Introduction

Substance use is a common condition and often

presents with psychotic symptoms. In fact, 7%-

25% of first episode psychosis is precipitated

by substance use [1]. Conversion rates from

Substance-Induced Psychotic Disorders (SIPD) to a Primary Psychotic Disorder (PPD) such as

schizophrenia vary with type of substance used.

Rates are highest (34%-50%) among cannabisinduced

psychotic disorder and lowest (5%)

among alcohol-induced psychotic disorder

[2-6]. Methamphetamine use can induce a

psychotic state known as Amphetamine-Induced Psychotic Disorder (AIPD) as defined by the

Diagnostic criteria in the fifth edition (DSM-5)

of the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental

disorders. There are an estimated 27 million

amphetamine users worldwide and approximately

2.3% of the North American population between

the ages of 15-64 have used amphetamines in the

past year [7]. It is estimated that as many as 40%

of amphetamine users experience AIPD [2].

Established risk factors for AIPD include a history

of a PPD, schizotypal and antisocial personality

disorders, family history of mental illness, and

methamphetamine dependence [8]. Conversion

rates from AIPD to a primary psychotic disorder

are in the range of 19%-40% [2,3,6,9,10]. There

are many Subjects (or is it Subjects-level) factors

that contribute in conversion from a SIPD to a

PPD (schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder)

including a family history of schizophrenia in a

first degree relative, male gender, subjects living

in urban areas, an extended duration of untreated

psychosis, continued substance abuse after index

psychotic episode, younger age at the time of the

first episode of substance induced psychosis, and

having a preexisting diagnosis of either a substance

use disorder, personality disorder (specifically

schizotypal and antisocial), or an eating disorder

prior to the index psychotic episode [2,6,11].

Moreover, conversions may occur rapidly. In one

study, it has been shown that 50% of conversions

from SIPD to schizophrenia occur within 3.1 years

of the index substance induced psychotic episode

[6].

Treatment of Substance Use Psychotic Disorders

(SIPD) is evolving [12]. It is a recent diagnostic

addition in the DSM-IV and has fallen under

significant scrutiny [13]. Subjects presenting

psychotic in the context of substance abuse are

often diagnosed with AIPD and providers may

neglect to consider the presence of an underlying

primary psychotic disorder. Confirmation bias is

an issue may delay in antipsychotic treatment or

inaccurate Subjects advice that the symptoms will

resolve with cessation of drugs alone. This may

lead to suboptimal treatment of Subjects with SIPD

[12]. Additionally, the SIPD Subjects population

is often excluded from clinical trials resulting in

a paucity of data to guide clinicians for subjects’

management [14,15]. This is alarming because

AIPD Subjects suffer from severe symptoms,

higher rates of hospitalization, and are more likely

to attempt suicide than methamphetamine users

without psychotic features [16]. Furthermore, younger AIPD Subjects with an average age of

30.4 years and a history of requiring hospitalization

have unusually high mortality rates (>8%) within

6 years of hospitalization [9]. This is of particular

concern within the veteran population given

that the suicide rate is higher among veterans as

compared to the general population and suicide

rate is doubled among veterans with a diagnosis

of a substance use disorder [17,18]. Despite

alarmingly high rates of mortality within the AIPD

subjects population, treatment is often delayed

resulting in prolonged periods of psychosis and

a poor prognosis [5]. To date there are only few

studies conducted in the in the veteran population.

Given the elevated risk of suicide within the

veteran population this study was undertaken to

understand the demographic profile, incidence

of mental disorders, substance use trends and

associated psychotic disorders among subjects

with mental illness admitted to a National VA

Medical Center (VAMC).

Materials and Methods

Data base and study design

Veterans’ Health Administration’s Corporate Data

Warehouse (VHA-CDW) uses a unique identifier

to identify veterans across treatment episodes at

more than 1,400 VHA centers organized under 21

Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs).

The VHA-CDW database contains veteran

health care information comprised of diagnostic,

laboratory, pharmacy, and other procedure related

data from various sources in the electronic health

record. VHA-CDW data and the VA Informatics

and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI) workspace

have been used widely for numerous studies of

clinical importance. Since we used VHA-CDW

and VINCI to extract data, consent has not been

necessary for this retrospective cohort study [19].

