waste pickers and street sweepers from Brasilia, Brazil, during the COVID-19 pandemic. These workers are responsible for the selective collection and cleaning maintenance of public spaces, being more vulnerable and exposed to COVID-19 due to working conditions and mainly because that they have direct contact with materials that are discarded by the population with risks of contamination by the virus. This impasse led the suspension or reduction of selective collection activities in some cities in Brazil, including Brasilia [26]. The waste workers, especially the waste pickers are a vulnerable population, segmented from the society and during this time, they were even more disadvantaged which finally tipped the scale and affected mental health in women. As a result, this study found that women suffered from anxiety and depression and this can have an impact on their children. Women who suffer from anxiety and depression who are mothers or caretakers are more likely to contribute to an insecure attachment in their child [27]. This can have long term adverse developmental effects in their child lives and contribute to outcomes such as anxiety, depression, low self-esteem, poor self-regulation. During the pandemic, concerns, fear, and insecurity affected all human beings. Specific groups of workers were greatly affected, such as health professionals. However, workers who are often invisible to society, such as street sweepers and waste pickers, were also exposed. In this study, it was observed that 8.0% of workers had SRQ-20 ≥ 7, which is equivalent to adverse mental health. Women were 3 times more likely to have adverse mental health than men, and the more chronic health problems associated with it, the greater the adverse mental health. In Bahia, Brazil, some cooperatives reduced the working hours and allowed the elderly people to stay at home, and they continued to receive financial support as a measure to avoid contamination by the virus [28]. In Brasília, on March 21, 2020, the government suspended the garbage selective collection to minimize cases of the disease among waste pickers and decreed the closure of recycling warehouses due to the high risk of contagion and spread of the virus, leaving waste pickers without the main source of income. However, only these workers from Brasília were affected by this measure. As street sweepers are considered essential services workers, they continued to work during this period, being more exposed to the virus [29]. Moreover, the increase in determinants that affect the mental health of the entire population, such as high unemployment rate, insecurity, and decreasing wages, negatively influence the health of the community, especially those who are already disfavoured [30]. It is usually not easy to recognize the determinants of the process of distress and mental illness, and it becomes even more difficult when people are aware that if they get sick, they will not have a source of income, which happens to waste pickers, who receive by production. Worse than that is what happens with the income of sugarcane workers, since they are motivated to compete to reach the goal of sugarcane cutting, causing their illness and even the premature death of these workers [31]. The sample profile of this study showed a predominant age range of 18-39 years old. The majority declared themselves brown and black in the two groups of workers (Table 1). Studies corroborate this finding, showing that predominantly the waste pickers self-declare as black or brown. This reinforces that the labor market is the channel through which the structure of inequalities present in the social dynamics is very strongly revealed [32]. Brazil has admittedly high levels of socioeconomic inequality (in) directly linked to racism [33-35]. This structural element of society has its effects sharpened in times of uncertainty, with a tendency to produce results proportionally unfavourable to groups already vulnerable [36]. Women are more likely to develop mental health disorders, which suggests a negative impact of the pandemic on the lives of these workers. It is likely that gender relations, family structure, and the losses of job conformation interfere with family structure, that is, the strenuous journey of women in the fulfilment of family care, reproduction, and support of homes impact mental health in several ways [37,38]. In this study, 56 (12.9%) of the women reported possible mental distress with SRQ-20 ≥ 7. A study conducted to outline the psychological well-being profile of urban cleaning workers in Campina Grande–PB showed that women have the most anxious profile. They also feel more tense, negative, and have more difficulty in performing activities, compared to men [39]. Due to quarantine and social isolation, cases of domestic violence have increased [40]. A study conducted in Brasília showed the interface between domestic violence and psychological distress, from the perspective of women waste pickers, reflecting how these women have become more vulnerable to psychological distress, as they were away from a possible support network [41]. Mental stress has the potential to cause the development of other diseases and vice versa. Research shows evidence that it can cause the emergence of cardiovascular diseases, corroborating the findings of this study in which workers who presented mental distress manifested a higher prevalence of other health problems, 7.21% of which cardiovascular diseases (Figure-1). The pandemic provoked and/or aggravated symptoms of depression and anxiety in people, especially among the so-called essential workers, during the peak of the pandemic [42,43]. In an analysis carried out to identify problems of sadness/depression, nervousness/anxiety in the Brazilian population during the COVID-19 pandemic, it was revealed that, during the period of pandemic and social distancing, 40% of Brazilians felt sad or depressed and 52% said they were feeling anxious or nervous [44]. In this study, 17.05% of the respondents revealed that they felt sad, 18.25% reported that they felt nervous, tense, and worried. The lower prevalence of mental problems in these workers may be due to their life history, trajectory of struggles and resilience to survive in a dignified and honest manner.