Study population

Mental health conditions, a composite measure

that included Psychosis, Manic-bipolar disorders,

PTSD, schizophrenia, depression and TBI all

defined by ICD-9 and ICD-10 according to

International Statistical Classification of Diseases

and Related Health Problems, Ninth and Tenth

Revision (ICD-9, ICD-10) codes, between

October 1, 1999, and February 27, 2022. The

study population consisted of 156,435 veterans

with MHC diagnosis (Group 2). We randomly

selected a total of 156,189 cases of admissions of similar gender, race, and age without any MHC

diagnosis (Group 1) during that period, balanced

for confounding factors such as age, race, sex,

smoking and Type 2 diabetes. The final study

groups comprise cases admitted to hospital with

and without various mental illnesses.

Data analysis

We used the date of first admission (first

occurrence in the data set) in the sample period

10/1/1999 through 02/27/2022 as the index time

point to differentiate pre-existing and new events

data and used a combination of standard SQL

accessible files such as ICD, lab, or drugs and free

text medical and administrative record searches

to collect information on conditions, medications,

and procedures.

Data were mainly used as categorical variables

and was analyzed by standard frequency tables

(chi sq and Odds ratios) using SAS (Guide 8.2)

was used for statistical analysis. Continuous

variables such as age are shown as Means (±

SD). Odds ratios (OR) were also calculated. A

Logistics procedure was used to initially evaluate

associations of multiple variables with the various

outcome variables. A greedy neighbor (nearest

neighbor) procedure was used as given by SAS

for the evaluation of all-cause mortality (death).

Principal outcomes were designated as number

of hospital admissions (1-9 or >10), suicide rate

(attempts/demise) and all-cause mortality among

two groups. Frequencies, means, and Odds ratios were calculated and are reported in the tables and

a p-value of <0.01 was deemed significant.

Ethics approval

This study (IRBNet #1663414) was approved

by the Kansas City VA Medical Center (FWA

00001481) Institutional Review Board (IORG

0000081) on March 17, 2022, and complies with

the declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Demographic characteristics of study population

We categorized principal demographics age groups (18-25, 26-35, 36-50, 51-65 and >65 years), race (American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, white, White Not of Hispanic origin and declined to answer/ unknown), ethnicity (Hispanic/Latino, non- Hispanic/Latino and unknown/declined to answer) and marital status (single/never married, married, separated/divorced, widow/widower/widowed and unknown/missing).

As shown in Table 1, age had a measurable effect on prevalence of mental illness. The proportion of subjects with a diagnosis of mental illness increased up to the 50 years and declined in >50 years old subjects. Age groups (18-25, 26-35, 36- 50, 51-65 and >65 years) are shown. In general, older subjects did better (OR=0.81, p<0.001).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of study population

| |

Group 1, subjects with

no Mental Health Conditions (MHC) diagnosis

N=156,189 |

Group 2 subjects with

MHC diagnosis

N=156,435 |

p-value Group 2 vs Group 1 |

| AGE groups, number (%) |

| 18-25 years |

125 (0.08%) |

172 (0.11%) |

- |

| 26-35 years |

6,388 (4.09%) |

9,730 (6.22%) |

- |

| 36-50 years |

24,537 (15.71%) |

33,555 (21.45%) |

- |

| 51-65 years |

80,422 (51.49%) |

74,760 (47.79%) |

- |

| Above 65 years |

44,701 (28.62%) |

38,201 (24.42%) |

- |

| ≥ 50 years |

44707 (28.62%) |

38,178 (24.42%) |

- |

| <50 years |

111,483 (71.38%) |

118257 (75.58%) |

<0.001 |

| Gender (sex), number (%) |

| Male |

147,769 (94.61%) |

146572 (93.7%) |

|

| Female |

8,421 (5.39%) |

9,855 (6.3%) |

<0.001 |

| Race characteristics-number (%) |

| American Indian/Alaska native |

1327 (0.85%) |

1455 (0.93%) |

- |

| Asian |

500 (0.32%) |

720 (0.46%) |

- |

| Black/African American |

63,788 (40.84%) |

62,089 (39.69%) |

- |

| Native Hawaiian/other pacific islanders |

984 (0.63%) |

1001 (0.64%) |

- |

| White |

82,218 (52.64%) |

84006 (53.7%) |

- |

| White not of Hispanic origin |

594 (0.38%) |

469 (0.3%) |

- |

| Unknown or declined to answer |

6,779 (4.34%) |

6695 (4.28%) |

- |

| White |

80,037 (51.24%) |

83,431 (53.33%) |

<0.001 |

| Others |

76,153 (48.76%) |

73,012 (46.67%) |

|

| Ethnicity characteristics, number (%) |

| Not Hispanic/Latino |

144,209 (92.33%) |

143482 (91.72%) |

- |

| Hispanic/Latino |

7403 (4.74%) |

9057 (5.79%) |

<0.001 |

| Unknown or declined to answer |

4576 (2.93%) |

3614 (2.31%) |

- |

| Marital status, number (%) |

| Single/never married |

38,204 (24.46%) |

41,721 (26.67%) |

- |

| Married |

28,176 (18.04%) |

27157 (17.36%) |

- |

| Separated/divorced |

83,483 (53.45%) |

81,925 (52.37%) |

- |

| Widow/widower/widowed |

5592 (3.58%) |

5350 (3.42%) |

- |

| Unknown/missing |

734 (0.47%) |

282 (0.18%) |

- |

| All-cause mortality, number (10%) |

| Alive |

1,02,380 |

1,12,023 |

<0.001 |

| Dead |

53,810 |

44,412 |

- |

|

Note: Numbers (%); Total subjects (percent).

|

Males were less frequently associated with mental diagnosis than females (OR=0.85, p<0.001). There was a difference in the prevalence of mental illness based on race (White vs other OR=0.92 p<0.001). Race and ethnicity were grouped (American Indian or Alaska native, Asian, black, or African American, native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, white, white not of Hispanic origin and declined to answer/unknown), ethnicity (Hispanic/Latino, Non-Hispanic/Latino and unknown/declined to answer) of interest, Hispanic were more likely to carry a diagnosis of mental illness (OR=1.28, p<0.001).

Marital status was examined (single/never married, married, separated/divorced, widow/widower/widowed and unknown/missing). A great majority of subjects in the study were divorced or separated. About 18% were married and about 25% had never been married of interest, death during study period was less common (OR=0.740, p<0.001) in mental illness group compared to control group.

Distribution of various MHC diagnoses

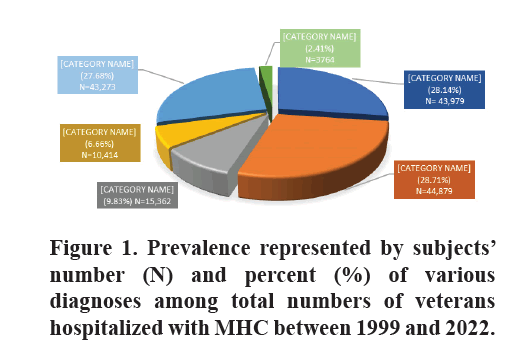

As shown in Figure 1, psychosis, manic-bipolar and PTSD were most common diagnosis at 28% each followed by schizophrenia (9.83%) and depression (6.66%). TBI was uncommon at 2.4% of cases. Our analysis did not exclude any cases from any category where there was overlap as the primary condition could not always be identified.

Frequency and types of substances used

Overall drugs use was very frequent in Group 2-MHC diagnosis (OR 11.1). There were notable differences for the types of drugs used. Barbiturates (OR 4.9), PCP (OR 5.0), and Cocaine (OR 5.2) use increased to a similar degree. Amphetamines (OR 9.4), Cannabis (OR 10.5) and Codeine (OR 13.9) were all increased even more strongly and a monumental increase in use of Morphine (OR 38.6) and Fentanyl (OR 57.9) was found in subjects with MHC.

As shown in Table 2, subjects with MHC diagnosis (Group 2) were significantly associated with an overall increase in substance use as compared to Group 1-no-MHC (11.98% vs 1.37%). The most abused substance was amphetamines (2.67% vs 0.29%) followed by cannabis (2.3% vs 0.23%), codeine, morphine, and cocaine. These were all at least two times as common as barbiturates or fentanyl. PCP use was uncommon among these subjects.

Table 2. Substances use frequency among subjects with and without Mental Health Conditions (MHC) diagnosis.