Conclusion

In the study, it was observed that men were more contaminated by COVID-19. Despite of this, women are more likely to develop adverse mental health in both groups of workers. Since they are young adults and responsible to care of their children, this condition can impacts child´s lives. Another situation is that women who suffer mental illness cannot work and produce a lot, so their income will be reduced. The work performed by waste pickers and street sweepers is extremely important for the environment and health of communities, requiring public policies thatthe physical and mental health of these professionals, in addition to ensuring all necessary safety to avoid contamination and other occupational risks that may be caused by the routines of these professions.

Due to the characteristics of the professions, waste pickers and street sweepers are workers who have the ability to deal with problems and overcome their difficulties, which may have contributed to the low impact that COVID-19 had on the mental health of these workers. Still, it is necessary to think about actions to strengthen environmental education to sensitize the population and the recognition of the importance of the correct disposal to facilitate the work of these essential professionals. It is understood that the search for mental health support is necessary and should be encouraged within the organizations of waste pickers and companies where the street sweepers work, to monitor cases and establish early interventions and maintain the mental integrity of these workers, so that adverse mental health does not affect productivity at work and especially the quality of life of these professionals. Searching for partnerships with universities is a viable solution, considering that there are extension projects and mental health academic leagues that can help minimize the damage to the mental health of these workers.

Limitations

This study was conducted according to a non-probabilistic sampling. Despite the limitation of the type of sampling, the findings are important for this population since these workers are considered an invisible population.

Author Contributions

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Brasilia-Faculty of Ceilandia under the number 40925120.1.0000.8093.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ferrer R. COVID-19 pandemic: The greatest challenge in the history of Intensive care. Medicina Intensiva. 2020; 44(6): 323-324.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- COVID-19 pandemic: The greatest challenge in the history of Intensive care

- Miranda TS, Soares GFG, Araujo BE, Fagundes GHA, Amaral HLP, et al. Incidence of cases of mental disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic. Electronic Journal Scientific Collection. 2020; 17(5): 353-361.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Faro A, Bahiano MA, Nakano TC, Reis C, Silva BFP. COVID-19 and mental health: The care emergency. Psychology Studies (Campinas). 2020; 37(10): 10-20.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Ornell F, Schuch JB, Sordi AO, Kessler FHP. Pandemic of fear and COVID-19: Impact on mental health and possible strategies. Corona Virus-COVID-19. 2020; 10(2): 23-28.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Salari N, Far AH , Jalali R, Raygani AV, Rasoulpoor S, et al. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Globalization and Health. 2020; 16(1): 50-57.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shevlin M, McBride O, Murphy J, Miller J G, Hartman T K, et al. Anxiety, depression, traumatic stress and COVID-19-related anxiety in the uk general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. Bitish Journal of Psychology Open. 2020; 6(6): 120-125.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Luo M, Guo L, Yu M, Jiang W, Wang H. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research. 2020; 291(9): 59-65.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- OPAS. PAHO highlights underrecognized mental health crisis caused by COVID-19 in the americas. 2021, Washington, DC.

- Barros MBA, Lima MG, Malta CD, Szwarcwald CL, Azevedo RCS, et al. Report of sadness/depression, nervousness/anxiety and sleep problems in the brazilian adult population during the COVID-19 pandemic. Epidemiology and Health Services. 2020; 29(4): 63.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Coles DC, Cage J. Mothers and their children: An exploration of the relationship between maternal mental health and child well-being. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2022; 26(2):1015-1021.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bridi MA. The COVID-19 pandemic: crisis and deterioration of the Labor Market in Brazil. Advanced Studies. 2020; 34(100): 141-165.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Vaccination of urban cleaning service sweepers begins. Brasilia Agency. 2021

- Bispo D. Waste pickers: the invisible frontline. Le Monde Diplomatique Brasil.2020.

- Silva WLDA. The importance of garis in pandemic times. 2020 the year of the coronavirus pandemic. 2020.

- Pisano V. The brazilian national solid waste policy: perspectives of the waste pickersâ?? cooperative networks. Ambient Soc. 2022.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Annual Report 2022. Urban cleaning service of the federal district.2022.

- Cruvinel VRN, Marques CP , Cardoso V , Novaes MRC , Araújo WN, et al. Health conditions and occupational risks in a novel group: Waste pickers in the largest open garbage dump in latin america. BMC Public Health. 2019; 19(1): 876-581.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Azevedo AMM, Gutberlet J, Araújo SD, Duarte FH. Impacts of COVID-19 on organized waste pickers in selected municipalities in the state of sao paulo. Ambiente and Sociedade. 2022; 25(2):106-112.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Women are 40% more likely to suffer from mental disorders. INPD-National Institute of Developmental Psychiatry for Children and Adolescents. 2021.