| |

Group 1 no MHC 156189 |

Group 2 MHC 156435 |

Odds ratio Group 2 vs Group 1 |

p-value Group 2 vs Group 1 |

| Drug users N (%) |

2134 (1.37%) |

18,744 (11.98%) |

11.1 |

<0.0001 |

| Amphetamine |

453 (0.29%) |

4179 (2.67%) |

9.4 |

<0.0001 |

| Barbiturates |

406 (0.26%) |

1927 (1.23%) |

4.9 |

<0.0001 |

| Cannabis |

359 (0.23%) |

3617 (2.31%) |

10.5 |

<0.0001 |

| Cocaine |

513 (0.33%) |

2650 (1.69%) |

5.2 |

<0.0001 |

| Codeine |

222 (0.14%) |

3051 (1.95%) |

13.9 |

<0.0001 |

| Fentanyl |

13 (0.01%) |

750 (0.48%) |

57.5 |

<0.0001 |

| Morphine |

52 (0.03%) |

1987 (1.27%) |

38.6 |

<0.0001 |

| PCP |

116 (0.07%) |

583 (0.37%) |

5 |

<0.0001 |

|

Note: Numbers as (percent) of total subjects in Group1 (control) and Group 2 (MHC); p-value represents significance when compared Group 2 vs Group 1.

|

Primary and drug-induced psychosis among veterans with mental health conditions

As shown in Table 3, about 28% (N=43,979) of 156,435 subjects with mental illness in this study carried a psychosis diagnosis of which majority were non-substance users (88.1%, N=38,710). Among 11.9% substance users (N=5269) with psychosis, only 1,174 subjects used amphetamine resulting in an Amphetamine Induced Psychotic Disorder (AIPD) rate of 22.28%. Psychosis among other substance users including cannabis, codeine, morphine, cocaine, barbiturates, fentanyl, and PCP persisted in 4,095 subjects resulting in Substance abuse related Psychosis Disorder (SIPD) rate of 77.72%.

Table 3. Amphetamine-Induced Psychosis Disorder (AIPD) vs other Substances-Induced Psychosis Disorder (SIPD) among subjects diagnosed with psychosis.

| Total veterans with MHC N=156,435 |

| Veterans with Psychosis DX N=43,979 (28.14%) |

| Substance users, N=5,269 (11.98%) |

Non-substance users N=38,710 (88.01%) |

| Amphetamine users, N= 1,174 |

Other substance users N=4095 |

| AIPD rate 22.28% |

SIPD rate 77.72% |

|

Note: Numbers as (percent) of total subjects in the category; AIPD and SIPD rate in % is calculated by dividing numbers of amphetamine and other substances users by the number of substance users with psychosis diagnosis.

|

Frequency of hospitalization, suicide attempts and suicide death

Principle outcome examined included >10 hospitalization, suicide, attempts and suicide death. As shown in Table 4, frequency of hospitalization (>10 admissions) was significantly higher (p-value <0.001) in population with mental illness, Group 2 (52.95%) as compared to no mental illness Group 1 (47.11%) with an OR=1.22. Similarly, rate of suicide rate, attempts and death was also significantly higher (p<0.0001) in mental illness Group 2 as compared to no mental illness Group 1.

Table 4. Comparison of outcomes among subjects with and without MHC

| Measured outcome |

Group 1 control (no-MHC)

156,189 |

Group 2 MHC diagnosis

156,435 |

Odds ratio Group 2 vs Group 1 |

p-value Group 2 vs

group 1 |

| >10 admissions |

73,581 (47.11%) |

81,419 (52.05%) |

1.22 |

<0.0001 |

| Suicide |

3,972 (2.54%) |

58,012 (37.08%) |

23.32 |

<0.0001 |

| Attempt |

2,644 (1.69%) |

43,035 (27.51%) |

57.5 |

<0.0001 |

| Suicide |

1,328 (0.85%) |

14,698 (9.40%) |

38.6 |

<0.0001 |

|

Note: Numbers as (percent) of total subjects in Group 1 (control) and Group 2 (MHC); p-value represents significance when compared Group 2 vs Group 1.

|

Discussion

Demographic characteristics of our study

population demonstrated that mental illness

diagnosis was less frequently associated with

males than females (OR=0.85, p<0.001). These

findings parallel global statistics. The agestandardized

disability-adjusted life-years rate for

mental disorders, prevalence and incidence rates

of common mental disorders, specifically affective

disorders, such as anxiety and depression, is greater

in females than males [20,21]. We found that

overall mortality was less common (OR=0.740,

p<0.001) in mental illness group compared to

control group. This correlates with the findings

of the systematic analysis for the Global Burden

of Disease Study 2019, which concluded that

estimated years of life lost for mental disorders

were low and do not reflect premature mortality

in individuals with mental illness [20]. Veterans

of Hispanic origins were more likely to carry a

diagnosis of mental illness (OR=1.28, p<0.001).

Our data and published reports suggest a need to

do additional epigenetic and sociocultural research

in the Hispanic population [22].

We found that substance abuse was significantly

higher in the mental illness group (11.98%)

compared to the control group (1.37%, (OR=11.1).

Co-occurring Substance Use Disorders (SUD) with

Mental Disorders is a well-known phenomenon,

frequently referred as a dual diagnosis, which is

highly prevalent and represents a serious national

health problem. Unfortunately, it is often underdiagnosed

and therefore, poorly treated. In a

nationally representative U.S sample, dually

diagnosed adults are estimated to represent 17.8%

of the 75.6 million adults diagnosed with SUD and

Mental disorder [23].

We observed a monumental increase in abuse of

morphine (OR=38.6) and fentanyl (OR-57.9) by

48 and 42 times, respectively, among subjects with

mental illness when compared with hospitalized

adults without concurring mental illness. It is well

known that a dual diagnosis is especially prevalent

among adults with the Opioid Use Disorder

(OUD) and that it increases the risk for morbidity

and mortality. For instance, 24.5% of adults with

OUD and recent mental illness in the past year

and 29.6% of adults with OUD and serious mental illness reported receiving services for both mental

health and substance use treatment [24]. This

is alarming because opioid abuse in the US has

reached an epidemic status. The alarming increase

in fentanyl abuse found in our study corresponds

with the current course of the US opioid crisis.

Three main causes for the opioid epidemic are:

• Increase in prescription of opioids,

• Drug use, and

• Access to illicitly manufactured fentanyl.

Centers for disease control and prevention

statistics estimated 500,000 opioid associated

deaths between 1996 and 2019.

While death related to the opioid drug overdose

started to decline in 2017, Fentanyl use associate

deaths continue to increase [25].

Use of amphetamine among veterans with mental

illness is higher than estimated use among 15-64

years old North American population. We detected

that amphetamines (OR=9.4), cannabis (OR=10.5)

and codeine (OR=13.9) abuse was 9.2 to 13.92

times more frequently noted in the MHC group.

Moreover, amphetamine was the most frequently

used substance (2.67%), followed by cannabis

(2.3%), codeine, morphine, cocaine, barbiturates,

fentanyl, and PCP in the mental illness group. Our

findings correlate with both nation and worldwide

trends, showing that synthetic drugs, represented

by methamphetamine, have become the most

abused drugs in the world and have surpassed

traditional drugs of abuse (including opioids).

The rates of stimulant use disorders, including

methamphetamine, and stimulant-related overdose

and mortality is steadily increasing in the USA

[26-29].

We observed that Amphetamine Induced Psychotic

Disorder (AIPD) presented in 22.28% whereas

other Substance (cannabis, codeine, morphine,

cocaine, barbiturates, fentanyl, and PCP) Induced

Psychotic Disorder (SIPD) presented in 77.72%.

Psychosis has been described in the medical

literature as a well-known complication of longterm

methamphetamine use since after the Word

War II. Epidemiologic studies provide different

opinions regarding the prevalence of AIPD [30].

One meta-analysis of seventeen studies showed a

composite event rate of 36.5%. Overall, difference

in prevalence of AIPD varies from 13% in the

USA to 50% in Asia that can be explained by the

potency and purity of methamphetamines used in different geographic locations [31].

The time elapsed from the initial substance use to

developing AIPD varies from a few weeks to years.

It is influenced by the frequency of consumption,

dose of the substance, route of administration

(intravenous, oral, inhalation), and individual

vulnerability to psychosis. Early consumption of

amphetamines initially induces psychotomimetic

effects, to include euphoria, feelings of increased

concentration and stimulation. Continuous use

of methamphetamines induces pre-psychotic

delusional moods followed by overt psychotic

state manifesting with delusions and hallucinations

[32].

In our study 11.98% of veteran-subjects with

psychosis diagnosis used substance. Psychosis

among amphetamine and other substance users

presented at higher rate among subjects with mental

illness. The most prevalent AIPD symptoms are

persecutory delusion (82%), auditory hallucination

(70.3%), and delusion of reference (57.7%),

visual hallucination (44.1%), grandiosity delusion

(39.6%) and jealousy delusion (26.1%). AIPD

may be accompanied by severe violent behavior

warranting clinical intervention to prevent harm

to subjects and society. Tactile hallucinations are

more so frequent among subjects using higher

daily doses of the drug and frequently described

as parasites crawling under subject’s skin

(formication, “meth mites”).