- Santos GO, Silva LFF. the meanings of garbage for garbage collectors in fortaleza (CE, Brazil). 2011;16(8):3413-3419.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Zolnikov TR, Silva RC, Tuesta AA, Marques CP, Cruvinel VRN. Ineffective waste site closures in brazil: A systematic review on continuing health conditions and occupational hazards of waste collectors. Waste Management. 2018; 80(8): 26-39.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Social determinants and health risks, non-communicable chronic diseases and mental health. brasilia. PAHO. Pan American Health Organization. WHO. Organization World Health. 2016.

- Goncalves DM, Stein AT, Kapczinski F. Performance of the self-reporting questionnaire as a psychiatric screening questionnaire: A comparativestudy with structured clinical interview for dsm-iv-tr. Public Health Notebooks. 2008; 24(2): 380-390.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Lira MVA, Santos SCA, Vidal PC, Costa CFT, Pereira MD. Mental suffering and academic performance in psychology students at sergipe. Research Society and Development. 2021; 10(10): 169-172.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- General technical and legal guidelines for selective collection and sorting services for recyclable materials, during the COVID-19 pandemic situation. National Council of the Public Prosecution Office. 2020.

- Cid MFB, Matsukura TS. Mothers with mental disorders and their children: risk and development. O Mundo Da Saude. 2010; 35(1): 73-81.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Santos CMB, Pereira RS, Fernandes FDS. Working conditions of solid waste collectors in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. Management and Connections Magazine. 2022; 11(3): 186-190.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn AV, Henrique HS. The improper disposal of face protection masks in the environment in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. Proceedings of The National Postgraduate Meeting 2021; 5(1): 1-5.

- Areias MEQ, Comandule AQ. Quality of life, work stress and burnout syndrome. Member of The Mental Health Laboratory. 2022.

[Google Scholar]

- Cruz SAFS. Why has sugarcane work been grinding people and spreading bagasse?. Katalysis Magazine. 2020; 23(3): 9-12.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Centenaro APFC, Beck CLC, Silva RM. Andrade A, Costa MC. Recyclable waste pickers: life and work in light of the social determinants of health. Brazilian Journal of Nursing. 2021; 74(6): 986-902.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Costa BL, Silva MA. Inequality for non-conformists: dimensions and confrontations of inequalities in brazil. Porto Alegre: CEGOV. 2020.

[Google Scholar]

- Matijascic M. Silva TD. Social situation of the black population by state. Brazil Institute of Applied Economic Research Ipea. 2014.

[Google Scholar]

- Social inequalities by colour or race in brazil. studies and research. IBGEâ?? Brazilian institute of Geography and Statistics. 2019.

- Silva TD, Silva SP, Trabalho. Diest_Trabalho Black Population And Pandemic. Brasilia: Ipea, 2020. Technical Note 46.

[Google Scholar]

- Andrade CB, CasuloAC, Alves G. Precarious work and mental health: Brazil in the neoliberal era. Cienc Public Health. 2019; 24 (12): 13-96.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Marques ES, Moraes CL, Hasselmann MH, Deslandes SF, Reichenheim ME. Violence against women, children and adolescents in times of the COVID-19 pandemic: Panorama, motivations and ways of coping. Public Health Notebooks. 2020; 36(4): 156-158.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa IC, Melo RLP, Medeiros MUF, Vasconcelos tm profile of psychological well-being in urban cleaning professionals. Journal Psychology Organizations and Work. 2010; 10(2): 54-66.

[Google Scholar]

- Vieira PR, Garcia LP, Maciel ELN. Social isolation and the rise of domestic violence: what does this tell us?. Brazilian Journal of Epidemiology. 2020; 23(1): 4-9.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Santos JE, Dutra ABM, Cruvinel VRN, Souza RC, Sander YCS, et al. Domestic violence and psychological distress: narratives of women waste pickers. Magazine uninga Review. 2021; 36(1): 40-53.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Loures DL, Santâ??Anna I, Baldotto CSR, Sousa EB, Nobrega ACL. Mental stress and the cardiovascular system. Brazilian Archives of Cardiology. 2002; 78(5): 11-15.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha KTB. COVID-19 pandemic and the effects caused on the mental health of essential workers. Multivix 2022; 21(3): 50-56.

[Google Scholar]

- Barros MBA, Lima MG, Malta DC, Szwarcwald CL, Azevedo RCS, et al. Report of sadness/depression, nervousness/anxiety and sleep problems in the brazilian adult population during the COVID-19 pandemic. Epidemiology and Health Services. 2020; 29(4): 20-25.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar]

) SRQ20 ≥ 7 No ;(

) SRQ20 ≥ 7 No ;( ) SRQ20 ≥ 7 Yes.

) SRQ20 ≥ 7 Yes.