Chronic methamphetamine use induces

neuroinflammation, ischemia, oxidative stress,

and direct neurotoxicity leading to degeneration

processes. It may unmask or expedite the

development of schizophrenia in first-degree

relatives of subjects with schizophrenia,

emphasizing the importance of differentiating

AIPD from schizophrenia. Higher prevalence

of visual and tactile hallucinations was reported

among subjects with AIPD vs schizophrenia,

while delusion patterns were similar in both

groups. Subjects with AIPD have less “negative”

psychotic symptoms (i.e., social withdrawal,

blunted affect, disorganization, etc.,) and similar

levels of “positive” symptoms (i.e., hallucinations,

paranoid delusions) compared with schizophrenic

subjects [32,33].

The large number of drug reactions and side

effects would be expected to lead to increased

use of medical services and complications.

Indeed, we found that a diagnosis of mental

illness was significantly associated with higher(>10) admission rates (OR=1.22), suicide rate

(OR=23.3), suicide attempts (OR=57.5), and

suicide death (OR=38.6). Suicide is more prevalent

among veterans compared with the general US

population. Data published by the US department

of Veterans affairs in 2016 showed that veteran

suicide rates were 1.5 times higher than among

non-veterans. Our data coincide with the findings

that mental illness significantly increases the risk

of suicide in veterans, in addition to other risk

factors, such as older age, male gender, substantial

medical comorbidities, substance abuse etc., [34-36]. Female veterans with substance use disorders

are at particularly elevated risk for suicide [37].

Moreover, approximately 30% of completed

suicides and 20% of deaths resulting from high risk

behavior were attributed to substance use,

according to the study conducted on military

personnel [38,39].

Both suicide rates (37.08%) and substance use

(11.98%) were significantly higher in the mental

illness group compared to control group (2.54%

and 1.37% correspondingly). Substance use has

been identified as a strong risk factor for suicidal

behavior among US Veterans [38]. Amphetamine

was the most used substance followed by

cannabis in the studied mental illness group.

The incidence of overdose-induced deaths due

to psycho-stimulants other than cocaine (largely

methamphetamine) is on significant rise. Cannabis

use has also been indicated as a risk factor for

suicide in veterans. Logistic regression models

indicated that cannabis use was associated with

past year suicidal ideation and elevated risk for

suicidal behavior. These findings included a

concerning association between cannabis use and

suicide risk in Gulf War veterans [40].

Increasingly common use of stimulants with

synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl and its

analogies and surge in amphetamine use and

AIPD among veterans with mental illness in

the light of documented high rates of mortality

associated with amphetamine use and substanceinduced

psychosis is underestimated and warrants

immediate attention to this mental health

emergency. Keeping in mind the deadly risks

associated with it, methamphetamine has become

“America’s most dangerous drug”. Stimulantrelated

deaths involving psycho-stimulants other

than cocaine (largely methamphetamine) are on

the rise in the United States. Psycho-stimulantrelated

mortality has progressively increased

5-fold from 2012 to 2018 [29,36].

Unfortunately, there are no FDA-approved

medications for treating either AIPD or

methamphetamine use disorder. Most medications

evaluated for methamphetamine/amphetamine use

disorder have not shown a statistically significant

benefit. However, there is low-strength evidence

that Methylphenidate may reduce amphetamine/

methamphetamine use.

Numerous Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs)

investigated over 20 potential pharmacotherapies.

Methylphenidate, Bupropion, Modafinil, and

Naltrexone demonstrated limited evidence

of benefit for reducing amphetamine use.

Dexamphetamine has benefit on treatment

retention, but not for reducing amphetamine

use. Based on moderate strength evidence,

antidepressants as a class, to include SSRIs, have

not shown statistically significant effect on either

abstinence or treatment retention [41,42].

Methamphetamine triggers neurotoxicity,

oxidative change, neuroinflammation, induces

cell death cascade, and degenerative loss of

dopaminergic neurons in the brain, which

contributes to the higher risks of developing

Parkinsonism syndrome and Parkinson’s disease

itself among methamphetamine users [43].

Therefore, when treating AIPD, clinicians should

keep in mind that these subjects are at increased

risks of extrapyramidal movement complications,

if treated with the first-generation antipsychotics,

such as Haloperidol. Consequently, secondgeneration

antipsychotics maybe a preferable class

to address psychotic symptoms of AIPD. Subjects

diagnosed with substance induced psychotic

disorder require close follow up and treatment

with psychotropic medications.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our results call for action to increase awareness among VHAs and general practicing clinicians to address the surge in amphetamine use and related mortality, seek evidence-based prevention strategies, and treatment interventions for the amphetamine use associated disorder including AIPD. Further research is urgently needed to identify successful public health approaches targeting Methamphetamine abuse epidemic and to develop effective clinical interventions and relapse prevention strategies.

Our findings underscore the importance of considering demographic factors such as age, gender, race, and service-related characteristics in understanding the complex landscape of mental health among veterans. Furthermore, the link between substance use and psychotic disorders among this population highlights the need for integrated screening, prevention, and treatment approaches that address both mental health and substance use disorders concurrently.

Limitations of our study include

• False-positive or false-negative Urine Drug Screens (UDS) for amphetamine might have occurred in small number of subjects.

• UDS amphetamines detection could have included prescription stimulants for ADHD, narcolepsy, off-label treatment for major depressive disorder, weight-loss medication, etc., and

• Initial diagnosis of AIPD could have overlapped with unmasked symptoms of first onset of psychosis, schizophrenia, or schizophrenia-like presentation secondary to poly substance use, including highly potent synthetic cannabinoids.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the resources from

both Kansas City VA medical center and Midwest

Veterans biomedical research foundation.

Disclosures

The contents of this article are those of authors and

do not necessarily reflect the position and policy

of the Department of Veterans Affairs. All authors’

participants have given consent for their data to

be used in the research. The data that support

the findings of this study are available from the

corresponding author, (RS), upon reasonable

request.

References

- Regier DA, Kuhl EA, Kupfer DJ. The DSM‐5: Classification and criteria changes. World Psychiatry. 2013;12(2):92-98. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Murrie B, Lappin J, Large M, Sara G. Transition of substance-induced, brief, and atypical psychoses to schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2020;46(3):505-516. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Niemi-Pynttäri JA, Sund R, Putkonen H, Vorma H, Wahlbeck K, et al. Substance-induced psychoses converting into schizophrenia: A register-based study of 18,478 Finnish inpatient cases. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(1):20155. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Shah D, Chand P, Bandawar M, Benegal V, Murthy P. Cannabis induced psychosis and subsequent psychiatric disorders. Asian J Psychiatr. 2017;30:180-184. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Jeppesen P, Petersen L, Thorup A, Abel MB, Øhlenschlaeger J, et al. The association between pre-morbid adjustment, duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in first-episode psychosis. Psychol Med. 2008;38(8):1157-1166. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Starzer MS, Nordentoft M, Hjorthøj C. Rates and predictors of conversion to schizophrenia or bipolar disorder following substance-induced psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(4):343-350. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Substance abuse and mental health services administration. 2021.

- Glasner-Edwards S, Mooney LJ. Methamphetamine psychosis: Epidemiology and management. CNS Drugs. 2014;28:1115-1126. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Kittirattanapaiboon P, Mahatnirunkul S, Booncharoen H, Thummawomg P, Dumrongchai U, et al. Long‐term outcomes in methamphetamine psychosis patients after first hospitalisation. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010;29(4):456-461. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Alderson HL, Semple DM, Blayney C, Queirazza F, Chekuri V, et al. Risk of transition to schizophrenia following first admission with substance-induced psychotic disorder: A population-based longitudinal cohort study. Psychol Med. 2017;47(14):2548-2555. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Björkenstam E, Björkenstam C, Hjern A, Reutfors J, Bodén R. A five year diagnostic follow-up of 1840 patients after a first episode non-schizophrenia and non-affective psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2013;150(1):205-210. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, Van Weeghel J, Garretsen HF. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: Systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1-2):23-35. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Mathias S, Lubman DI, Hides L. Substance-induced psychosis: A diagnostic conundrum. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(3):358-367. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Weibell MA, ten Velden Hegelstad W, Johannessen JO. Substance-induced psychosis: Conceptual and diagnostic challenges in clinical practice. InNeuropathology of Drug Addictions and Substance Misuse 2016:50-57. [Google Scholar]

- Fusar-Poli P, Cappucciati M, Bonoldi I, Hui LC, Rutigliano G, et al. Prognosis of brief psychotic episodes: A meta-analysis. JAMA psychiatry. 2016 Mar 1;73(3):211-20. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Glasner-Edwards S, Mooney LJ, Marinelli-Casey P, Hillhouse M, Ang A, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of methamphetamine-dependent adults with psychosis. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;35(4):445-450. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Blow FC, Bohnert AS, Ilgen MA, Ignacio R, McCarthy JF, et al. Suicide mortality among patients treated by the veterans health administration from 2000 to 2007. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(S1):S98-104. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Ilgen MA, Bohnert AS, Ignacio RV, McCarthy JF, Valenstein MM, et al. Psychiatric diagnoses and risk of suicide in veterans. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(11):1152-1158. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI). 2024.

- GBD. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(2):137-150. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Shimamoto A, Rappeneau V. Sex-dependent mental illnesses and mitochondria. Schizophr Res. 2017;187:38-46. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Alarcón RD, Parekh A, Wainberg ML, Duarte CS, Araya R, et al. Hispanic immigrants in the USA: Social and mental health perspectives. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(9):860-870. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Jegede O, Rhee TG, Stefanovics EA, Zhou B, Rosenheck RA. Rates and correlates of dual diagnosis among adults with psychiatric and substance use disorders in a nationally representative US sample. Psychiatry Res. 2022;315:114720. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Jones CM, McCance-Katz EF. Co-occurring substance use and mental disorders among adults with opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;197:78-82. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Gardner EA, McGrath SA, Dowling D, Bai D. The opioid crisis: Prevalence and markets of opioids. Forensic Sci Rev. 2022;34(1):43-70. [Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Courtney KE, Ray LA. Methamphetamine: An update on epidemiology, pharmacology, clinical phenomenology, and treatment literature. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;143:11-21. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Fogger SA. Methamphetamine use: A new wave in the opioid crisis? J Addict Nurs. 2019;30(3):219-223. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Ciccarone D, Shoptaw S. Understanding stimulant use and use disorders in a new era. Med Cli North Am. 2022;106(1):81-97. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Ciccarone D. The rise of illicit fentanyls, stimulants and the fourth wave of the opioid overdose crisis. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2021;34(4):344-350. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Lecomte T, Dumais A, Dugre JR, Potvin S. The prevalence of substance-induced psychotic disorder in methamphetamine misusers: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2018;268:189-192. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Ujike H, Sato M. Clinical features of sensitization to methamphetamine observed in patients with methamphetamine dependence and psychosis. Anna N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1025(1):279-287. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Fasihpour B, Molavi S, Shariat SV. Clinical features of inpatients with methamphetamine-induced psychosis. J Ment Health. 2013;22(4):341-349. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Edinoff AN, Kaufman SE, Green KM, Provenzano DA, Lawson J, et al. Methamphetamine use: A narrative review of adverse effects and related toxicities. Health Psychol Res. 2022;10(3). [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Inoue C, Shawler E, Jordan CH, Moore MJ, Jackson CA. Veteran and military mental health issues. 2023. [Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Barbic D, Whyte M, Sidhu G, Luongo A, Chakraborty TA, et al. One-year mortality of emergency department patients with substance-induced psychosis. PLoS One. 2022;17(6):e0270307. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Han B, Compton WM, Jones CM, Einstein EB, Volkow ND. Methamphetamine use, methamphetamine use disorder, and associated overdose deaths among US adults. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(12):1329-1342. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Chapman SL, Wu LT. Suicide and substance use among female veterans: A need for research. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2014;136:1-0. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Na PJ, Nichter B, Hill ML, Kim B, Norman SB, et al. Severity of substance use as an indicator of suicide risk among US military veterans. Addict Behav. 2021;122:107035. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Bohnert KM, Ilgen MA, Louzon S, McCarthy JF, Katz IR. Substance use disorders and the risk of suicide mortality among men and women in the US Veterans health administration. Addiction. 2017;112(7):1193-1201. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Grove JL, Kimbrel NA, Griffin SC, Halverson T, White MA, et al. Cannabis use and suicide risk among gulf war veterans. Death Stud. 2023;47(5):618-623. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Lee NK, Jenner L, Harney A, Cameron J. Pharmacotherapy for amphetamine dependence: A systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;191:309-37. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Chan B, Freeman M, Kondo K, Ayers C, Montgomery J, et al. Pharmacotherapy for methamphetamine/amphetamine use disorder-a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Addiction. 2019;114(12):2122-2136. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

- Jayanthi S, Daiwile AP, Cadet JL. Neurotoxicity of methamphetamine: Main effects and mechanisms. Expe Neurol. 2021;344:113795. [Crossref][Google Scholar][PubMed]

Citation: Demographic Profile, Substance use Trends and Associated Psychotic Disorders among Veterans with Mental Health

Conditions: A Retrospective Cohort Study of Us Veterans ASEAN Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 25 (7) July, 2024; 1-11.